Notopogon fernandezianus (Orange Bellowsfish). Credit: Sandra J. Raredon. © Smithsonian Institution

Have you explored the striking images on display in X-Ray Vision: Fish Inside Out? The Smithsonian Institution’s Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES) produced the exhibit on at the Australian National Maritime Museum until 28 February 2016; it features 40 black-and-white digital prints of x-rays or radiographs arranged in evolutionary sequence, taking visitors on a tour through the long stream of fish evolution.

Curators of the exhibition, Lynne Parenti and Sandra Raredon, work at the National Collection of Fishes at the National Museum of Natural History. Sandra prepares thousands of x-rays to help ichthyologists understand and document the diversity of fishes. Here, Lynne, a research curator, describes what’s involved in capturing these mesmerising x-ray images.

Radiographs or x-rays allow the study of the skeleton of a fish without dissecting or in any other way altering the specimen. Radiographs may be prepared of any specimen, often unique or rare specimens, or, alternatively, large samples in which a researcher wishes to compare features among a group of individuals.

The radiographic images in this exhibit largely follow scientific, not artistic, conventions: there is one specimen per frame, and that individual fish is facing left. When grouped together, they are done so to save time of radiograph preparation or to facilitate comparison.

Selene vomer (Lookdown). Credit: Sandra J. Raredon. © Smithsonian Institution

Characteristics of the skeleton can be seen readily: number of vertebrae, number of fin spines, configuration of the bones that support the caudal or tail skeleton, the relative size and shape of the jaw bones, or the presence or absence of teeth in the jaws. The results of such comparisons are published in the scientific literature on fish systematics and taxonomy, and the images become part of the archives of the Smithsonian’s National Collection of Fishes.

Sandra Raredon selects specimens to be x-rayed. Photo: Chip Clark. © Smithsonian Institution

Radiographs are relatively quick and easy to prepare on modern digital x-ray systems. Sandra Raredon has mastered the digital x-ray technique at the Division of Fishes at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. Here, Sandra demonstrates the process used to prepare the x-ray of the three specimens of the Lookdown, Selene vomer, one of the most popular images in this exhibit.

Sandra Raredon arranges the three specimens. Photo: Chip Clark. © Smithsonian Institution

She first selects the best specimens to x-ray: those that are relatively flat, not bent, and with complete, not broken, fins and fin rays. Larger specimens may show greater detail than smaller specimens, but ultimately the specimens chosen are those of scientific interest. The arrangement of the three specimens is deliberately artistic, but also makes it easy to compare one specimen to the other.

Sandra Raredon transferring specimens to the x-ray machine platform. Photo: Chip Clark. © Smithsonian Institution

The selected specimens are transferred to the x-ray machine platform. A beam of x-rays is generated and focused on the fish specimens, which absorb some of the rays. Bone is a dense tissue that absorbs most of the x-rays, whereas soft tissue such as the heart or gut absorbs fewer. Sandra controls the x-ray machine using a computer in a separate room. The x-ray machine room has a lead-lined door and walls to protect Sandra and others from exposure to the radiation. X-rays cannot pass through lead. While the x-ray machine is on, the door is closed.

Sandra controls the x-ray machine using a computer in a separate room. Photo: Chip Clark. © Smithsonian Institution

The x-rays that pass through the three Lookdown specimens are captured on a digital detector, which produces an image that makes the specimen appear transparent: bone is white, and soft tissue is grayish-black. The x-rays in this exhibit were taken at exposures of 30 to 70 kilovolts for 5 to 10 seconds, depending on the size and density of the fish.

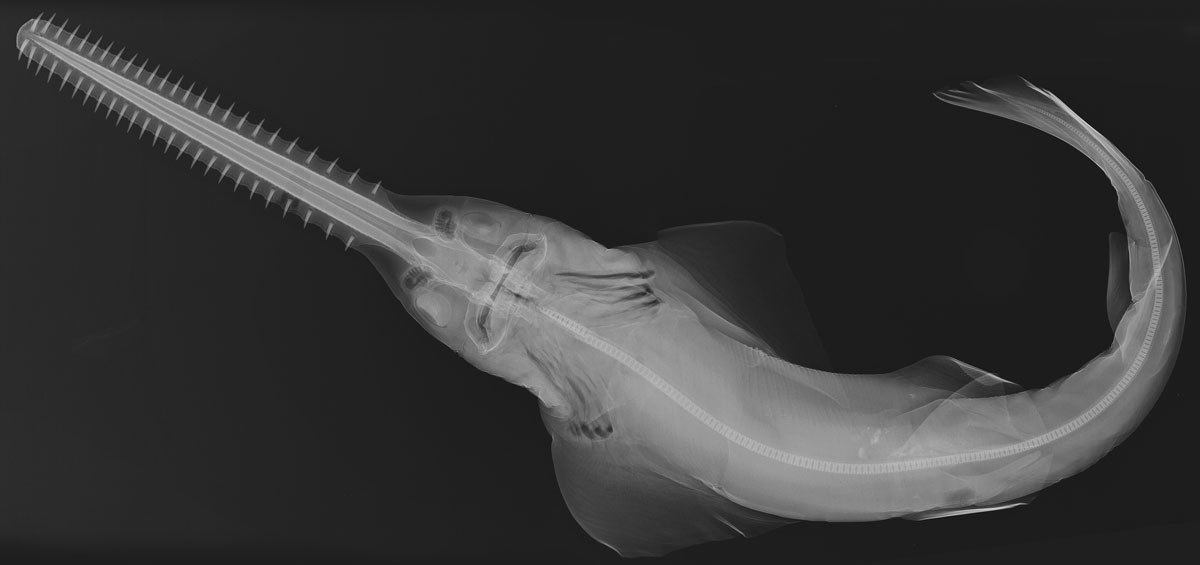

Pristis pectinata (Smalltooth sawfish). Credit: Sandra J. Raredon. © Smithsonian Institution

The platform on which the specimens are placed is about 36 centimetres by 40 centimetres in size. Specimens that are larger than that may be x-rayed, but in more than one image. The Smalltooth sawfish, Pristis pectinata, specimen was too big for the platform and was x-rayed in two parts. You can see where the two images were ‘knit’ together at the base of the head where the vertebrae are not aligned perfectly.

You can see the x-rays up close at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney: X-Ray Vision: Fish Inside Out is on display until 28 February 2016. These and other images also available to view on Flickr and in the book Ichthyo: the Architecture of Fish. X-rays from the Smithsonian Institution.

Lynne R. Parenti

Curator, Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History

Portions of this text appeared in Parenti, L.R. 2008. Ichthyology at the Smithsonian: The collection and research in the Division of Fishes, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, pp. 160-169, In: Ichthyo: the architecture of fish. X-rays from the Smithsonian Institution. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, CA.