‘Australian pirate tales’, by curator Dr Stephen Gapps. From Signals 97 (Dec 2011-Feb 2012).

We might not think of Australian history as having much to do with pirates. Yet from the infamous Batavia mutiny in 1629 to the 1998 seizure of the oil tanker Petro Ranger by pirates in the South China Sea, there have in fact been dozens of instances of piracy in Australian waters or on vessels travelling from these shores.

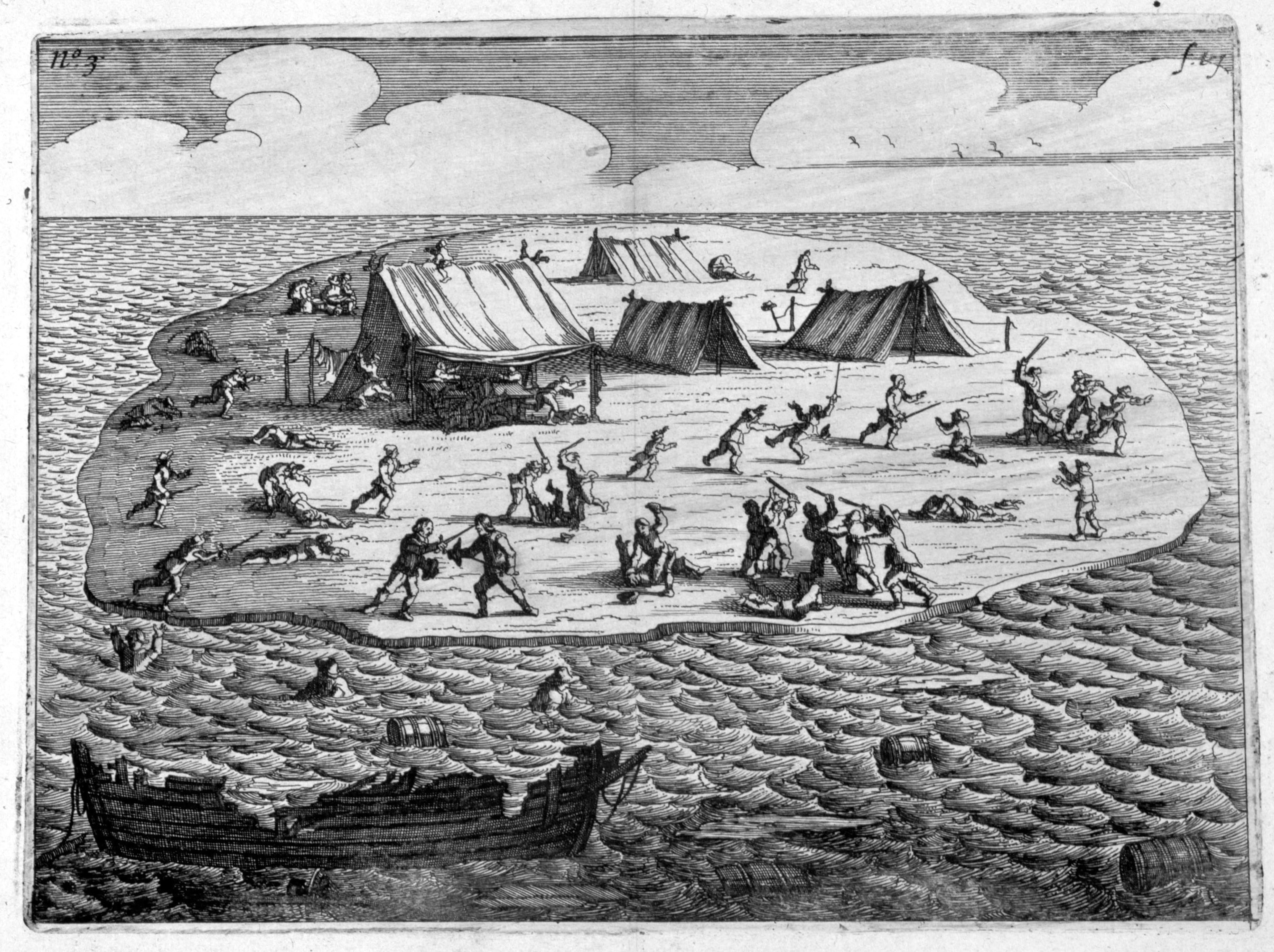

The Batavia Massacre

In 1806 the brig Venus was weather-bound for five weeks in Twofold Bay, on the south coast of New South Wales. Ill feeling had been building between its crew and Captain Chase who, fearing for his life, left to report to the authorities that he also feared the crew would take the ship – which they promptly did. The Sydney Gazette described the ‘band of ruffians’. First mate Benjamin Kelly was a ‘pockmarked’ American whaler. Second mate Richard Edwards had a ‘very remarkable scar or cut in one cheek’. Seaman Joseph Redmonds was a ‘mulatto’ who wore his hair in pigtails and had ‘holes in his ears, being accustomed to wear large earrings’. Their accomplices included a ‘Malay cook’, two convicts with ‘sallow complexions’ and a woman with a ‘hoarse voice’. They would have been at home in any pirate tale.

