Yvonne Gregory, by Bertram Park, 1919. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, London.

The museum’s current exhibition War at Sea – The Navy in WWI includes several examples of dazzle camouflage—the (mostly black and white) patterning used by ships to disguise their outline and heading. Perhaps it is because I have been immersed in WWI dazzle research, but it seems to me that the same sort of black and white patterning is everywhere I go around Sydney at the moment.You may have noticed black and white is back in women’s fashion. It is often seen in stripes, but also dazzle-like zigzags. Black and white schemes are painted on cars, on shop fronts, and cafes. Is this merely coincidence? Or is there in fact an historical relationship between dazzle boats of WWI and contemporary art and fashion?

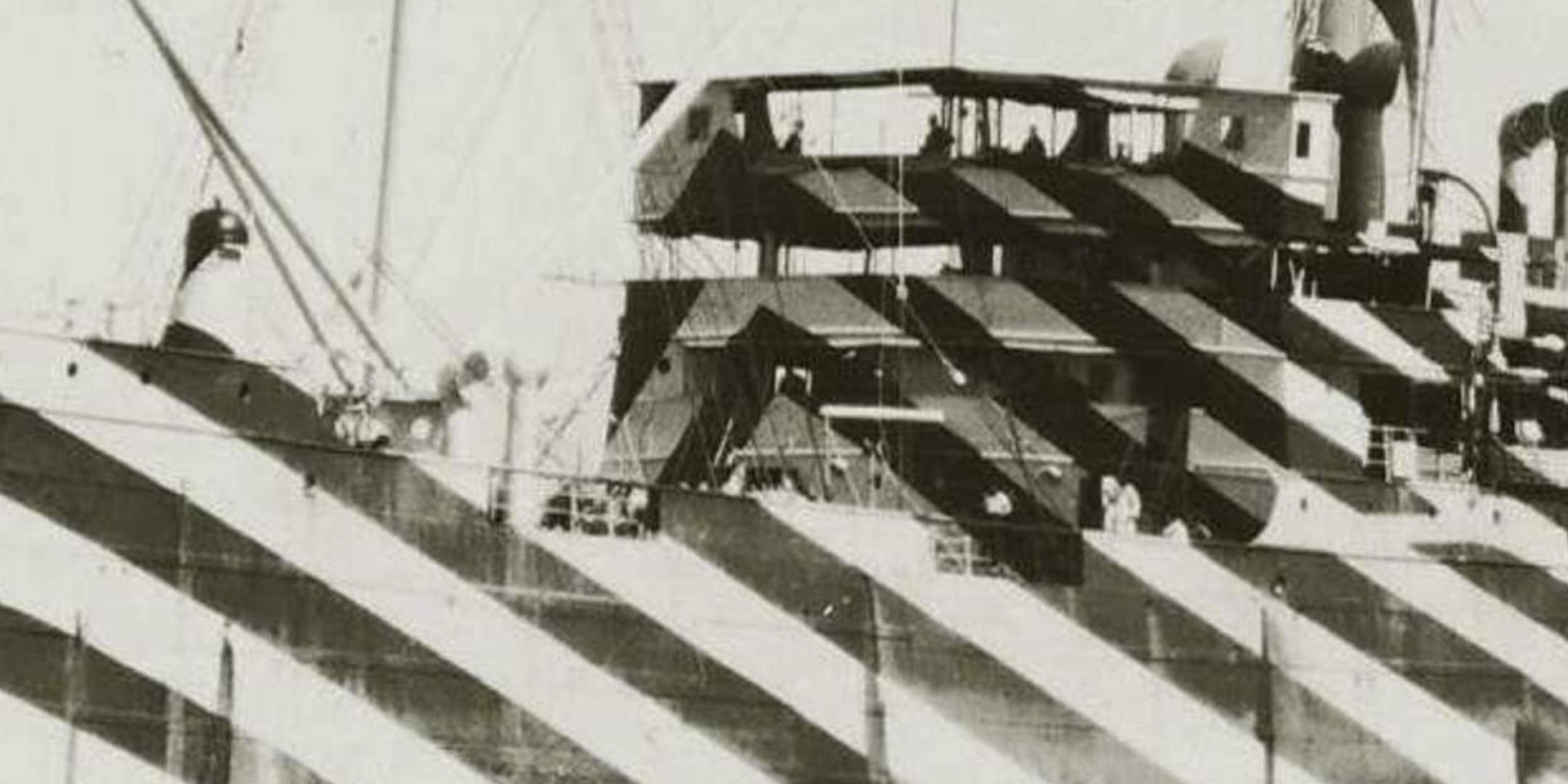

Towards the end of World War I large numbers of merchant ships were brightly painted in often bizarre geometric patterns known as ‘dazzle painting’, later known as dazzle camouflage. The aim was to thwart German U-boat (submarine) captains who had been destroying large amounts of shipping. Such eye-catching designs weren’t really camouflage. The colour scheme was designed to confuse and deceive an enemy looking at a ship’s waterline through a periscope as to the vessel’s size, outline, course and speed. This was done by painting ships’ sides and upperworks in contrasting colours and shapes arranged in irregular patterns. When you look at some of the crazy lines created in these schemes as they appear on waterline ship models (the same wood-block models used during World War I to test dazzle patterns), you can get an idea of how it worked. Some of the illusions make it very difficult to tell which end of the ship is which, or whether there are two ships side by side.

