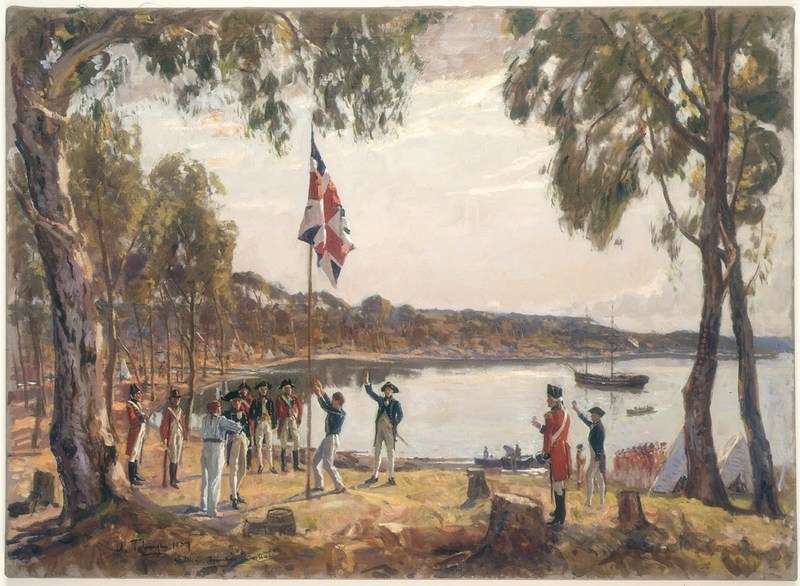

The Founding of Australia by Captn Phillip R N 26th January 1788. Algernon Talmadge, 1937. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

The 26th of January – Australia Day – has long been associated with boats on Sydney Harbour. In 1838, to mark 50 years after the arrival of the First Fleet, a regatta was held, watched from the foreshores by ‘crowds of gaily attired people … bearing the supplies for the day’s refreshments…’ and from the crowded decks of steamers ‘decked out in their gayest colours’.

In the early 1800s, in the colony of New South Wales, 26 January was referred to as First Landing Day or Foundation Day. In a very short time, however, the day had shifted from official toasts to the king at the governor’s table to a people’s celebration.

But the history of Australia Day has taken many more twists and turns along the way. In 1938 it wasn’t thought proper to include convicts in a parade of history through the streets of Sydney. And this same parade was met with a silent group of protesters who called Australia Day a National Day of Mourning.

The Anniversary Day Regatta on Sydney Harbour on 26 January 1848. Oswald Walter Brierly (1817–1894). Pencil and white pastel. ANMM Collection

By the 1830s, the growing numbers of ex-convicts in the colony of New South Wales were clamouring for acceptance by the upper echelons of colonial society. They saw the commemoration of the anniversary of 1788 as a day to celebrate the ‘progress and prosperity’ of the colony since then. From the first Sydney Regatta in 1837, as a newspaper noted at the time, the day was one ‘entirely devoted to pleasure’.

Throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, it was the anniversary of the landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay in 1770 that many people saw as the proper day to commemorate – rather than celebrate – the foundation of the British colony under the first governor of New South Wales, Captain Arthur Phillip. In fact, for many years, 29 April – the day Cook and the crew of Endeavour arrived at Botany Bay – was regarded as Australia’s de-facto ‘national day’. So much emphasis was placed on Cook as the ‘correct’ set of British origins over the arrival of a bunch of convicts, that people often confused Cook and Phillip altogether.

Most Australians in the 19th and early 20th centuries did not greatly care for the fact that the vast bulk of the first British were of convict stock. In fact they really wanted to forget it entirely. But by the 1930s, there was an increasing focus on an Australian history, rather than a history that was about the British in Australia.

At Farm Cove, a huge effort was made in a ‘re-enactment’ of Phillip’s landing and the flag raising that occurred on 26 January 1788. The sea wall was removed to create a beach. The thousands of people watching in the Botanic Gardens could hear Phillip’s every word via a microphone disguised as a tree stump. ‘Captain Phillip and crew raising the flag at reenactment for sesqui-centenary celebrations’. Photographer S J Hood. Citizens of Sydney Organising Committee Archives, City of Sydney Archives SRC19733.

