100 years after the Anzac landings at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, the museum has acquired a rare diary written on board a transport ship lying off Anzac Cove.

Engineer George Armstrong. George met his wife Alice Sarah Armstrong (nee Poole) just before World War I. Alice was born in Waverley, Sydney, and met George on one of his regular visits to Australia working as an engineer on various Scottish Clan Line cargo ships. ANMM Collection Gift from David Matheson

Described by a fellow sailor as a ‘burly Tynesider’, George Armstrong was born in Eastfield Lanark, Scotland in 1882 and began his maritime career as 5th Engineer on the cargo vessel Clan MacPherson in 1903. By 1906 he had advanced to 3rd Engineer, working on several of the well-known Glasgow-based Clan Line vessels.

A45 was an ex-German ship, the Hessen, one of 25 German ships that were captured or impounded in Australia at the start of the war. It arrived in Alexandria, Egypt, on 10 March 1915 and the crew learned that they were to await the outcome of the planned Allied naval assault of the Dardenelles Strait, which would hopefully knock Turkey out of the war by bombarding the capital, Constantinople (Istanbul).

But on 18 March, in what is still celebrated today as a great Turkish victory against the mighty British and French navies, the Battle of the Dardanelles (known as the Battle of Çannakale in Turkey), the Allied fleet could not force the heavily mined and fortified straits and suffered heavy losses. It was then decided that the infantry would land on the Gallipoli peninsula.

After visiting the pyramids in Cairo, in early April the crew of A45 were directed to convey the 26th Indian Mountain Battery with its personnel, mules, guns and supplies to an ‘unknown destination’.

A45 entered Mudros Harbour at the Greek island of Lemnos and joined the massive assemblage of Allied ships at anchor. According to another crew member A. Ward Guthrie, A45 hoisted ‘an eighteen foot blue Australian ensign’, but was soon told to haul it down and hoist the red British ensign instead: ‘It was the first time the southern cross had been displayed in these waters, our vessel being the only Australian in the armada’.

On 24 April a course was set for the Gallipoli Peninsula. Armstrong wrote ominously in his diary:

There will be a big loss of valuable lives before they affect a landing as the Turks are very strongly entrenched. It is awful to think of. … I don’t think that people realise that this is going to be a desperate business here.

Speculation about the impending attack was rife. Armstrong described how the crew formed an opinion that they had been tasked with running the ship up on the beach and ‘using her for landing’. He then promptly went to the ship’s bosun and asked him to make a canvas bag to put his gear in, ‘in case we have to clear out in a hurry’.

Shortly before 6 am, those who were able to sleep on A45 were awoken by the thunder of battleships’ guns as they began their task of supporting the landing. A45 lay at anchor and in the range of Turkish guns, ready to disembark its Indian artillery unit.

At 9 am Armstrong looked out across an incredible scene: ‘Shells dropping all round us … Troops landing all the time … Queer sensation the shells passing overhead knowing one is enough to send us to the bottom.’

Armstrong’s sketch of the landing on 25 April is a wonderful personal ‘birds-eye view’ of the scene from near the position of A45 – which Armstrong has labelled as Hessian (he meant Hessen – the previous German name of the vessel). Armstrong notes various prominent locations of the Gallipoli Campaign, including Lone Pine and Suvla Bay, suggesting the sketch was compiled or annotated sometime after 25 April. ANMM Collection Gift from David Matheson

The queue to get troops ashore grew throughout the morning and A45 had to wait under intermittent Turkish artillery fire. Finally at 10 am, lighters came alongside and half the artillery were unloaded. Mules were lifted over the side with ‘belly straps under the squealing and protesting’ animals. The Indian artillerymen, dressed as ‘though for parade’ were put on boats with, according to Guthrie, all their ‘guns, ammunition, accoutrements, camp gear, signalling apparatus, and our fervent good wishes’. Armstrong noted how the mules ‘kick out some’ and he didn’t care to get too close to them.

An Indian mountain artillery battery in action. Australian War Memorial, A03150

Armstrong watched the first day of the Gallipoli landings in awe. He described it as a ‘grand day’ and ‘a marvellous sight’. The vision of aeroplanes, observation balloons, battleships, and masses of troopships and landing craft streaming ashore urged him to record the scene in a remarkable sketch. One can imagine the crew lined on deck, craning to see what was happening. As he noted on 27 April, ‘we cant keep away from the ship’s side these days’.

The night of 25 April, the shelling ‘went on right through the night’ and by the 26 April had ‘scarcely stopped at all’. By the 27th, the heavy guns were still ‘going all day’ and the machine guns had ‘hardly stopped’. Armstrong could see the flashes from Turkish machine guns right along the hilltops at times. One Allied battleship was anchored ‘about a ship’s length’ from A45 and ‘firing 12 inch guns all the time’.

Another diarist on board transport A45, engineer Jesse Garton, noted how the shell fire from Queen Elizabeth ‘made the whole ship tremble … like a tree in a gale’.

By 28 April, the spectacle had worn off considerably and Armstrong wrote, ‘It looks as if it was going to be a long job’. After receiving some wounded members of the ships company back from landing troops he wrote, ‘It seems queer to be writing this so close to where the actual fighting is going on’.

Armstrong recorded accounts of the action that he heard from other soldiers and sailors. Often this was more wild rumour than truth. On 29 April Armstrong wrote that ‘news came of the [Australian submarine] AE2 getting through the Dardanelles into the Sea of Marmora’ [sic – Marmara]. He also heard it had returned safely – which it hadn’t.