A waterline 1:600 scale model recreating similar models used in World War I to test dazzle schemes as viewed from a periscope. By ANMM volunteer modelmaker Col Gibson.

The idea, in essence, was to confuse U-boat captains by making it difficult to plot accurately an enemy ship’s movements when manoeuvring for an attack, causing the torpedo to be misdirected or the attack to be aborted. It made it awfully difficult for submarine commanders to consult the information and sillouhette outlines in the 1914 edition of Jane’s All the World’s Fighting Ships to determine what the vessel was, what speed it might be doing, whether it was armed, a merchant ship or perhaps a warship with anti-submarine capability and something to be avoided.

So how did dazzle ‘camouflage’ end up as a fashion statement? Fashion has a long and close connection with military dress. In the 18th and 19th century the ‘cut and dash’ of uniforms was a recruiting attraction. Civilian dress often mimicked the military, though the introduction of a more drab khaki by World War I interrupted this trend. But with intriguing camouflage patterns extending from military hardware into uniforms by the 1930s, military fashion was back. In recent years the military look has been a well-spring for fashion to draw upon—from street wear to suits, from Stussy to Gucci, ‘camo’ has become almost ubiquitous.

The key to the connection between dazzle and fashion was art. Cubist paintings by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque had appeared just before World War I and the manner in which Cubism distorted its subjects influenced military camouflage. On seeing a camouflaged artillery piece in the streets of Paris early in the war, Picasso was heard to remark, ‘It is we that have created that’.

The rush to camouflage and dazzle military equipment offered the opportunity for some artists to put forward their skills toward the war effort as ‘camouflage painters’, rather than soldiers. The first section of French camouflage painters was formed in 1915 and their technique became known as zebrage because of its resemblance to zebra stripes. The unit’s commander, artist Lucien de Scevola ackowledged the influence of cubist paintings in their efforts to ‘dissimulate things’. He noted that ‘In order to deform totally the aspect of an object, I had to employ the means that cubists use to represent’.

‘The newest things in bathing suits brighten the beach at Margate, England. The “dazzle” designs of gayest hue defeat the usual purpose of camouflage, that of promoting low visibility’. New York Tribune June 15 1919

A dazzle paint scheme on large ships that had once been monotonous grey or black was indeed striking. And it fitted with a changing sense of modern art and style. Even before World War I was over, dazzle pattern schemes appeared in women’s fashion. At first, they mimicked the dazzle ships so familiar in harbours around the world. British and North American bathing costumes began to appear in dazzle patterns. By April 1918 conservative Australian newspapers were ridiculing this ‘sartorial disaster’. In a presage of 1920s exuberence and enchantment with the modern, dazzle seemed not only to represent this new age of modernity, but to be a celebratory distraction from the Great War.

On 12 March 1919, the Chelsea Arts Club held a costume party, called a Dazzle Ball, at the Royal Albert Hall in London. A journalist from The Independent newspaper was not greatly impressed with the connections between camouflage, fashion and art:

Four British naval officers, distinguished for their success at camouflage, had charge of designing the dresses, and the ballroom looked like the Grant Fleet with all its warpaint on, ready for action. The jazz bands produced sounds that have the same effect upon the ear as this “disruptive coloration” has upon the eye.

Who could have thought a dozen years ago, when the Secessionists began to secede and the Cubists began to cube, that soon all governments would be subsidizing this new form of art to the extent of millions a year? People laughed at them in those days, said they were crazy and were wasting their time, but as soon as the submarines got into action, the country called for the man who could make a dreadnaught look like “A Nude Descending a Staircase”…The submerged Hun with his eye glued to the periscope could not tell whether it was a battleship or a Post-Impressionist picture bearing down upon him…

Sydney followed London’s lead and in October 1919 a fundraising ‘Dazzle Ball’ was held at Sydney Town Hall. The Sunday Times reported that:

The Town Hall certainly was a scene of dazzling bewilderment, and the eyes of onlookers ached the following day from the effort of focussing on the fancifull-clad dancers through the thick downpour of moving, multi-colored paper streamers that showered over the main hall. The scene was bizarre and wonderful beyond anything ever attempted here.