The idea of a national Australia Day based on the arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney was not popular in other states, who had their own ‘arrival’ anniversaries. In fact it wasn’t until 1935 that all Australian states and territories began to use the common name and date of 26 January as Australia Day. And it wasn’t marked as a public holiday in all states until 1994!

The celebrations in Sydney in 1938 were particularly grand, and lasted for weeks. The highlights were the grand parades through the city. This image shows the Sesquicentenary Manufacturers parade. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

No convicts here please, we’re British!

In 1938, for the 150th anniversary, the organisers of a Grand Pageant of Australian history asked people to dress up and provide floats for a historical parade through the city streets. But they didn’t want any convicts. Understandably, some historians and commentators became fairly vocal about this and pushed for the inclusion of all elements of Australian history. They began to ask how could you honestly tell the story of Australian history without any convicts?

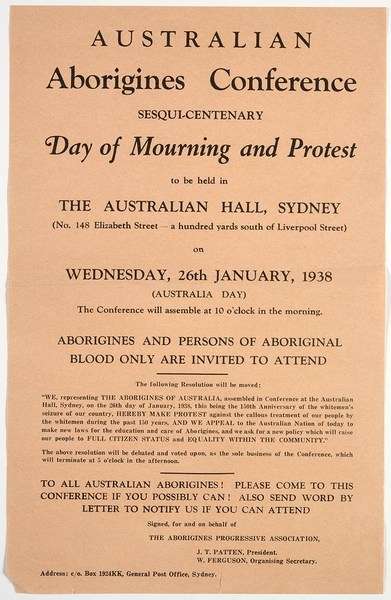

But another group of Australians were so distressed with what Australia Day stood for that they decided to treat it as a day of mourning, rather than celebration. After 150 years of British colonisation and Australian government, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people had very little to celebrate.

Day of Mourning and Protest pamphlet. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

