In 1766 Louis-Antoine Bougainville, a 37 year old French army and navy veteran, received his wish from King Louis XV to become the first Frenchman to circumnavigate the globe. In a time of European rivalry, Bougainville’s journey would be an ‘enlightenment expedition’ – not only searching for new lands and the power and glory they would bestow of France, but also of learning. To help him achieve this he took with him the botanist and physician, Philibert Commerson.

Commerson was a man passionate about his field of study and he bought with him a keen sense of observation for all new discoveries – natural, cultural and scientific. He also bought with him something that no one on the expedition could ever have foreseen, a woman.

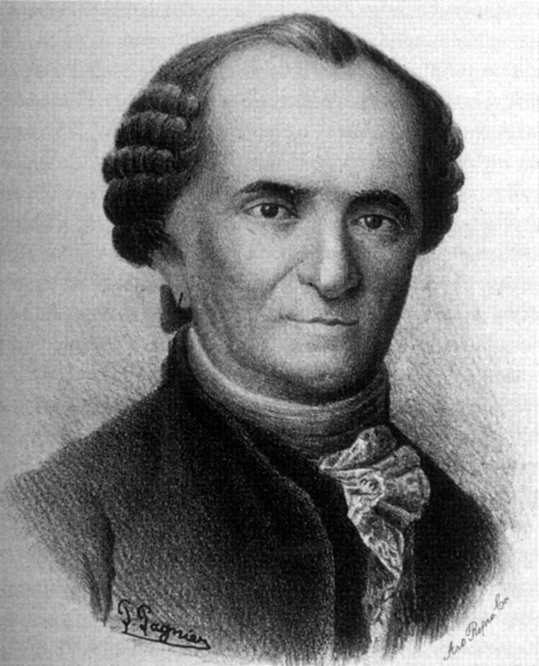

Philibert Commerson, the botanist who relied so much on Jeanne Baret

Women were of course explicitly forbidden on French naval ships and Commercon and his “assistant” had gone to great lengths to conceal her true identity. Her name was Jeanne Baret and she was a skilled and knowledgeable botanist. Whilst never formally trained, Jeanne’s skill as a herbalist had made her a valuable assistant to Commercon prior to his acceptance of Bougainville’s expedition.

Jeanne and Commerson had lived together after the death of Commerson’s first wife. It seems initially Jeanne acted as Commerson’s housekeeper and nurse due his continuous ill health. But clearly intelligent and gifted, Jeanne also became an assistant in Commerson’s botanical studies. Jeanne had given birth to a child that many believe was Commerson’s and yet social conventions and class restrictions seemed to prevent them ever marrying.

Perhaps it was Jeanne’s own sense of adventure and scientific interest , a love for Commerson or a sense of responsibility to care for his health and assist in his studies, that saw the pair convince Bouganville that she, now known as “Jean”, was a Commerson’s male assistant. They were allocated a shared cabin aboard the Etoile where they could work, sleep and store their equipment. This alleviated many of the practical problems of keeping herself disguised from the crew. Nonetheless, suspicion grew on board that all was not quite what it seemed with “Jean”.

Jeanne Baret as “Jean”

Whilst on shore, Jeanne acted as Commeson’s eyes and legs. He was still plagued by leg ulcers and it is unlikely he could have walked the vast distances required to collect specimens. She carried all their equipment and often trekked the terrain alone and armed to ensure no further suspicions would be raised by any perceived lack of strength on her part.

The great reveal came whilst the Boudeuse and the Etoile were at Tahiti. Interestingly it seems it was the local inhabitants who exposed “Jean” rather than the dubious crew. Faced with the situation, Bougainville had no choice but to address it.

