“These men took pride in the fact they were the only Australian naval unit serving in the European theatre of war … They were therefore bent on proving to the Royal Navy and the Army that they could overcome any difficulties”.

CMDR L. S. Bracegirdle, RN, commanding the Royal Australian Navy Bridging Train at Gallipoli, 16 November 1915

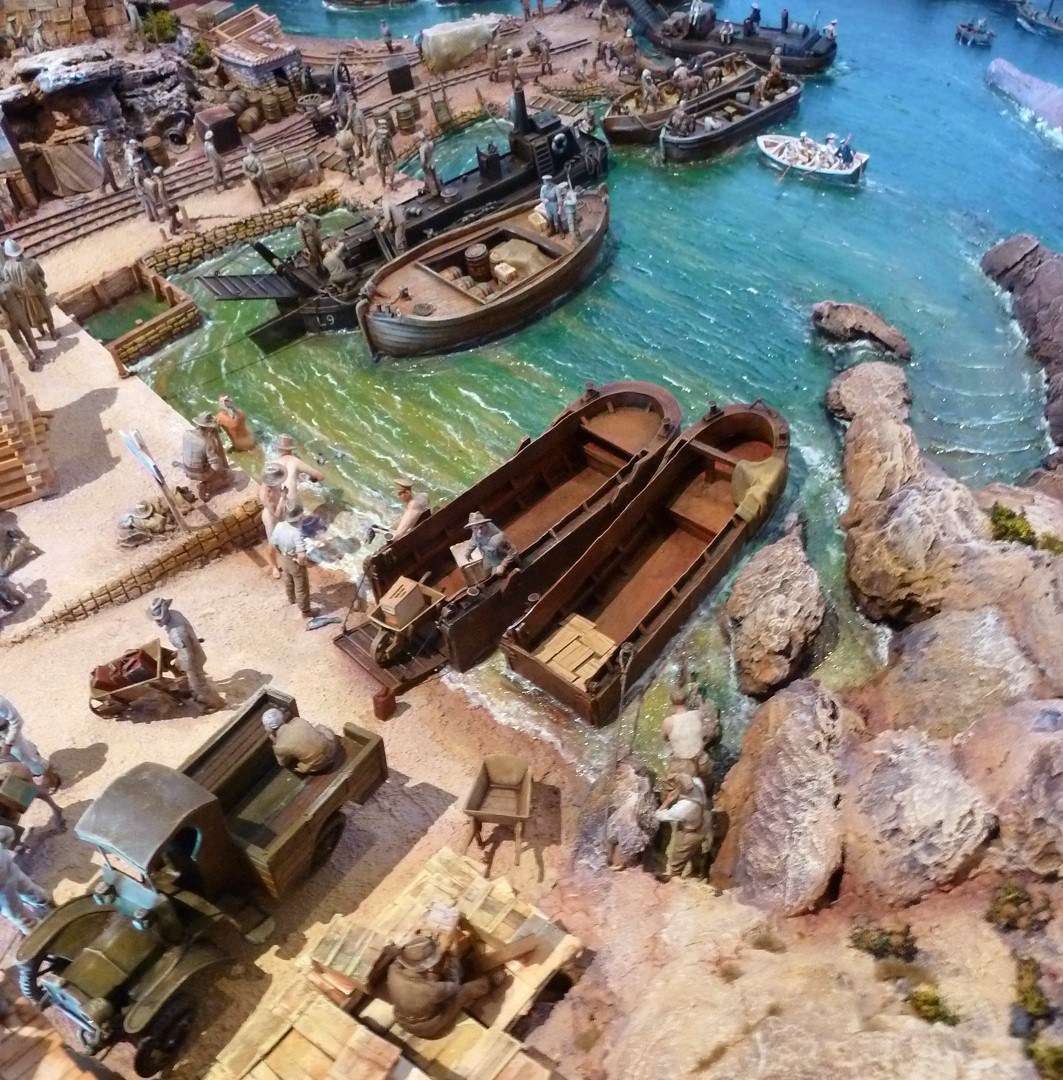

One of the most popular parts of the War at Sea – The Navy in WWI exhibition at the museum is a wonderfully old-school diorama. It has no bells or whistles. You can’t swipe, touch or play with it — apart from a series of buttons that light up various sections. But everyone — even the ‘walk through’ visitor — stops and checks it out.