AE2, the only Australian navy unit at Gallipoli at this point, had indeed forced the Dardanelles Strait, but had been scuttled several days later after a fight with the Turkish torpedo boat Sultanhisar. Armstrong did later note that it was ‘funny how these reports get about’.

By 30 April Armstrong began to describe the campaign as ‘pretty severe’, recording casualties of ‘3500 soldiers’. His excitement at the spectacle of Anzac Cove began to turn into despair. By May 4 he wrote:

[Our] 2nd mate and 4th engineer … are pretty sick of it. They were at one of the landing places and it seems the troops got cut up pretty bad. Some of the boats were filled up with dead bodies …

A45 moved out of artillery range and remained anchored near the battleships at Gallipoli for another three weeks, operating as a water supply and, as Armstrong noted, ‘a hospital ship for mules’. The ship returned to Alexandria on 20 May and then went on to London. It later returned to Australia and then served in the North Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Indian and Pacific oceans during World War I.

George Armstrong returned to Australia and married Alice, living in Waverley, Sydney with two children, Andrew and Alice Elizabeth. He went into partnership in an engineering business, Nicol Bros, which was well known on the waterfront at the Sydney suburb of Balmain for many years. George died during World War II, not long after the death of his son Andrew. While George had survived WWI on his transport A45, Andrew was an engineer in the Merchant Navy on the ill-fated SS Ceramic which was torpedoed by a German submarine and went down with 655 dead and only one survivor, picked up by the submarine.

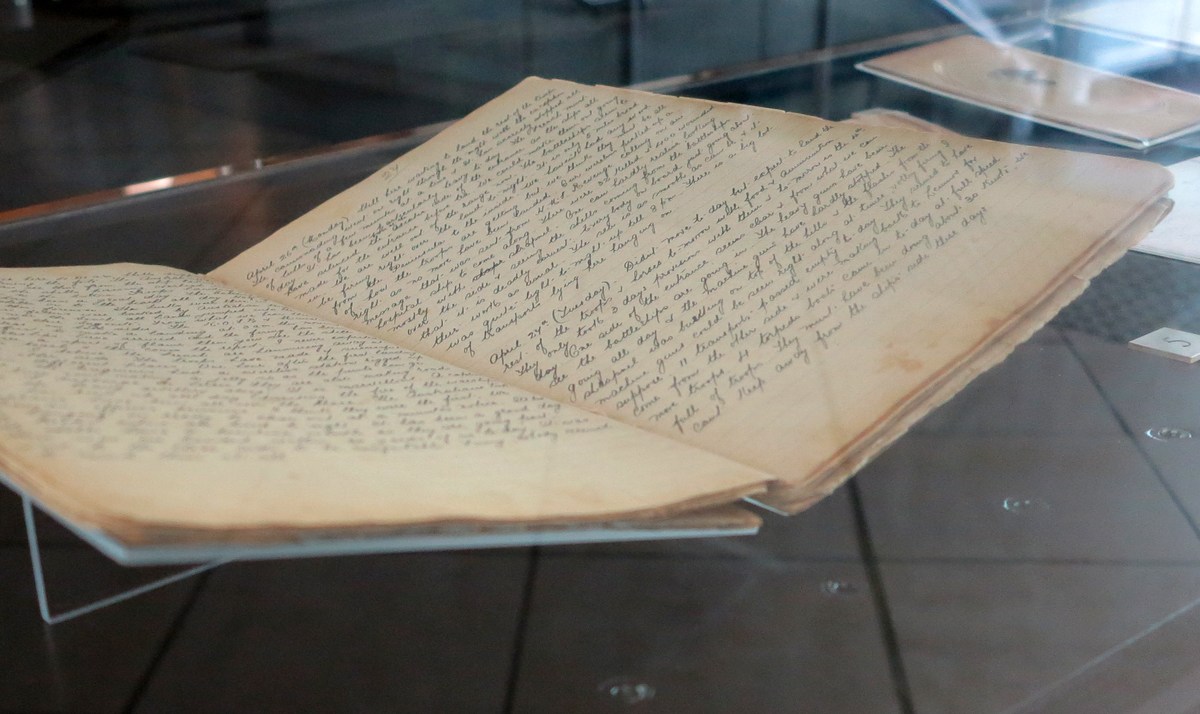

George Armstrong’s diary open on 25 April 1915. ANMM Collection Gift from David Matheson

Armstrong’s diary is written in wonderfully clear handwriting in ink in a foolscap exercise book with a card cover and blue-lined pages. It begins on 2 February 1915 with his ship leaving Melbourne bound for ‘London via Colombo or Egypt’ and ends on 3 July 1915, just before arriving in England.

George Armstrong’s diary is an important addition to the National Maritime Collection, recording an unusual perspective of the Anzac landings. The diary has not previously been published, remaining in the hands of the Armstrong family until recently, when they generously donated it to the museum. It will feature in a display in the museum foyer during the Anzac Day centenary period and will be transcribed and made available online.

George Armstrong’s diary on display at the Australian National Maritime Museum

More information about the Royal Australian Navy in WWI can be found in the museum’s exhibition War at Sea – The Navy in WWI which runs until 3 May, and will then travel to various regional and interstate destinations until 2018.

Dr Stephen Gapps, Curator

Further reading:

Guthrie, A Ward. ‘The captured German ships in Egypt and the Dardanelles’ [online]. Sabretache, Vol 40, No 4, Dec 1999: 3-15.

Jesse Garton diary 5/4/1915–21/5/1915, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK JOD/255/1

Ceramic Casualties; http://www.ssceramic.co.uk/casualties/search.php