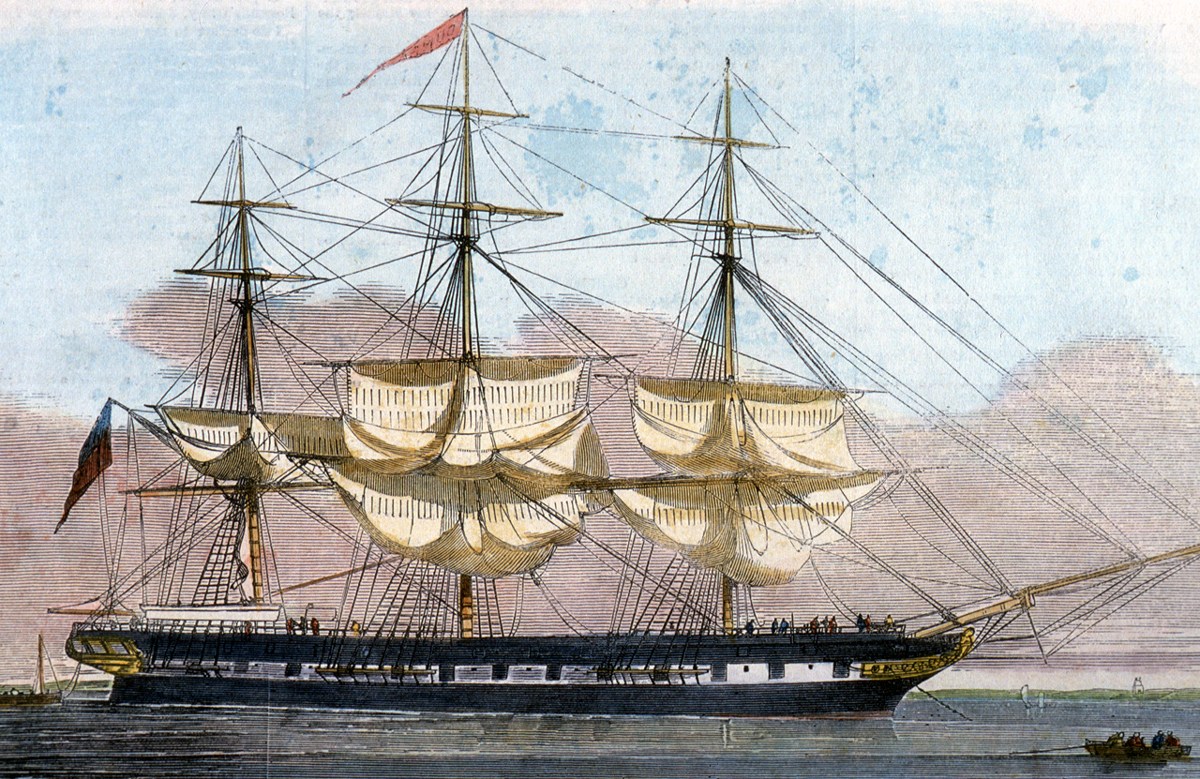

Illustrated London News (24 December 1853). ANMM Collection 00000957.'>

Illustrated London News (24 December 1853). ANMM Collection 00000957.'>‘The Dunbar New East Indiaman’, Illustrated London News (24 December 1853). ANMM Collection 00000957.

Shipwreck on a stormy winter’s night

The devastating wreck of the Dunbar on Sydney’s South Head on the evening of 20 August 1857, 158 years ago, was a disaster so appalling that it left a lasting emotional scar on the emerging colony of New South Wales.

In the pitch-darkness of that stormy winter’s night, Dunbar – only moments from safety at the end of an 81-day voyage from Plymouth carrying immigrants and well-to-do colonists returning to Sydney – missed the entrance to Port Jackson and crashed into the sheer sandstone cliffs just south of the heads. The heavy seas quickly pounded the ship to pieces, and all but one of at least 122 souls on board perished.