The same goes for the dazzle ship models on display at the model-makers bench. Perhaps it is something to do with a sense of scale — things replicated in miniature have always held a fascination for people. We can see a scene from a birds-eye view of tangible 3D recreations of people just like us. So too, with objects that usually dwarf us, we become the giants. The relationship between a sense of self and one of scale has always been an important one.

Whatever the case, the diorama in the exhibition has been one of the highlights of the War at Sea displays.

I leave it for the diorama maker — museum volunteer Geoff Barnes — to take up the story of the men from Kangaroo Beach and explore in detail all the frenetic activity jam-packed into the various diorama scenes.

An unfortunate ommission

Scene from an Australian War Memorial diorama showing Anzac troops being ‘cut down’ at The Nek

When the Australian War Memorial was conceived in the aftermath of World War I in the 1920s, a key part of the collection was to be a series of dioramas. These would be meticulously researched and painstakingly sculpted three-dimensional representations of important moments in Australia’s military history, set in painted landscapes, capturing moments in time in way that photographs, films, paintings or cases full of artefacts could never achieve. These dioramas still prove to be a very popular and unique collection.

But there was an unfortunate omission. They dealt solely with the Army’s war, and the Royal Australian Navy was not included. Now, nearly a century on, the diorama in the exhibition War at Sea – The Navy in WWI brings to life the story of an unlikely set of heroes — the Royal Australian Navy Bridging Train at Suvla Bay.

At the urging of Winston Churchill, the British and Allied Forces dreamt up a bold and imaginative to frighten Turkey out of the war with a swift and decisive blow. A combined British and French battle fleet would sail into Constantinople harbour and capture the capital of the Ottoman Empire. Great idea, but they didn’t even make it through the narrow Dardanelles straits. In a great victory for the Turks, on 18 March 1915, battleship after battleship was sunk by underwater mines and coastal artillery. It soon became obvious that the Turkish fortifications had to be captured by land forces before the navies could be guaranteed safe passage.

So in April 1915 a major British force, reinforced with the Empire’s colonial forces from Australia, New Zealand and India, as well as French colonial forces, went ashore on the western, Aegean Sea side of the peninsula. The intention was to storm up the heights, pour down the eastern side and destroy the Dardanelles batteries. But the Turks had plenty of warning, and proved to be much tougher than was anticipated. The terrain was much more difficult than the maps suggested, and the Allies met fierce and well-coordinated resistance from the Ottoman Army.

What had been planned as a bold strike to knock Germany’s ally Turkey out of the war quickly became a stalemate just as wasteful and draining as the Western and Eastern Fronts.

Keeping an army alive

British officers at Suvla Bay ‘taking tea’.

Something desperate had to be done. A British-led make-or-break offensive was planned all along the Allied lines in the Dardanelles. A major flanking assault was planned at Suvla Bay, in the north. It was to be another attack from the sea intended to support a breakout from the Anzac sector, eight kilometres to the south.

The Turks only had minimal forces at Suvla Bay and should have been quickly overwhelmed, but the landing was spectacularly mismanaged. The British commander was elderly, nervous and totally inexperienced in such operations. In fact his performance was later described as one of the most incompetent feats of generalship in the First World War. After a week of indecision and inactivity which led to the British infantry sitting on the beach awaiting orders to advance, he was dismissed but it was too late. The Turks rapidly reinforced the hills, and soon this sector was bogged down in a stalemate just like the Anzac and Cape Helles sectors. The new commanders could not see an easy solution now that the element of surprise had been thrown away.

The Suvla Bay force would remain on the beaches until finally the High Command finally decided that retreat from the Dardanelles was the only viable option. But in the interim, it needed to be kept alive. One key problem was that of logistics. The beaches of Suvla Bay were shelving sand, which meant that supplies and ammunition had to be rowed ashore under fire from the Turkish artillery in the hills above. Casualty evacuation was just as awkward.

