Astrolabe and Zelee in a gale, in the Antarctic Circle in January 1840. ANMM collection 00032388.

It is easy, when reading accounts of early European explorers, to see only the official version they leave behind. The naval reports, detailed charts and an imposing portrait of a confident man in an impressive uniform.

But often, dig just a little deeper and a different man emerges. A man with individual oddities, unsuspected sympathies, personal tragedies and constant worries. Such is the case with the French explorer Durmont d’Urville.

D’Urville is best known to Australians and New Zealanders for his voyages to the Pacific aboard the ship Astrolabe. He published his accounts of these voyages to popular acclaim in France and was referred to as “Frances’ Captain Cook”. But his life, despite his public successes, was not easy and he was often a man at great odds to the task he was assigned.

Portrait of Dumont d’Urville. ANMM collection 00004278.

D’Urville had joined the navy very early and was already serving his second posting by 17. He had a great love of nature and made it clear that achieving naval glory in battle was never his goal:

“I found that nothing was more noble and worthy of a generous spirit than to devote one’s life to the progress of the sciences. Because of this my interests were pushing me towards the navy of discovery rather than the purely military navy”.

It was recorded that at the age of 20 d’Urville met Napoleon, then Emperor, aboard the French ship Amazone. The young sailor was less than impressed with the great man and claimed to see only “the Conqueror in the Emperor, and that was nothing to admire”.

Nine years later, whilst on the Greek island of Milos, d’Urville was shown a recently discovered marble statue. Although damaged, d’Urville realised that it was a significant find and immediately felt that it should be ‘purchased’ for the glory of France. In his account, d’Urville convinced the French ambassador to acquire the statue of a woman, which became known as the ‘Venus de Milo’.

Venus de Milo. Image: Yair Haklai via Wikicommons.

Whether it really was due to d’Urvilles persistence, the statue was ‘purchased’ for France and sent back to Paris and presented to the king.

Once back home, d’Urville publicly associated himself with the discovery of the ‘Venus de Milo’. He was promoted by the King to Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur and started to be noticed by the upper naval ranks. In 1821 d’Urville was assigned to his first expedition to the Pacific.

This would be the first of three voyages d’Urville would take to southern waters, visiting Pacific islands, Australia, New Zealand and ultimately Antarctica. This first voyage on the vessel Coquille saw him as second-in-command and although he resented his lesser role, it did give him the chance to embrace the collecting and recording of specimens that he so loved.

