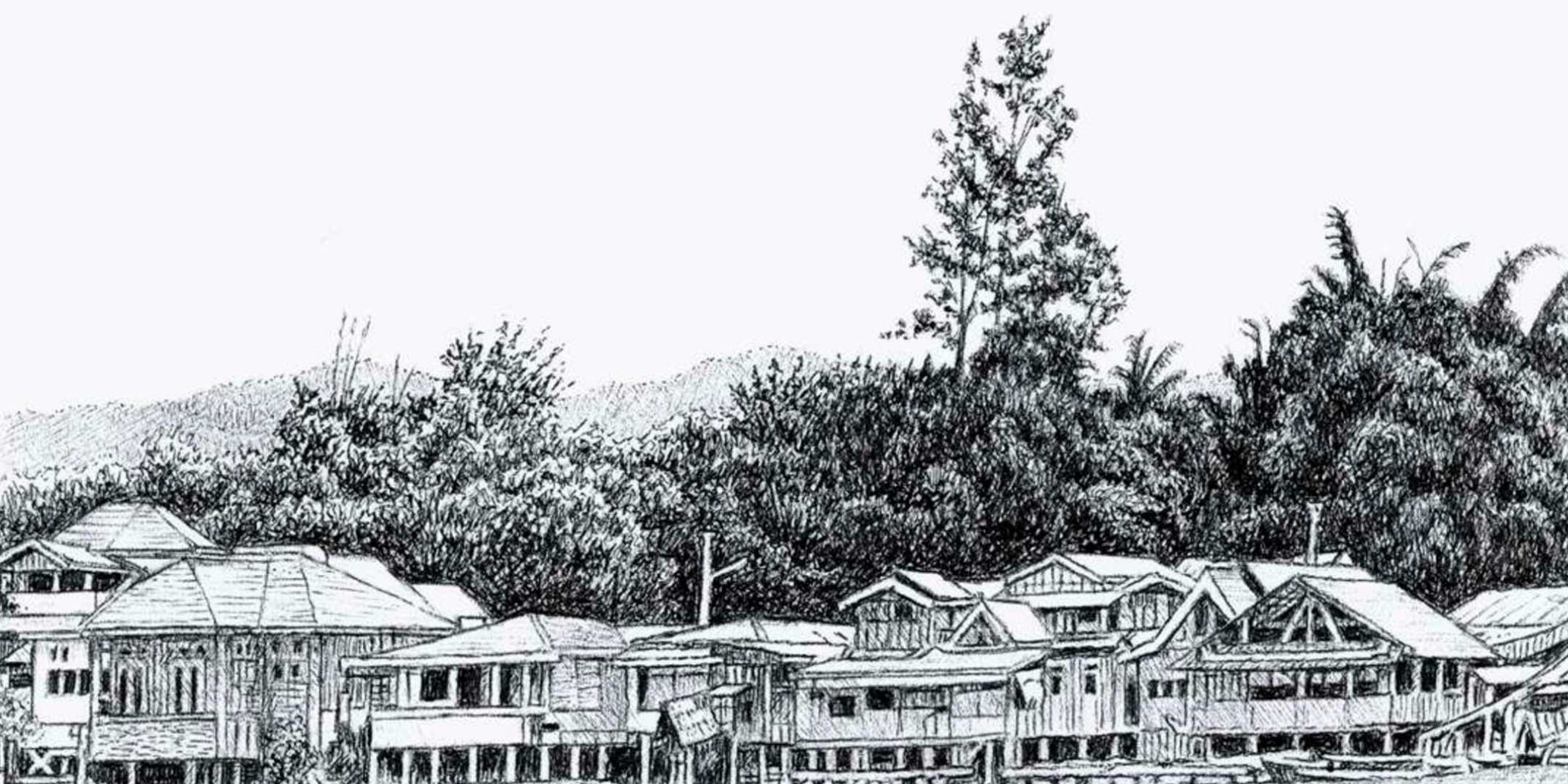

A glimpse of some traditional boats: Fifty-six days in Sulawesi, Indonesia, 2015

This visit began in Manado at the northern tip of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi and included a ferry journey from Gorontalo to Ampana via the Togean Islands, a week’s stay in Tentena on the shores of Lake Poso, three weeks in the Toraja highlands, a few days in Makassar and four days at Bira Beach on the southern tip of Sulawesi.

Throughout much of the journey I rendered many drawings directly from life and they include a number of studies of traditional boats. It’s these images that I wish to share along with these notes, visuals and maps about boatbuilding in Sulawesi, and its wider context.

Outrigger boats

Double outrigger canoes, common in South East Asia and parts of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, may possibly have been invented by Austronesian seafarers 5000 years ago. Austronesians spread from southern China through Taiwan and the islands and coasts of south-East Asia, becoming today’s Filipinos, Malays, Chams of Vietnam, Indonesians and more recently the inhabitants of Madagascar and Polynesia.

It’s even possible that early Austronesian mariners introduced the dingo into Australia, about 4000 years ago. Several centuries ago, Austronesian descendants known as Makassans began sailing regularly to northern Australia from Sulawesi on fishing and trading expeditions, and images of them and their boats are found in Aboriginal rock and bark paintings.

In Sulawesi, outrigger canoes are now known as lipa-lipa. In Java, Madura, Bali and Lombok, they are called jukung. Their designs vary according to their localities and specific requirements.

Originally outrigger canoes were single-log dugouts stabilised by bamboo floats attached to timber cross spars. This outrigger principal remains unchanged but hull designs often became more sophisticated, including construction with planks. The outriggers increased stability, facilitated greater speed and enabled sailors to paddle through rough water. The paddles are single-sided and, unlike kayaking or rowing, they are usually used on only one side of the craft. However, large outrigger ships such as the kora-kora of the Moluccas, encountered by European explorers, used both paddles and rowers pulling oars.