‘Bougainville at Tahiti’ by Gustave Alaux, 1930, ANMM Collection

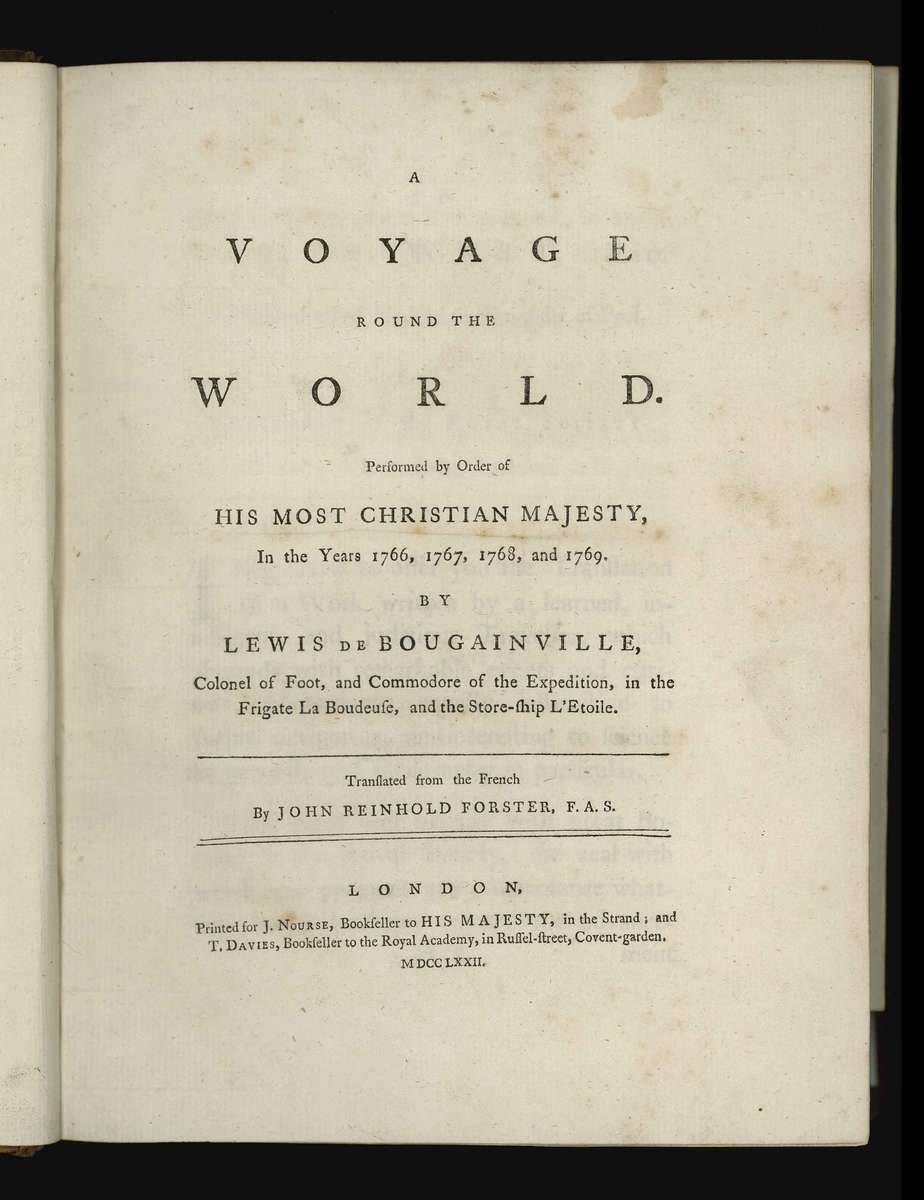

In his book ‘A Voyage Round The World In The Years 1766, 1767, 1768 and 1769’ Bougainville gives a very low key account of the event:

“Some business called me to the Etoile and I had an opportunity of verifying a very singular fact. For some time there was a report in both ships, that the servant of M.de Commerson, named Bare, was a woman. His shape, voice, beardless chin, and scrupulous attention of not changing his linen, or making the natural discharges in the presence of anyone, besides several other signs, had given rise to and kept up their suspicion. But how was it possible to discover the woman in the indefatigable Bare, who was already an expert botanist, had followed his master in all his botanical walks, amidst the snows and frozen mountains of the Straits of Magalhaens, and had even on such troublesome excursions carried provisions, arms, and herbals, with so much courage and strength, that the naturalist had called him his beast of burden?”

Bougainville’s account of his journey which includes the story of Jeanne. ANMM collection

What happened immediately after the discovery is not known for certain. Bougainville states that “after that period it was difficult to prevent the sailors from alarming her modesty” and certainly most accounts acknowledge serious physical repercussions against Jeanne by the crew. She claimed initially that Commerson had not known her or her gender before the expedition and it was her own interest in the journey and a lack of money at home that had caused her to act as she did.

Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, the expedition leader who would become an unlikely ally to Jeanne

Despite the illegality of her ruse, Bougainville seems to have had some sympathy and good will for both Commerson and Jeanne. Once the expedition reached Mauritus, he arranged with Pierre Poivre, the governor there, to ‘acquire the services’ of Commerson to carry out a survey of possible medicinal plants on the island. Poivre, an avid botanist himself and a forerunner in the area of conservation, became a patron of Commerson and provided him with a “huge apartment in his house where he could prepare and conserve his plants, birds, insects.. [Poivre] hosted him at his table, lent him his servants and rewarded his talents in the most generous possible way.”

There is no mention of Jeanne. Can we assume she stayed with Commerson? Safe now in Poivre’s house? It seems she was again pregnant with another son that she adopted out but she was certainly still in Mauritius when Commerson died in 1773.

After this, with Commerson’s death and Poivre replaced as governor, Jeanne was alone. One account tells that she found work as a herbalist or tavern maid and married a French solider. They made their way back to France in 1774 or 1775 and by doing so, Jeanne became the first woman to circumnavigate the globe. She took the considerable trouble to bring back with her the specimens and notes she and Commerson had compiled and the collection became part of the Musee du Roi in Paris.

Jeanne had been left some money by Commerson in his will and although her achievements were not acknowledged publically, she did later receive a small pension from the government in acknowledgment for her work on the expedition. There is one theory that it was Bougainville, who rose to great heights under Napoleon, who ensured this pension was paid to her. While some suggest Bougainville had wanted to distance himself from the fact a woman had been on his expedition, I rather think he admired her for it.

He does acknowledge in his book that in going around the world:

“she will be the first woman that has ever made it, and I must do her the justice to affirm that she has always behaved on board with the most scrupulous modesty.”

Jeanne died in 1807 at the age of 67 but it was not until 2012 that a fitting tribute to her was created. Eric Tepe named a new plant species from southern Ecuador and northern Peru after her. In his dedication of ‘Solanum baretiae’ Tepe says:

“We believe that this new species of Solanum, with its highly variable leaves, is a fitting tribute to Baret.” They describe the plant’s namesake as “an unwitting explorer who risked life and limb for love of botany and, in doing so, became the first woman to circumnavigate the world.”

Solanum baretiae

The plant named for Jeanne in 2012.

Myffanwy Bryant