As the sun rose over Sydney Harbour on Empire Day 1914, two sinister-looking, cigar-shaped vessels glided along behind their escort vessel HMAS Sydney. The radiant May sunshine glinted on the grey steel of the vessels that sat only a few feet above the water. Noone had seen anything like these craft in Australian waters. The first two submarines of the new Australian navy had arrived.

In October 2013 Sydney Harbour saw a grand celebration for the 100th anniversary of the arrival of the other elements of the new Royal Australian Navy – the warships. But on the 24th of May this year, 100 years to the day of the RAN’s first submarine arrival, there will be little fanfare.

So too in 1914 – apart from a handful of vessels escorting them – there was little fanfare. Submarines AE1 and AE2 had serendipitously arrived on the 24th of May – Empire Day. They had missed the opportunity of the grand entry of the new fleet the previous October. After a voyage of 80 days from Britain and with quite a few mishaps and delays, the submarines just happened to arrive on what was a signficant commemorative holiday in Australia.

Even though the submarine arrival was relatively subdued, they did create some interest. During the day, as they lay moored at Garden Island naval base, the submarines were a curious attraction for crowds gravitating to the harbour foreshores after attending Empire Day celebrations.

The significance of Empire Day has now been lost. It was established to honour the long reign of Queen Victoria after her death in 1901 and was celebrated each year throughout the British Empire on 24 May, the day of her birth. Flags were flown on all public and many private buildings and there were receptions and gatherings with speeches, street marches and parades, as well as bonfires and fireworks at night. It waned after the Second World War as people associated it with Cracker Night and a day off, rather than a celebration of ties with the pinnacle of British Empire under Queen Victoria’s reign.

One can understand why. On Empire Day in 1914 the Archbishop of Sydney Dr. Wright pronounced in his sermon ‘Lesson in loyalty’ that;

On this Sunday, we think of the Empire. The day is dedicated to the Empire, and we deliberately pledge ourselves to do our duty for the Empire. In Australia we have six millions of people, but looking down upon us are a thousand millions of coloured people, and our position would indeed be precarious were it not for the Empire.

Empire Day was avidly celebrated throughout Australia from 1907. State Library NSW

By the 1950s and the beginning of the dismantling of the White Australia Policy – as well as a period of de-colonisation around the globe – the concept of Empire was in decay. In 1958 it was renamed the more palatable Commonwealth Day and moved in 1966 from the initial date – Queen Victoria’s birthday – to 11 June, Queen Elizabeth II’s birthday. it was more commonly known as Cracker Night and celebrated by bonfires and the lighting of fireworks. It’s now our ‘June long weekend’ we all look forward to.

But in 1914 the enthusiasm for celebrating the fact Australia was still part of the British Empire was arguably at its height. Empire Day was observed in state schools from 1905 with speeches, pageants and songs. School children would wear patriotic costumes and participate in a ceremony swearing an oath of allegiance ‘to King and Empire’.

Australians had broken some bonds of British colonialism, but were very much concerned with seeing the Federated nation at once independent and also tied to Britain. And Australia’s political strategists were advocating and planning for a venture into its own form of Empire building – dividing the potential conquest of German Pacific colonies between Australia and New Zealand in the event of war with Germany.

The fact that from 1913 Australia now had a new and powerful navy gave substance to these ambitions. And on Empire day 1914, the final element in the Royal Australian Navy’s fleet had arrived – submarines.

When the cruisers and destroyers of the fleet made their grand entrance into Sydney Harbour on October 4 1913, there was much to celebrate. They were a visceral expression that the power of the British Navy was also Australian. Battleships were imposing things. They created a spectacle that drew tens of thousands of Australians to view the awe-inspiring dramatic scale of these modern warships – particularly the battle cruiser HMAS Australia.

Postcard showing HMAS Australia and the vessel’s specifications. ANMM Collection

But the submarines were different. After initial excitement in the build up to their arrival, news reports of AE1 and AE2 entering Sydney are laconic, bemoaning the fact there was not a great deal to see of a submarine, and that it was also impossible for journalists to board them and see what was inside – that was still top secret information. One journalist noted that the only civilian to have seen inside a submarine was the head of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.

Still, as Stoker Petty Officer on AE2 Henry Kinder noted in his memoir ‘naturally the submarines were objects of curiosity, and crowds of people used to sit and watch them from Mrs Macquarie’s Chair.’

