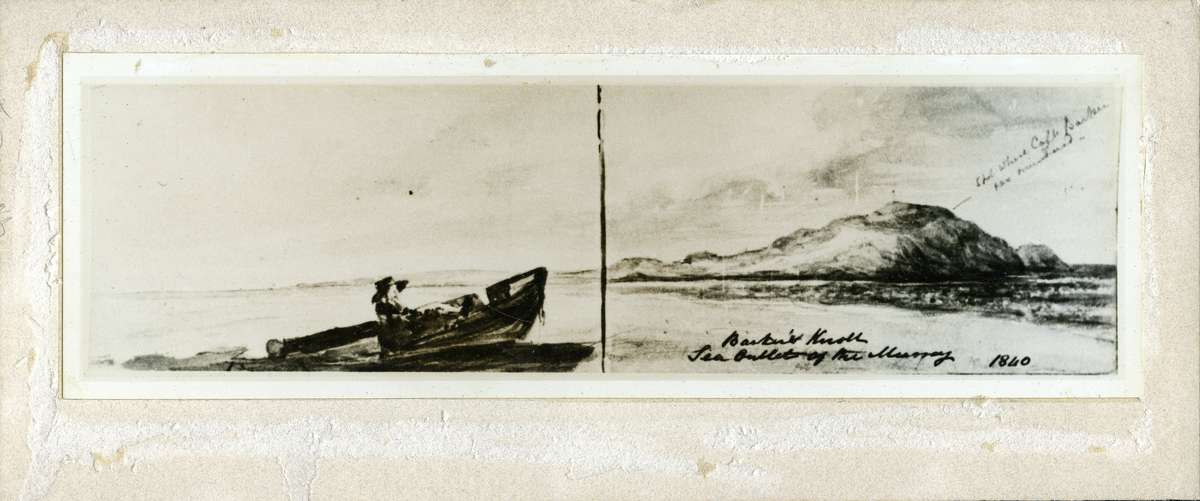

Barkers Knoll, sea outlet of the Murray 1840.

ANMM Collection

In Australia’s past, there were many unsung heroes whose quiet achievements deserve to be remembered, and it is often only by chance that they are brought to light. I recently came across a simple sketch of a remote and windswept piece of coastline in South Australia, and would have continued reading if I had not noticed the handwritten note on the top, “Spot where Captain Barker was murdered”. Although the area, particularly nearby Kangaroo Island, had been sporadically used by sealers since the mid 1700s, there was no settlement there in 1831 when Captain Barker visited. It seemed an unusual place for a murder to happen. As it turned out, not only was it a most unlikely location but Captain Barker was a most unlikely victim.

Captain Collet Barker was an enthusiastic lieutenant from England when he was appointed the commandant of the settlement at Fort Wellington on Raffles Bay, Northern Territory, in 1828. This struggling and isolated settlement had been created in the hope of fostering sea trade with Malaysia, as well as protecting Australia’s north. The isolated outpost faced a host of problems from the beginning, not least of which was the unsuitability of its earlier commandants. Unsupported and ill-equipped to deal with such an extreme social and physical situation, their leadership was inept and their interactions with the local Indigenous population brought tragic consequences. By the time Barker arrived, tensions had escalated. An Indigenous woman and child had been killed and a young girl had been taken to the settlement as a hostage. Illness and low morale were rife, and the mix of convicts and bored militia was toxic.

Undeterred, a determined Barker took on the challenge. His positive influence was felt throughout the small colony on every level, shown especially in his sensitivity in dealing with the local Indigenous population. So good did relations become, that within a year Barker was able to accompany a local hunting group alone and unarmed on a four day journey along the coast. He had genuine respect for and interest in the group and believed that most of the problems had been due to the attitudes of the colony. This opinion of course was contrary to most of those prevailing at the time and yet the positive results of his humane and enlightened approach did not go unnoticed.

In 1829 Fort Wellington was abandoned and Captain Barker was ordered by Governor Darling to return to Sydney aboard the Isabella. Darling had plans for Barker to be sent to New Zealand where European settlements were struggling with the Maori inhabitants. Before that however Barker was ordered to stop near Albany, South Australia, and confirm the location of the entry to the sea of the Murray River. And that is why in 1831, Barker found himself ashore with a small crew on this still very remote coast.

From accounts of people who were there on April 30 when Barker’s exploring party arrived at the Murray River outlet, Barker decided to cross it alone, clad only in his underwear. An eyewitness version tells of his last sighting: He “fastened his compass on his head, he plunged into the water, and with difficulty gained the other side; to effect which took him nine minutes and fifty-eight seconds. His anxious comrades saw him ascend the hillock and take several bearings; he then descended the farther side, and was never seen by them again”.

“Sea outlet of the Murray from the beach below Barker’s Knoll, where that fine fellow Barker was murdered”.

ANMM Collection

It was later discovered through interpreters that Barker had been attacked and killed by three local Ngarrindjeri. In what was a tragic case of misunderstanding and mistaken identity, it is believed that his death was in retaliation for the harsh and brutal treatment inflicted upon the Ngarrindjeri by the sealers who had been frequenting the area. The irony was that Captain Barker was one of the very few of the earliest Europeans who had sincerely tried to understand local customs and practices. It may well be that his confidence and goodwill had overcome caution as he approached the Ngarrindjeri men with his metal compass in his hand on the beach that day. It is likely he had been unaware of the terrible atrocities that the sealers had been dealing out.

Barker’s death was a blow to the colony. He was remembered as someone who was “honorable and just in private life, a lover and follower of science, indefatigable and dauntless in his pursuits, a steady friend and entertaining companion, charitable, kind hearted, disinterested and sincere”.

We cannot know what positive influence Barker’s beliefs may have had on future European and Indigenous relations, or indeed whether he would have had any success in persuading others that respect and understanding were possible and would be of great benefit to the settlement. What we can know is that he was an enlightened man who was ahead of his time in many ways. Barker is remembered by Mount Barker in South Australia, and by a memorial to him in St. James’s Church, Sydney.

Myffanwy Bryant