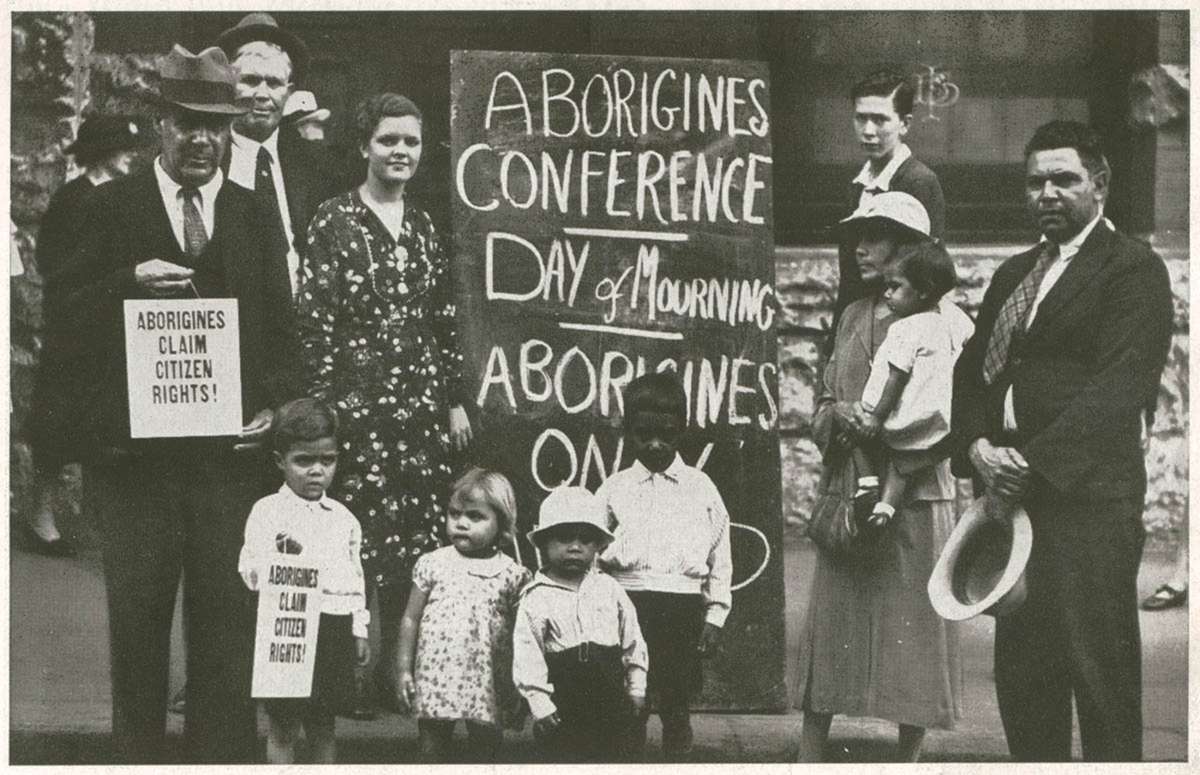

The protest was a significant moment in the growing political recognition of the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. It was also a moment of recognition of their fundamental role in all Australian history. Not just the convicts were missing from history in 1938. So were the original traditional owners of the country, who had been here thousands of years before 1788. In the parade and in a historical re-enactment of the arrival of the First Fleet performed on 26 January, while Aboriginal people were included, they were merely positioned as ‘setting the scene’ for the arrival of the important history – Governor Phillip. Aboriginal people in 1938 wanted to remind people that they had in fact not gone away.

Day of Mourning protesters outside the Australia Hall, 26 January 1938. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Australia Day has been and continues to be contested by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The important 1988 bicentenary protests brought this to the forefront of Australian public attention as the ‘re-enactment’ of the arrival of the First Fleet drew thousands of people to the shores of Sydney Harbour not to celebrate, but to protest.

Some people now argue that the date of Australia Day should be moved to another less divisive date, possibly the day of Federation – or even, if one day in the future Australia should become a Republic, that day could be a better date to celebrate, rather than January 26.

Whatever the case, non-Indigenous Australians have now increasingly begun to recognise that Australia Day has very mixed meanings – not all of them positive. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are now being invited to participate in Australia Day proceedings, to remind all Australians about this.