Proper wharfing was a priority, and the few little rocky bays like the one at West Beach had to be quickly turned into small docklands. West Beach and its adjacent cove, subsequently to be known as Kangaroo Beach, was where the Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train would make its admirable mark, building the much needed wharfs in conjunction with the British Army engineers.

Why a ‘bridging train’?

What to do with all these stores?

In the early stages of the war, many of the 8,000 Australian naval reservists were not trained suitably to serve on board ships in the RAN. So most reservists found themselves doing odd jobs like guarding the wharfs, practicing minesweeping, watching out for saboteurs and a myriad of other odd jobs and minor duties.

Then someone hit on a good idea. Since the reservists were capable of sailing about in small boats, and had some technical training, they should be able to operate pontoon bridging trains. So off some of them went to war at the other side of the world — at Suvla Bay.

Bridging trains were wagon-loads of prefabricated bridges, made up of small boats topped with planking that were assembled on the battlefield to span rivers. These were needed urgently by the Allied Armies which was running short of engineers to do the work. It seemed like work that navy men could do, so the 1st RANBT unit was formed in Melbourne in February 1915 and a select band of three hundred or so volunteer reservists found themselves with a new career. Some had some maritime and labouring backgrounds, but they came from all walks of life, including an architect, a dentist and a pearl-diver.

These pontoon bridges were carried into action on horse-drawn vehicles, so these sailors found themselves being given crash-courses in horsemanship, engineering and pontoon bridging, while swapping their naval uniforms for cavalry khaki.

Advanced technical training in Australia was a problem due to lack of equipment and expertise. So the RANBT was loaded on to ships in late May 1915 with the assurance that they could learn more effectively in training camps in England.

So when these men finally set off, they thought that they were bound for the Western Front. However, they were off-loaded in Egypt like the rest of the Anzacs. The RANBT was sent to reinforce the stalled invasion force at Suvla Bay.

Neither army nor navy

Building a ‘crib’ for wharf foundations

But when they arrived nobody seemed to either own them or be willing to take responsibility for feeding and accommodating them. They were not part of the Anzac Army. They were not Royal Navy. It was a matter of finding something for them to do.

Early on the morning of 7th August the RANBT landed at Suvla Bay under accurate Turkish artillery fire. The Australian sailors immediately set about building a pontoon pier to enable desperately needed supplies to be brought ashore, and casualties to be evacuated. This was their first vital contribution amid the shambles of the ill-planned and poorly led campaign. The RANBT set up their camp in a little cove that became known as Kangaroo Beach, just around from the main harbour at West Beach. This was where they worked on an incredibly diverse variety of tasks.

Over the coming months they built wharfs and piers. They unloaded the work-boats that used them. They repaired the wharfs and piers when storms tore them apart, or the Turks blew them up, or when over-excited or careless coxswains crashed their vessels into them. Ingenuity was the key. They repaired and stock-piled engineering equipment that might otherwise have been discarded. They cobbled together whatever was needed in their open-air workshops on the beach. They did all the assorted jobs that the Royal Navy and the British Army were ill-equipped or reluctant to do.

It was fortunate that the man appointed to command this unusual unit was an intelligent and resourceful character. Lieutenant-Commander Leighton Seymour Bracegirdle was ideally suited to the RANBT. He was an inner-city lad from Sydney who craved adventure, had seen service as a midshipman with the New South Wales Naval Brigade during the Boxer rebellion in China in 1900, and ridden with the South African Irregular Horse in the Boer War. He had returned wounded to Australia, and after an unsatisfying spell as a clerk, swapped from the Naval Reserve to join the brand-new RAN in August 1914. He served as a staff officer with the joint naval-army expedition that captured the German colonies in New Guinea and nearby Pacific islands. He was with this force until it was disbanded in February 1915, and was then appointed commander of the 1st Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train.

The senior officers lived well, out on the battleships on the bay, with table linen, four course meals and stewards to serve them. But on shore it was a very different story. On the beach, stores were piled everywhere, ration boxes filled with tinned, pickled or bottled supplies, and except for the rum and tea, universally loathed. Corned beef that turned liquid in the heat, tooth-breaking biscuits smothered with apricot and plum jam, flies in every mouthful, and very rarely anything fresh.