The incredible voyage of Mary Bryant and her convict companions from Sydney to Timor in an open boat in 1791 showed that escape by boat from the colonies was indeed possible. William Bligh’s epic open-boat voyage after the 1789 Bounty mutiny may also have inspired the many convict escape attempts that followed. Certainly, after the mutiny on the Bounty, ship captains in the Pacific were on their guard. The lure of stealing a ship and living in a tropical paradise in the South Seas was clear. Lieutenant George Tobin, on Bligh’s second breadfruit voyage in 1792, noted how ‘passing some months at a South Sea Island and in the full swing of indulgencies’ was good reason to keep a ‘vigilant eye upon the crew’.

Bligh at Timor

‘Piratical seizure’ of ships became a major headache for colonial authorities, and strict harbour regulations were instituted. After the establishment of Newcastle to Sydney’s north in 1804, ship security was critical. Vessel arrivals and departures required official sanction, and no one could leave a vessel without permission. Crews had to be on board their ships by 8.00 pm and sentries guarded the wharves. Despite these measures, many escapes were made from Newcastle. In 1804 convicts made off with Sergeant Day’s boat. In 1806 six convicts escaped on another unnamed boat. In 1814 the schooner Speedwell was taken by four ‘desperadoes’. The Newcastle pilot boat was taken in 1820 and the sloop Eclipse in 1825. None of these pirated vessels was ever heard of again.

During the early 1800s an average of one vessel was taken by pirates every year. In 1813 a vessel called Unity was ‘piratically seized’ by convicts while moored in the Derwent River off Hobart Town. Seven armed men crept aboard at night and cut the moorings, landing the crew in a small boat and then setting sail. In 1816 the brig Trial was ‘piratically seized’ in Sydney Harbour by a ‘banditti of villains’, mostly convicts employed in the stonemasons gang working on the Macquarie light tower, as well as two ‘natives of Portugal’.

A Government Notice in 1817 described the ‘Piratical seizure of the William Cossar’, a government vessel ‘cut from her moorings by some Pirates’. One was described as ‘a gypsy’ with ‘dark complexion, black eyes, black hair’ and the ‘fore finger of [his] right hand missing.’ But as the two-masted, 20-ton William Cossar had neither decks nor anchor, it was presumed by the Sydney Gazette that its ‘destruction was inevitable’. In fact neither it nor Unity were ever seen again. The wreck of the Trial was later discovered at South West Rocks, but none of the convict escapees were found.

Hobart Town

If there was ever a scourge of piracy in Australian history, it was in Tasmania during the 1820s to 1850s, when Van Diemen’s Land was the repository of the largest number, and many of the most hardened and desperate, of convicts in the colonies. ‘Piratical seizure’ was so prevalent that there was a standing Port Order to Derwent shipping that ‘when moored… sails must be taken off the spars and the ship’s rudder taken ashore’.

In the Australian colonies the term ‘pirate’ was selectively applied, often to highlight particularly bold or bloody crimes at sea. The so-called ‘pirates of the brig Cyprus’ were a case in point. In August 1829 Cyprus was transporting a group of convicts from Hobart to Macquarie Harbour when it was storm-bound in Recherche Bay. The convicts took over the ship, which was stocked with provisions, and marooned 44 soldiers, sailors and convicts who chose not to join them. They then set about renaming and repainting the vessel. They cut off the figurehead and forged a set of ship’s papers and a false log of a voyage from Manila to South America. In a remarkable feat of navigation with no experienced crew, ‘Captain’ Swallow sailed the Cyprus to New Zealand, the Chatham Islands, north-east to Tahiti and then to Tonga. The crew were divided about where best to escape the authorities – in the Friendly Isles of Tonga or further away from New South Wales, in China or Japan. Captain Swallow favoured Tonga but the ‘China faction’ prevailed, leaving seven of the ‘Tonga faction’ on Niue Island but forcing Swallow to join them as navigator. As he later wrote, ‘They imprisoned me in the Cabin and kept me eight hours there when they ordered me to come upon Deck and Steer the Ship to Japan’.

The pirates probably had no knowledge of Japan’s self-imposed isolation and hostility towards foreigners. When Cyprus arrived off Yokohama with tattered sails and a crew desperate for water, they were met by a hail of musket and cannon shot. One passed so close to Swallow it knocked a telescope from his hands. A fortunate breeze sprang

up and the pirates fled for China. Swallow still entertained thoughts of the Pacific Islands but dissenting crew holed the vessel and paid a passing Chinese junk in pieces of eight to take them to land. Swallow and three remaining crewmen tried unsuccessfully to fother the vessel, then took to the longboat and presented themselves ashore as shipwreck survivors.

This cover story worked and they obtained passage as crew on a vessel returning to London. However their ruse came undone when their former shipmates turned up with the same story, but with contradictory facts. It must have been sorely disappointing, after such an epic journey, to be taken straight to prison when they landed in London. The magistrates had little evidence to go on, but by a strange quirk one of the ‘trusty’ convicts who had been marooned in Recherche Bay – and thereby earned his freedom – was in London at the time. So too was the Hobart Town gaoler, and the pirates were all recognised. Some were executed, others were sent back to Australia.