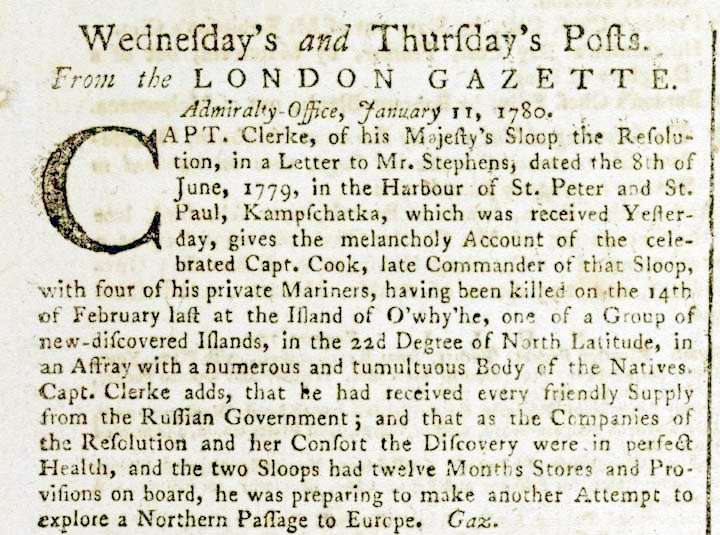

Death announcement of Captain Cook in the London Gazette, 18 January, 1780 (source – British Library)

When the news of Cook’s death reached London in 1780, it did not make front page news, but rather, was merely noted with a small announcement of a single paragraph. But public expressions of grief came, one being ‘Elegy on Captain Cook’ written by Anna Seward in 1780.

Seward was both unusual and yet typical for her time. As the eldest surviving daughter of the widowed canon of Lichfield, she had elected not to marry in order to care for her ailing father. But rather than see it as a hindrance to her social standing, Seward embraced her lifelong single status and became what her mother had once greatly feared she would, ‘a literary lady’.

Supported by a generous allowance, Seward lived all her life at Lichfield and found herself part of a literary and intellectual community that in hindsight, was quite extraordinary. She became a close friend of Erasmus Darwin and Dr Samuel Johnson, a correspondent of Sir Walter Scott and associated with the Lunar Society whose members included Josiah Wedgewood.

Despite this discerning circle, Seward’s poetry did not receive wider attention until 1780 when, at the news of Cook’s death, she wrote her ‘Elegy on Captain Cook’ and submitted for competition at Lady Millers Poetical Amusements. Although Miller’s poetry contest was derided in intellectual circles, it was well intended, extremely popular and by winning it, Seward drew attention from publishers and found some measure of fame and praise. She became referred to as the ‘Swan of Lichfield’.

One admirer in particular was the Welshman David Samwell. Samwell had sailed with Cook on his third voyage as a naval surgeon and had witnessed Cook’s death in Hawaii. An avid writer and poet himself, Samwell published his account of the incident and later felt compelled to visit Seward at her home, Bishops Palace, in Lichfield, after reading her elegy. And so began a friendship and correspondence that would continue for 18 years.

Portrait of David Samwell, Anna Seward’s long-time friend and surgeon on Cook’s Third Voyage (source – Wikimedia)

On an early visit to Seward, as a token of gratitude for her elegy, Samwell presented her with ‘numerous curiosities from the Southern Hemisphere’, including a ‘feathered necklace called Erei worn by females of the Sandwich Islands and other “Otahitian gifts” that he had collected on the voyage.’

It is not clear exactly what Seward made of the gifts for although she had read Cook’s journals and expressed a keen appreciation for the voyages, she donated Samwell’s gifts to a local museum run by Richard Greene, an apothecary based in Lichfield.

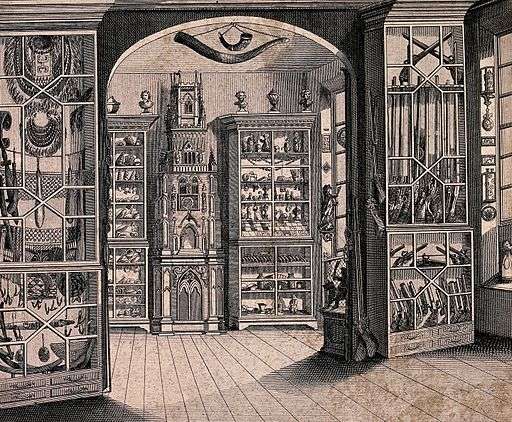

Room inside Richard Green’s Museum at Litchfield, note the Pacific items in the left cabinet. (source – Wikimedia)

Greene, an avid collector and antiquary, displayed the objects in his museum, which at that time, had a widespread reputation and was described in 1776 as “a truly wonderful collection, both of antiquities and natural curiosities, and ingenious works of art. He had all the articles accurately arranged, with their names upon labels, printed at his own little press; and on the staircase leading to it was a board, with the names of contributors marked in gold letters. A printed catalogue of the collection was to be had at a booksellers’.

Like Seward, Greene also counted many intellectuals of the day as friends, including Sir Ashton Lever whom Cook had donated a selection of his own Australian collection to before leaving on his third voyage. Greene displayed Seward’s gifts in his museum and as a result received from the Royal Society their medal in honour of Cook. Seward however, was overlooked.

Indignant and hurt she wrote to Samwell;

‘So little value did the Society which struck the meal in honour of Captain Cooke, set upon my poem on his death that, while they avowedly presented one to every person, who had taken public interest in his fate and his virtues; while they gave Mr Green of this town a medal, merely for having displayed, in his museum, some relics of those illustrious voyages, they took no notice on me.’

The sting of rejection may have faded over time but the oversight was not forgotten. In 1791 Seward again wrote to Samwell:

‘It is curious that your bounty to me enabled Mr Green to display in his museum those Otaheitean curiosities, whose exhibition obtained him a medal. I presented him with a part of your present, and was doubly glad that I had done so, when I found his displaying them rewarded by a distinction which cheered and delighted his honest benevolent heart.’

For a woman such as Seward, intelligent, independent and well connected, it was yet another ‘distinction’ that remained closed to her. Despite being active in an era when patriotism by women was encouraged and her elegy to Cook was praised by the great Samuel Johnson himself, it was still not enough for public academic recognition.

But if Seward was frustrated in life by the reception for her work, it was a relief that she never heard the criticism that was directed at her after her death in 1809. Her friend Sir Walter Scott published her letters after she died, but even he commented;

‘I have not yet read Miss Seward’s letters. God knows I had enough of them when she lived.. She was an uncommon woman; and bating her conceit and pedantry, had some excellent points about her.’

Lord Byron noted that during a dinner party after Seward had died, all present ‘abused Anna Sewards memory’.

It is quite sad to think a woman who was so passionate about so much was forgotten. Her style of poetry went out of vogue and while Sir Walter Scott honoured her wishes and did publish her correspondence, they also faded into obscurity.

But Seward’s ‘Elegy to Cook’ still remains significant as an example of a female voice in a very male arena. Her elegy of Cook, her criticisms of George Washington (which made the President send an envoy to talk to her) highlight that women such as Seward were actively discussing events of the day in the late 18thcentury. Through poetry, letters and salons they remained engaged in debate, critics be damned.

For more curious tales and objects from our collections, head over to our Google Cultural Institute and Flickr pages.