The connections between modern art and dazzle were not lost on commentators. The Perth Daily News noted in October 1918 that:

… under the title of ‘camouflage,’ an orgy of mad and frenzied coloring which Marinetti and his faithful band of Futurists would have looked at in silent awe crawled over everything. Tanks and guns vanished; lorries were swallowed up; aeroplane hangars faded away; even the grey transports on the sea disappeared. Strange shapes, painted a thousand different ways in a thousand different tints, alone remained.

People lamented that the end of the war would cause the disappearance of dazzle. In September 1919 the Sydney Morning Herald noted that:

While everyone rejoices in the removal of the occasion for dazzle painting, there are some who regret the latter’s disappearance. It produced an effect resembling a crazy dream from “Alice In Wonderland,” but it gave a touch of variety and picturesqueness now lacking in shipping. To see a great liner in her camouflage was to be reminded of a very dignified and imposing lady reluctantly masquerading at a fancy dress ball in a fantastic futurist costume.

In Britain, marine painter Norman Wilkinson led the charge in devising dazzle ship-painting schemes in desperate attempts to halt the incredible shipping losses from 1917—when 20 British ships were being sunk per week. One of Wilkinson’s dock painters was Edward Wadsworth, the leading British exponent of Vorticism—a blend of Cubism and Futurism. His dramatic 1919 oil painting Dazzle-Ships in Drydock at Liverpool (above) came to symbolise the connection between dazzle and art.

Edward Wadsworth ‘Dazzle-Ships in Drydock at Liverpool’

Oil painting, 1919 National Gallery of Canada

Dazzle was taken to a new level in fashion with ‘society photographer’ Bertram Park’s amazing 1919 image of Yvonne Gregory in dazzle costume with a dazzle backdrop.

In the United States, dazzle also became important during World War I. The Americans called it ‘jazz painting’. The leading exponent was Everett Warner, who became a professor of art at the Carnegie Institute after the war. Warner also headed up US dazzle painting in World War II. Interestingly, one of his students in the 1940s was a young Andy Warhol. It’s not difficult to see a trajectory between Wadsworth, Warner and Warhol.

Yvonne Gregory, by Bertram Park, 1919. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, London.

Not only have artists been critical to the development of camouflage techniques for military purposes during the 20th century, but they have become increasingly interested in them as art. At the end of World War I, writer Gertrude Stein noted that when she drove out to see the devastation of the front lines, she came across camouflage from various nationalities. The idea was the same, but the technique different bewteen German, French, British and American:

… the colour schemes were different, the designs were different, the way of placing them was different … it made plain the whole theory of art and its inevitability.

Dazzle, disruptive patterning and true camouflage continued to influence art through the 20th century. French artist Alain Jacquet produced a large body of camouflage-influenced work 25 years before Andy Warhol’s better known 1986 Camouflage series. Jacquet found camouflage to be a paring back of representation, of ‘going inside it’ and ‘breaking reality into dots’. He found camouflage to be a ‘new way of seeing’.

Artists were implicit in the military project of dazzle, but also in undermining it. While dazzle as fashion and art draws a wonderful picture of sharp, contrasting design so different to previous senses of patterning, it overlays a more sinister truth – that dazzle was born in war. In the 1980s American artist Marilyn Lysohir created a large ceramic model of a WWII battleship painted in multi-coloured dazzle. As Lysohir noted, ‘the seductive qualities [of dazzle] are juxtaposed against the destructive traumas of war.’

Andy Warhol famously found camouflage patterning the perfect medium to represent a lack of focal point and hierarchy in shape, as well as no pictorial depth or vanishing point. Wilkinson and Wadsworth would have agreed—this was just what the World War I dazzle artists were seeking too, albeit for very different reasons.

In 2014 artist Carlos Cruz-Diez worked with the idea of dazzle using the Merseyside Maritime Museum’s Edmund Gardner pilot ship

Dazzle continues to inspire artists 100 years on from World War I. Perhaps we could take up the lament at losing the amazing sight of dazzle painted ships after WWI and add something to the mix of WWI centenary imagery by dazzling up a vessel on Sydney Harbour, like this one at the Merseyside Maritime Museum.

— Dr Stephen Gapps, Curator

Further reading:

Hardy Blechman Disruptive Pattern Material—An Encyclopedia of Camouflage Firefly Books, Ontario and New York, 2004.

For an online exhibition of images of World War I dazzle ships visit the Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool, UK.

Camoupedia – A blog for clarifying and continuing the findings that were published in Camoupedia: A Compendium of Research on Art, Architecture and Camouflage, by Roy R. Behrens (Bobolink Books, 2009).