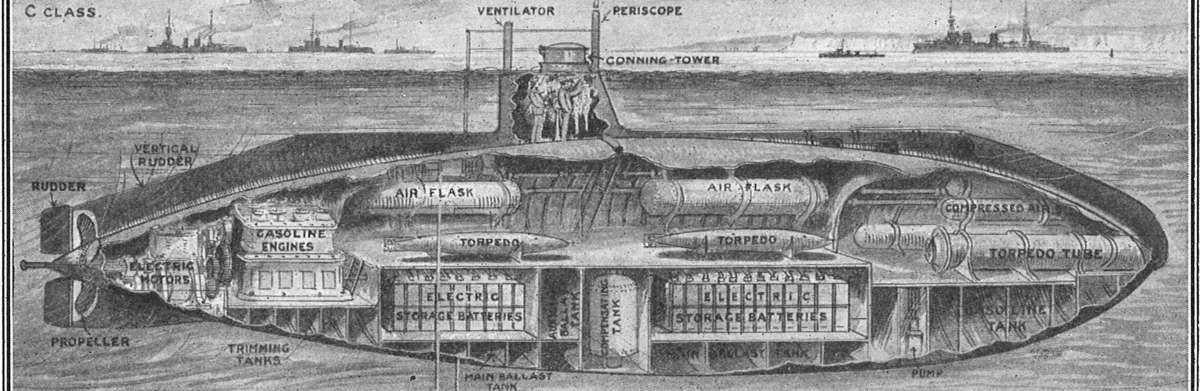

Observers of the submarines in Sydney Harbour struggled to describe them. Submarines were objects of pure function. Their form followed the best way for a submerged vessel to manouvre and fire torpedoes. They were, much like the tank was to become on the battlefields of Europe, a radical development in a new, highly industrial form of warfare. What was even more sinister was that they could travel unseen and undetected under water.

This cutaway view of a C Class submarine, precursor of the E Class vessels purchased from Britain by the RAN, shows little consideration for the crew. ANMM Collection

Submarines were not ‘gentlemen of war’. When the Royal Navy first adopted submarine technology in 1901, Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson famously described them as ‘underwater, underhand and damned un-English’. Wilson went even further to suggest that Britain should ‘… treat all submarines as pirates in wartime’ and they should ‘hang all crews’.

But after other navies began to take up submarine development, the British were forced to as well – the potential of one undetected submarine to destroy a battleship with one good torpedo shot was not lost on the Royal Navy.

Neither was it lost on the Australian navy. Despite initial misgivings about the relevance of submarines to Australian conditions by commander of the Commonwealth Naval Forces William Rooke Creswell, the rapid development of submarines in other navies including Germany from 1907 saw the RAN not wanting to miss out, and support grew for the purchase of two British submarines of the latest E Class.

AE1 preparing to be towed. ANMM Collection

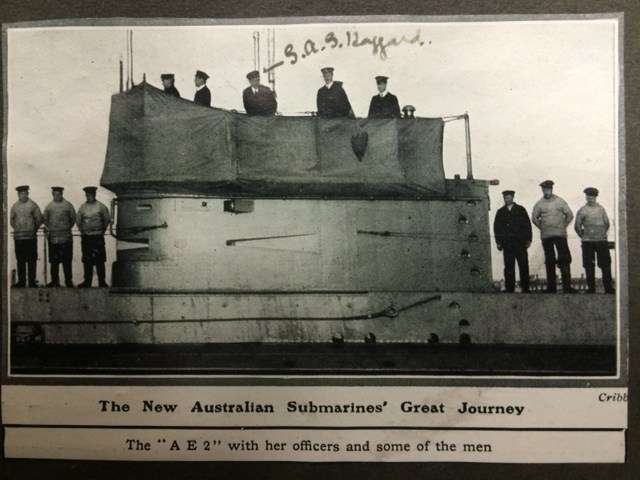

The submarines were constructed by Vickers Armstrong at Barrow-in-Firness in England from November 1911 and launched in May and June of 1913 – too late to make the grand arrival of the rest of the Australian Fleet in October that year. Under the command of RN Lieutenants Henry Hugh Gordon Dacre Stoker (AE2) and Thomas Besant (AE1) they travelled 13,000-nautical-mile (24,000 kms) to Sydney, at the time ‘the longest submarine transit in history’, with 60 of the 83 days of the voyage spent at sea.

When the submarines arrived off the northern coastline of Australia, they caused a stir. Commander Stoker in his 1925 book Straws in the Wind noted how Aboriginal people at Port Darwin compared HMAS Sydney (escorting AE1 and AE2) to a mother emu with two chicks following behind. In New Guinea, when the submarines joined the expeditionery force against German Pacific colonies, Stoker described how New Guineans were taken aback when the submarine dived and then re-surfaced. He reported that they called them ‘Devil fish’.

What was common to observations of the submarines in 1914 was an uneasy realisation that the nature of navies and naval warfare had changed forever. The submarines were in fact an indicator of a new modern warfare that was about to be unleashed around the world in defence of empires. The ‘Devil fish’ that arrived on Empire Day in 1914 presaged the changing nature of war at sea during the Great War. But few people were to note this of a war that was meant to be ‘over by Christmas’.

Newspaper clipping with a photograph of the AE2 crew on deck. ANMM Collection