West Beach was under continual surveillance by the Turks and within easy range of their long distance artillery, so shelling was a daily event. The bonus was that when shells burst near the docks, they stunned the fish that swarmed in the shallows. The Australians shocked the British officers by stripping off and salvaging the fresh fish for their menu.

Black beetle barges

The rust red barges and the Nile barge to their left were nowhere near as useful as the ‘black beetles’.

While the invasion force had barges as cargo carriers, these had to be towed. So did the Nile barges obtained from Egypt. An invasion like this meant that self-propelled barges would be essential. Lord Fisher, part architect of the Dardanelles campaign (and the man who had cautioned Churchill that it could not succeed without putting an invasion force ashore to neutralise the Turkish forts) had realised that they would need specialised landing craft. Ships’ lifeboats and barges were certainly insufficient to keep up the massive daily consumption of water, food, ammunition and supplies in general that the invading army, once ashore, would need.

No one had realised how long the campaign would continue, so Fisher’s foresight proved invaluable. Back in February two hundred steam-powered landing craft were commissioned for the Gallipoli campaign. They would be called “X” lighters. Pollock drew up preliminary plans in just four days, showing long motor-driven barges with spoon-shaped bows that could be easily run up on to beaches, and they were equipped with drop-down ramps to facilitate unloading. The men at the Dardanelles soon called them ‘black beetles’ because the ramps looked like the antennae of stag beetles. They did the job but guaranteed instant seasickness in any sort of swell.

Problem solvers

A good example of the RAN Bridging Train’s ability was to tackle any problem was in the supply of fresh water. There were 80,000 men at Suvla Bay and water needed to be shipped in from places as far away as Egypt. Once it arrived, it sat out in the bay on the transport ships, and had to be transferred to water lighters, and then transferred into small containers like empty petrol tins. These were painted green to distinguish them from the lethal red ones.

A good example of the RAN Bridging Train’s ability was to tackle any problem was in the supply of fresh water. There were 80,000 men at Suvla Bay and water needed to be shipped in from places as far away as Egypt. Once it arrived, it sat out in the bay on the transport ships, and had to be transferred to water lighters, and then transferred into small containers like empty petrol tins. These were painted green to distinguish them from the lethal red ones.

These tins were then tracked away on the mules of the Indian Transport Corps. The groups of thirsty British soldiers and sailors gathered around the water distribution points and made excellent targets for the Turkish artillery. The RANBT, in true Australian fashion, ‘borrowed’ fire hoses and their pressure pumps from the warships and set up a faster and safer way of distribution. They were instrumental in designing pumping and piping systems for getting vital water supplies ashore from the ill-designed lighters, and the British Army and Navy were only too glad to hand over the responsibility to this curious little unit of Australian naval men.

A daring escape

Lord Kitchener, Britain’s secretary of State for War visited the Dardanelles himself, saw how hopeless it was, and by mid November, recommended evacuation. The British Government was not happy, prevaricated for a couple of weeks, then faced the inevitable. Now they were faced with how get 105,000 men and 300 guns safely away before the Turks realised what was happening, and wiped them out.

Lord Kitchener, Britain’s secretary of State for War visited the Dardanelles himself, saw how hopeless it was, and by mid November, recommended evacuation. The British Government was not happy, prevaricated for a couple of weeks, then faced the inevitable. Now they were faced with how get 105,000 men and 300 guns safely away before the Turks realised what was happening, and wiped them out.

Painstaking efforts were made to make the Turks think that the British were building up for another offensive rather than a withdrawal. Just before the evacuation the RANBT built wharfs as pre-fabricated units on the beach, in full sight of the Turks up on the hills. But the Turks assumed they were designed for landing more troops. Once built, they were shipped into locations that were out of sight from the Turkish positions. Certainly, the Turks had not realised that the Allies were abandoning the Dardanelles, and were planning to leave by night, in secret.

The men of the RANBT were instrumental in building the piers that allowed the evacuation in mid-December – which proved to be the most successful part of the whole tragic Gallipoli campaign.

– Geoff Barnes & Stephen Gapps