Devastation at the Dunbar disaster

As dawn broke, Sydney awoke to dreadful scenes of debris and battered corpses carried into the harbour on the tide. The impact of the disaster was profound with many of the victims coming from well-known prominent families – such as the Waller’s who lost two adults and six children and the Meyers who lost two adults and at least four children in the wrecking of the Dunbar.

A Narrative of the Wreck of the Dunbar, 1857. ANMM Collection, 00009344.

Some 20,000 people lined George Street for the funeral procession, and there was a massive outpouring of grief in the colony – still evident today with the yearly Dunbar service at St Stephen’s Church in Newtown.

The tragedy quickly spawned a small industry commemorating the disaster. Accounts were published and pamphlets, poems and paintings proliferated. Soon, despite demands from authorities not to plunder the wreckage washing ashore, memorabilia made from the ship’s timbers began to appear and furniture, tableware and souvenir boxes have survived, passed down as treasured mementoes.

The Captain’s Chair

One such relic is a solid timber chair known for years as ‘The Captain’s Chair’. The mid-19th-century diary of Florence Fraser, the great-great-grandmother of the last owner, says it was recovered from Bondi beach. Its excellent condition however – with no signs of damage or repair – suggest it was neither cabin furniture nor cargo, since it would be most unlikely to have washed ashore unscathed. Unusually, the seat and back are carved from a single timber, probably an angular piece of ship’s framing called a ‘knee’. Once salvaged it was probably created by a local cabinet maker dabbling in Dunbar souvenirs.

Dunbar, 1857. ANMM Collection, 00046922.'>

Dunbar, 1857. ANMM Collection, 00046922.'>Captain’s Chair, constructed from timber salvaged from the wreck of the Dunbar, 1857. ANMM Collection, 00046922.

Unlike the ship’s timbers that washed up, most of the ship’s cargo, fittings and passenger belongings sank onto the rocky seabed of the wreck site. Mid-19th century salvage technology enabled some larger items such as the anchors to be raised, but countless smaller items remained wedged in crevices for another century, awaiting discovery. Then, from the late 1950s, devotees of the new sports of spearfishing and scuba diving found easy pickings in the shallow waters, just a short dinghy-ride from the harbour in calm weather.

1960s: Recovering more artefacts

The trove of artefacts retrieved from the Dunbar site by diver John Gillies in the 1960s was gathered at a time when there were few government controls on such activities, and little interest in protecting our underwater cultural heritage. Over 10 years, sometimes using explosives to break up concretions, Gillies recovered a huge range of items – coins, trade tokens, cutlery and personal effects including watches, jewellery and gold denture plates (some complete with teeth) along with buttons, buckles and furniture, piano, gaslight and plumbing fittings.

From the 1960s, a growing number of divers began to take a more conservation-minded approach. The Maritime Archaeological Association of NSW was formed in 1978 – largely by former recreational salvage divers – to raise public and government awareness of the historical and archaeological treasures as they lay buried beneath the sea. One of the first wrecks investigated was that of the Dunbar.

A small selection of the ANMM Dunbar collection, purchased with the assistance of the Andrew Thyne Reid Charitable Trust

Legal protection for shipwrecks

Thanks to their action and those of other like-minded individuals the Dunbar was protected under historic shipwreck legislation. Following on from that protection in 1993, the Australian Government offered an amnesty in order to record material from protected shipwrecks, and John Gillies declared his collection of over 5,000 Dunbar objects.

The museum acquired this significant collection to prevent it falling into private hands or being broken up. Thousands of artefacts have since undergone conservation, registration and curatorial research. Other relics – including anchors, ballast blocks, coins and crockery fragments – remain on the seabed and the site, which has been surveyed and monitored with the aid of this museum’s maritime archaeology program, is itself a memorial to those who perished so miserably in the Dunbar tragedy on that night in August 1857.

– Kieran Hosty, Manager – Maritime Archaeology Program

Artefacts from the Dunbar are on display in the museum’s Passengers gallery.