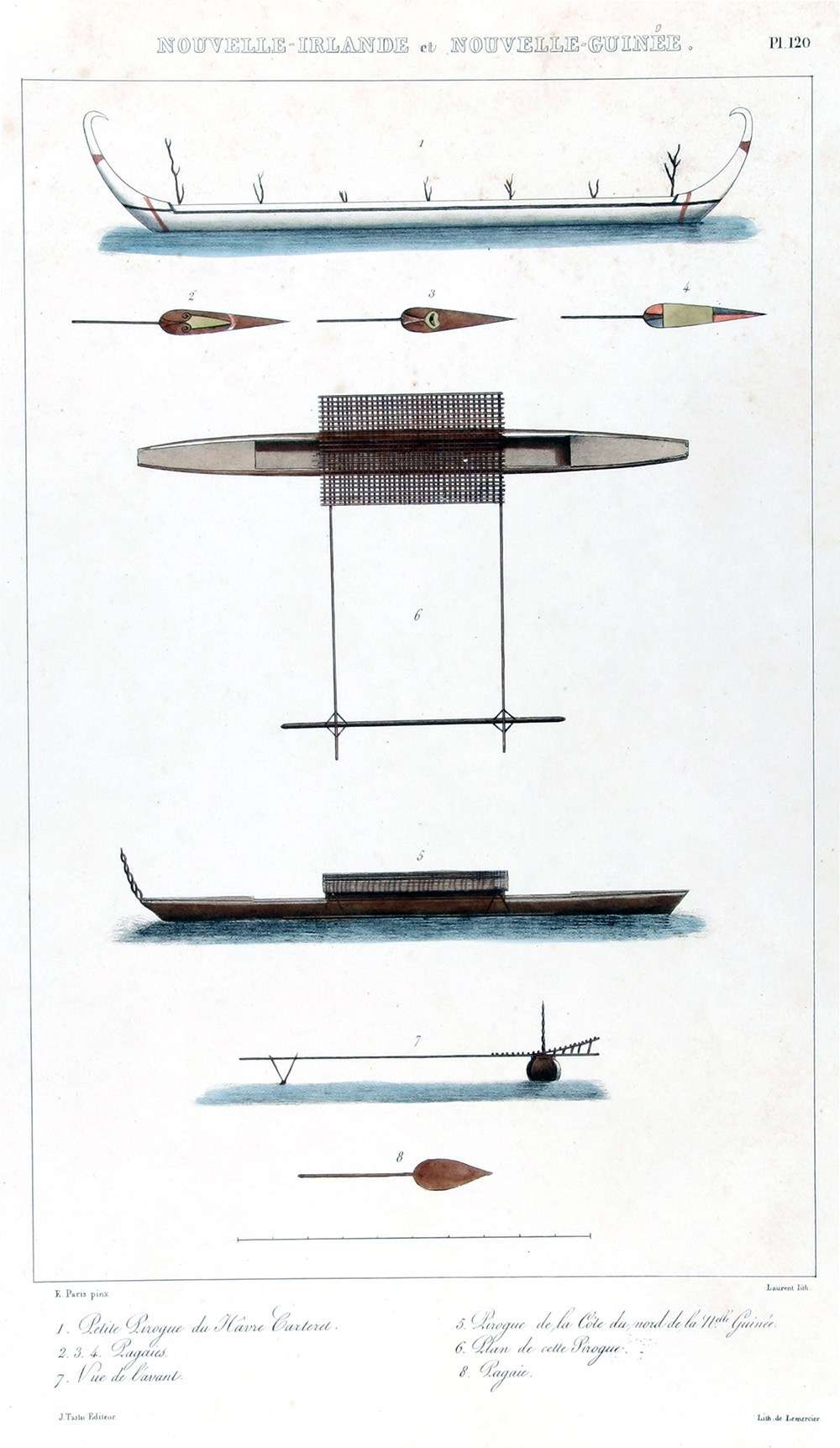

Outrigger canoes from New Ireland and New Guinea. ANMM collection 00046855.

Rene Lesson, the naval pharmacist of the expedition, described d’Urville at this time as shunning any naval uniform and living in a state of “scientific undress”. D’Urville apparently favoured a battered straw hat, old duck drill jacket, ‘threadbare and unravelling” canvas trousers and hobnailed shoes worn without stockings. He was often said to be mistaken for the assistant cook.

This no-frills and careless appearance seems to be have been d’Urvilles preferred state and seems very at odds with the often arrogant and contemptuous private comments he made of some of his fellow officers. He judged them harshly and found fault with much of the leadership of the commander.

On their return to France, d’Urville was given the chance to do the job his way and in 1826 was granted his own expedition south, aboard the Astrolabe. In addition to further survey and collecting work, d’Urville’s brief from the French government was to search for possible safe anchorages for French naval ships and locations to establish a French penal colony such as those established in Australia.

Astrolabe and Zelee, both anchored on a tilt along the Warrior Reef in Torres Strait. ANMM collection 00008309.

The voyage was tough on all and d’Urville lost many of the crew to illness. Whilst there was some negative feedback about his strict discipline aboard, there is no doubt that he felt each death keenly and upon his return to France, he rallied hard for recognition for those who had made the journey with him. Again, this contradiction of the austere public persona and the private anguish of d’Urville is recurrent throughout his life.

Once back in France, d’Urville initially settled into family life at home and found small pleasures in his journals and onshore business. Despite health concerns, d’Urville was niggled by growing thoughts of yet another trip. He talked of Captain Cook’s three voyages and felt that he also had a third voyage in him. When he received directions from the King that a voyage to the South Pole was on the cards, d’Urville was both enthusiastic and yet realistic. He knew that the chance of further glory for himself and France was at stake but also he was aware that:

‘Twice already I had undergone this cruel ordeal, but then I was young, strong and full of hope, optimism and illusions. But in 1837 I was old (47!) subjects to attacks of cruel malady, completely disenchanted and stripped of illusions. So I left behind all that was dearest to me in the word. I voluntarily relinquished the only happiness I could savour, once again to throw myself into the gruelling thankless campaign which was possibly not going to offer me any real compensations. So it was, that when I gave a last kiss to my wife Adele, all these thoughts came to assail me and I could not hold back my tears, and I cursed my sad destiny. But it was too late: I had filled the cup and I had to drink.”

Astrolabe ‘getting in’ water from an ice floe, 6 February 1838. ANMM collection 00029804.

Again, the contradiction in d’Urville is there: Wanting to stay at home in France and yet wanting to experience the unknown. Wanting to be in command and yet wanting to be left to his studies and specimens. He wanted to be respected and applauded by the upper ranks and yet, at sea was happy to be inconspicuous and dress like a ships cook. He wanted to be a good father to his children and support for his wife, but d’Urville wanted to be as recognized as Cook.

The final voyage was no less harrowing than his second. D’Urville and his crew were tested to their limits by the conditions at the pole. He almost lost his ship to the ice and later learnt of the death of yet another of his children and of his wife’s continual decline.

By the time D’Urville returned to France in November, 1840 his own health had deteriorated dramatically and he felt did not have ‘much time left in this world’. Despite the accolades and promotions upon his return for himself and his crew, it is difficult to imagine that d’Urville had thought it worthwhile. Although he had significantly contributed to the collections of various institutions and chartered previously unrecorded waters, the price he paid seems high.

On the 8 May 1842, d’Urville took Adele and their remaining son to Versailles to enjoy the royal gardens, a much needed reprieve from the emotional and physical pressures of their day to day life in Paris. On their return the train in which they were travelling was involved in one of worst train disasters in Europe’s history and all three d’Urvilles were killed. For a man and family who had endured such hardships and were finally together, it seems a particularly devastating way to die.

They are buried together at Montparnase cemetery in Paris and a memorial column placed there recognises d’Urvilles enormous contribution to French exploration and the study of nature in all its forms.

– Myffanwy Bryant, Curatorial Assistant

Curious to see more of our collection? Check out our Flickr and Google Cultural Institute pages to see more stories from the sea.