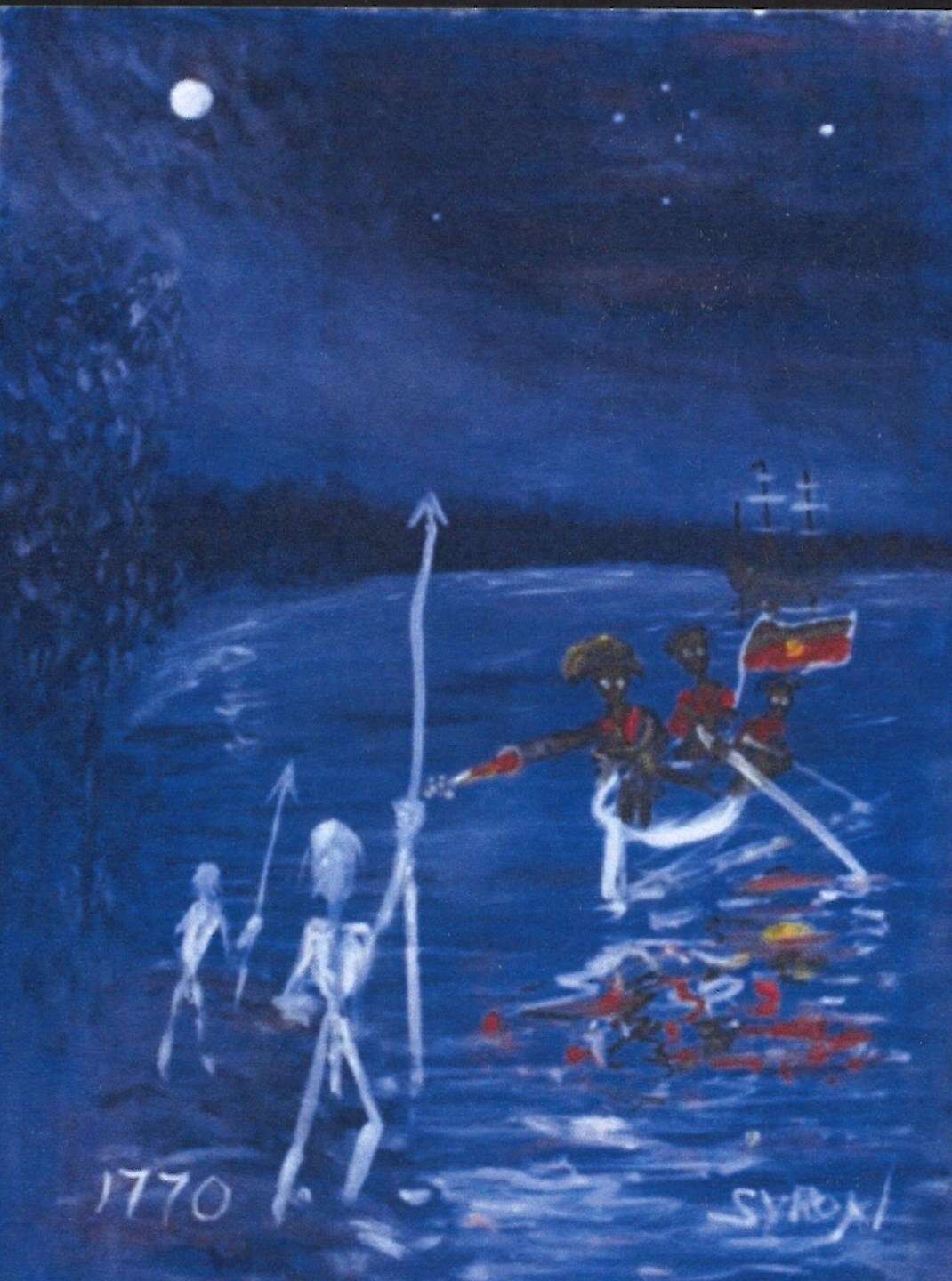

This 2013 painting by Indigenous artist Gordon Syron, titled ‘Black bastards are coming’, reimagines the first arrival of Europeans on the east coast of Australia by juxtaposing Aboriginal warriors with British military. This role reversal has been a common thread in Indigenous art and other cultural production – asking the question ‘how would you feel if it was you who were invaded?’. ANMM Collection

Challenges and possibilities

The museum has a prominent role in interpreting the different and often contested histories and meanings of January 26. We are custodians of the HMB Endeavour replica, which has become an iconic feature of the events on Sydney Harbour. This year Endeavour will be part of the Parade of Sail and will participate in the popular Tall Ships Race.

The museum also holds an important and significant collection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander objects and history related to Saltwater and Freshwater country. Our Indigenous Programs Unit runs several cultural outreach projects currently focused on revitalising bark canoe-making traditions.

If you are at The Rocks on 26 January, look out for two National Maritime Museum pop-up exhibitions at the Overseas Passenger Terminal. In conjunction with local Aboriginal community members and museum staff, we will be acknowledging and honouring our first nations peoples. Displays will showcase our extensive Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs with a traditional canoe-building demonstration, a panel display and videos about traditional watercraft and canoe culture around Australia.

The museum will also highlight migration stories, with an intimate panel and digital exhibition from the museum’s Welcome Wall, which recognises the many people who have come from overseas to make Australia home.

The day will culminate with the launch of the Waves of Migration animated projection across the museum’s rooftop.

The many meanings of January 26 for different Australians continue to provide thought-provoking challenges for the museum as we head towards the 250th anniversary of Cook’s 1770 landing in 2020.

Dr Stephen Gapps, Curator and Donna Carstens, Indigenous Programs Manager

Lawrence Hargrave school students heading to launch a traditional bark canoe (nawi) they made as part of the museum’s Indigenous watercraft outreach program in 2014. Photograph Donna Carstens

The students’ nawi ready for launching on Chipping Norton Lake, part of the Georges River system near Liverpool just south of Sydney. Photograph Donna Carstens