A hut still standing near the site of Camp Victory in Casino, northern New South Wales. Photograph courtesy Anthony Liem.

On October 24 this year over a hundred people gathered in Casino in Northern New South Wales to commemorate the 70th anniversary of an event not widely known in Australian history. In late 1945 residents of the sleepy rural township of Casino were dramatically drawn into the events surrounding the struggle for Indonesia’s independence from the Dutch.

After the Japanese invasion of Indonesia in 1942 the Dutch, who had been the colonial power in Indonesia for over 300 years, fled to Australia. The Dutch Government in exile brought with them Indonesian soldiers, sailors, government officials and others.

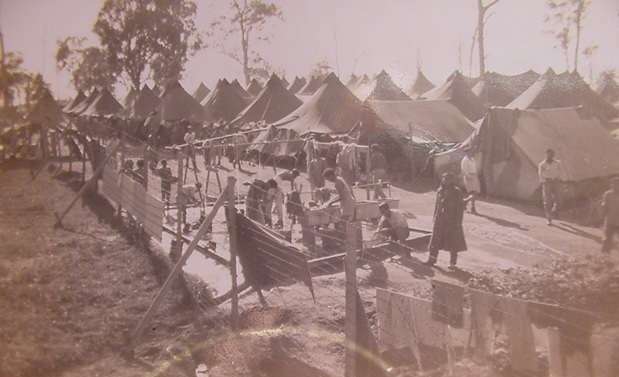

Camp Victory, Casino c. 1946. Photograph courtesy Casino Historical Society and Anthony Liem

From December 1943 a few hundred Indonesian soldiers arrived in Casino as part of the Dutch Armed forces Technical Battalion. They trained and worked in preparation for the Dutch return to Indonesia when the war was over. Although Australia was still under the race-based immigration restrictions of the White Australia Policy — and these soldiers would not have otherwise been allowed in the country — it was wartime, and they were part of the Dutch armed forces.

Casino in 1946. Photograph courtesy Casino Historical Society and Anthony Liem

The soldiers also had soldiers’ pay, and after work hours finished they would visit the small township of Casino. Apparently they were good business in the local shops — many long-term Casino residents recalled them buying bicycles and having a fondness for perfume. They also remember the soldiers showing them how to make and fly kites.

At the end of the war in August 1945, the army camp in Casino had become known by the Dutch as the Victory Camp. Between 1943 and 1945 other elements of the 10,000 Indonesians who had arrived in Australia with the fleeing Dutch government began to arrive at the camp. Some of these were anti-colonial Indonesian nationalists who had been imprisoned by the Dutch, who thought they would be a danger if left behind in Japanese controlled Indonesia.

But tension was to grow in the normally sleepy township best known at the time for its dairy industry. The first word of the Indonesian declaration of independence reached Camp Victory in September 1945, and along with it came orders from the new Republic to ‘defy the Dutch’. By 12 September many of the soldiers declared they were no longer under Dutch jurisdiction. They were hastily imprisoned by the Dutch guards and almost overnight Camp Victory was surrounded by floodlights, watchtowers and a barbed wire fence.

A watchtower at Camp Victory. Photograph courtesy Casino Historical Society and Anthony Liem

Indonesian sympathisers in Australia — mainly from the left-wing maritime trade unions who had black banned Dutch ships returning to Indonesia — began to publicise their plight, some describing Camp Victory as a ‘little Belsen’, akin to a Nazi prison camp. During the next few months many of the Indonesian soldiers around the country refused to obey the Dutch and were promptly shipped to Camp Victory to be court martialled. By October there were around 400 prisoners. They sent a letter to the Prime Minister on 29 November explaining they were no longer Dutch subjects and demanded release.

But they were court martialled by the Dutch and received prison sentences. While their plight increasingly came to the attention of the public and activists such as Molly Warner were writing to the Prime Minister, they continued to be imprisoned throughout 1946.

After two deaths in the camp — one possibly a suicide — on 12 September guards opened fire at a protest by the Indonesians. One defiant ex-soldier named Soerdo was shot dead and two others wounded. Sympathisers, Casino residents, the press and now the Australian government were outraged.

By October the prison sentences of the first 200 ex-soldiers had ended and they were released, discharged from the Dutch armed forces and sent to Brisbane for repatriation back to Republican-held Indonesia. While the Dutch further incensed the Australian government by secretly transferring 13 of the ‘ringleaders’ out of the country, by December the remaining 300 prisoners were released.

Pak Konjen and Ibu Konjen from the Indonesian Consulate in Sydney were guests of honour at the seminar. Historian Jan Lingard was the main speaker and members of Casino Historical Society and Grahame Irvine from Southern Cross University in Lismore provided background information on the Army Camp and the Indonesian soldiers. Photograph courtesy Anthony Liem

The seminar re-visiting these events from 70 years ago on 24 October 2015 was jointly organised by the Australia Indonesia Association (AIA), the Casino Historical Society and the Richmond River Council. The forum created much interest with about 100 people in attendance including some long term Casino residents who remembered the infamous Camp Victory and the Indonesian prisoners.

A visit to the site of the camp provided an opportunity for some of them to talk about their recollections of the camp from 1943 to 1946. Many remembered the Indonesian soldiers who refused to serve the Dutch very well and some had in fact became good friends during this period.

As historian of the period Jan Lingard wrote, the Casino events saw the Indonesian Revolution come to an Australian country town. In a strange and largely forgotten twist, this sleepy rural township in northern New South Wales was where some of the first Indonesian blood of what was to be a long and protracted war to maintain independence, was spilt — far from Indonesia, on Australian soil.

A remnant of Camp Victory, possibly an ammunition store. Photograph courtesy Anthony Liem.

Further reading:

Jan Lingard Refugees and Rebels: Indonesian exiles in wartime Australia Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2008