The sails of outrigger boats commonly take two forms: triangular, or tilted rectangles. Both types are set between upper and lower spars of flexible bamboo. In Sulawesi the tilted rectangular form is known known as tanja. In modern times, outboard engines are nearly always used on outrigger craft and sometimes replace sails altogether.

Tanja sail carried on a pajala hull. Image: Richard Gregory. After an illustration in Boats to Burn: Bajo Fishing Activity in the Australian Fishing Zone by Natasha Stacey. Sources: Hawkins 1982, Birmingham 1996.

The Bugis

The best-known specialist mariners of South-East Asia are the Bugis, the largest ethnic group of South Sulawesi, who inhabit its coasts and fertile, rice-growing lowlands. Their Austronesian ancestors established settlements in the region around 2500 BC, and by 1200 AD the Bugis had developed into competing kingdoms based on agriculture, fishing and maritime trade.

The Bugis were stimulated by trade with South-East Asia, China and India, and benefited from access to iron ore for the manufacture and lucrative trade of weapon blades and tools. Well before the European colonisation of South East Asia, Australia and New Guinea, Bugis sailors traded across the region as far as the Gulf of Carpentaria. Their earlier religions included forms of animism, Hinduism and Buddhism, while from 1605 they adopted Islam.

By the end of the 17th century, civil war and Dutch invasion led to a Bugis diaspora establishing settlements in Malaya, Sumatra, Borneo and Indonesia’s eastern islands (Nusa Tenggara). Their maritime activities included piracy and slave raiding, while due to their energetic and adventurous characteristics, the Bugis became prominent in regional affairs and politics. Today they are prominent as boat builders where forest timber is available, for example coastal Kalimantan.

Pinisi: The iconic Bugis boats

Pinisi are the big 20th-century sail traders that are synonymous with the Bugis and their closely related neighbours in South Sulawesi, the Makassans … fellow sailors and shipbuilders and rivals in trade and warfare.

Pinisi development was a combination of Indigenous and European influences. The term pinisi refers to the standing gaff-ketch sailing rig which evolved over the 19th and 20th centuries. Originally small craft of about 15 to 20 tonnes, the term now applies to modern timber motor-sailers of several hundred tonnes built in the Bugis and Makassan traditions.

Earlier Bugis vessel types called pajala, palari and padewakang were used for long distance voyages serving the south Sulawesi kingdoms. Indigenous, tilted rectangular tanja sails, featuring flexible bamboo poles fastened to the longer upper and lower edges of the sail, were the standard rigs. Tanja sails, an Austronesian invention, are first depicted in the Buddhist stupa Borobudur, 8th century CE, in central Java.

From the 16th to the 19th century Dutch and other western boat-building practices made an impact as square-rigged and gaff-rigged ships visited the archipelago. European fore-and-aft sails came to appear in various conjunctions with the tanja sail. This included the standing gaff rig which, by around 1900 started to develop into the pinisi rig.

The traditional hull form featured a rockered keel and curved stem and stern posts, and the distinctive and ancient Bugis-Makassan steering system of two side rudders fitted to both aft quarters. The rudder system is also recorded earlier in cave art approximately 2000 years old, and again in the 8th century CE, at Borobudur.

Traditional hull construction, continuing today, begins with joining the keel, stem and stern posts. A shell of hull planks is then built, edge-fastened together with internal wooden treenails called paku. The frames are added after the hull planks are assembled. This is a technique employed in the west for clinker hulls where the planks overlap each other. In Indonesia the planks are carvel, that is, placed edge to edge.

Motors were introduced to Indonesian sail-trading vessels from the 1970s. By the early 1980s the Bugis and Makassan sailing pinisi had all become auxiliary motor-sailers, doing away with the mizzen (aft) mast and reducing the size of the main mast and bowsprit, and the number of jibs. Over recent decades the pinisi hull shape has also evolved to suit this new means of propulsion by adopting straight, sharply angled bows and sterns, centre line rudders and overhanging counter sterns.

Today shipyards are still just beaches that are convenient for the landing of logs for construction. In the past, teak was favoured but it is now scarce and other harder timbers are preferred, such as ironwood from Kalimantan. Traditional carpentry skills remain a dominant characteristic despite the recent use of electric drills and chain saws: the work is all carried out by hand and without plans of any sort.

Construction of boats still retains rich cultural traditions that includes ceremonies performed at all the important stages of a boat’s construction.

— Richard Gregory, Illustrator.

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of ANMM Honorary Research Associate Jeffrey Mellefont in sharing his extensive knowledge of Indonesian boat building while discussing, correcting and editing the drafts of this text. Acknowledgement is also due to the very informative paper of Horst Liebner [name and date of paper needed] and its technical drawings.

Richard is a retired Visual Arts teacher and lecturer who has also spent a large part of his life as a freelance illustrator. His clients include publishers and museums. He specialises in historical subjects which he carefully researches and renders in fine detail.

Originally he is from the United Kingdom where he studied painting but since the mid-sixties he worked his way across Asia and settled in Australia. In the early seventies, he returned to travelling and after spending time in the far-east, settled in Canada for four years. It was there he concentrated on book illustration. Eventually, Richard returned to Sydney where he continued with his freelance work, but also committed himself to teaching.

Since his retirement he has studied traditional architecture in central and eastern Asia and occasionally takes a keen interest in maritime subjects. These areas are the basis of his frequent travels where he undertakes field work in the form of drawings executed directly from life.