Louis de Rougemont died a long way from Australia, the place that made his name. He died a long way from Switzerland, the place in which he was born. In fact when he died, penniless and forgotten in London in June 1921, Louis de Rougemont was no longer his name at all. It was just a name that had once been famous.

It was also a name that came to be synonymous with a very strange and short-lived sport; turtle riding:

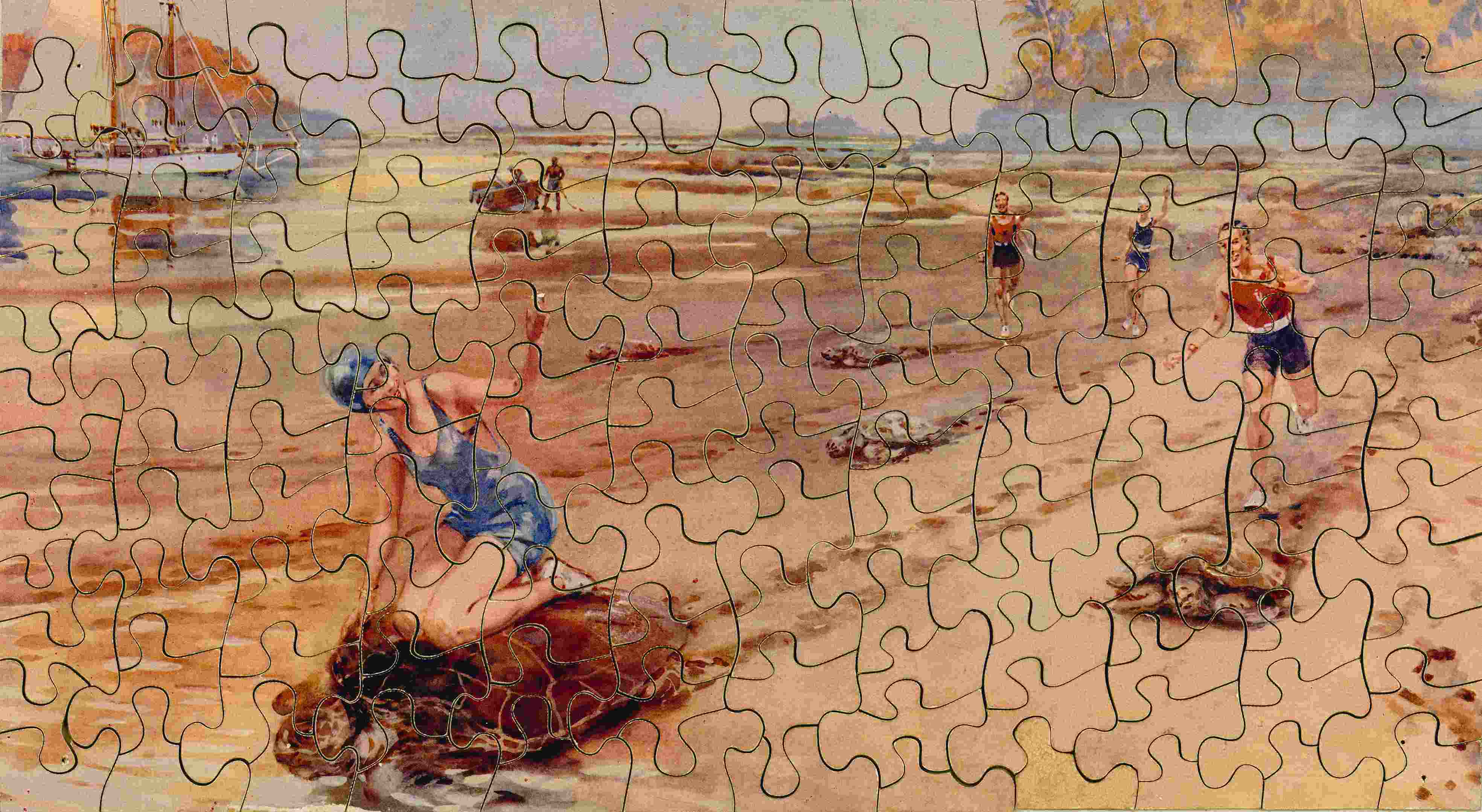

The unique sport of turtle riding in Australia was popular primarily throughout the 1920s and 30s where, during turtle nesting season, visitors to the Great Barrier Reef could observe the docile animals laying their eggs. Once on land and having laid their eggs, the turtles would be overturned, rendering them immobile for later sport. When the rider was ready a turtle could be turned upright, mounted and ridden into the sea with the most skilled riders being those who could control their steeds once in the water. Several turtle soup canneries operating in the area served as a base for these activities and their facilities, because of a lack of tourism infrastructure, were utilised by both holidaymakers and scientific expeditions alike. An early reference to turtle riding in Australia appeared in 1911 as part of a series of scientific lectures on the Great Barrier Reef by the Ornithologists Union of Australasia:

“an interesting diversification was found in riding out to sea on the backs of the turtle, a pastime which was found quite practicable as was shown in several lantern slides, the most interesting of which showed a young lady of the party in bathing costume besporting herself in the water astride one of the monsters, thus vindicating the astounding story of Louis de Rougemont.” (Evening News 1911)

De Rougemont’s story begins with his birth as Henri Louis Grin, in Switzerland in 1847. In 1875 Grin came to Australia where he bought the pearling cutter, Ada. The vessel was reported missing in 1877 and the wreck discovered several months later near Cooktown. But what had happened to Ada’s master? Grin’s story of survival was incredible: he made claims to have sailed 3000 miles as the sole survivor of an attack by Aborigines at Lacrosse Island.

After this incident Grin moved regularly, changing jobs and identities. He married and then deserted his wife, Eliza. He worked as a dishwasher, waiter and photographer. In New Zealand he resurfaced as a spiritualist before arriving in England in 1898. Emerging now as Louis de Rougemont, Grin reinvented himself and his story to a fascinated public. The Adventures of Louis de Rougemont as Told by Himself was published in 1899 and contained incredible tales of his adventures as a castaway in North-West and Central Australia.

De Rougemont’s book was an instant sensation – and caused a huge uproar. He began touring and giving lectures to scientific and exploration societies such as the British Association for the Advancement of Science where he was greeted with fascination and, of course, disbelief. De Rougemont refused to demonstrate the Aboriginal language skills he professed to have learnt and could not specify on a map where his adventures had taken place. Among the stories so vividly described in his book were tales of single-handedly fighting alligators, the devoted deeds of his Aboriginal wife Yamba and his horror of cannibal feasts. Of all of the fantastic stories included in de Rougemont’s ‘memoir’, however, the one that caused the biggest outcry by far was his claim to have ridden turtles – many believed this to be simply impossible. To counter this, in 1906 de Rougemont organised public demonstrations of turtle riding in England. One such display occurred in a large water tank at the London Hippodrome, you can read the outlandish account here.

The concurrent emergence of turtle riding as an activity in Australia proved that it was in fact possible, and this was often quoted as vindication for de Rougemont’s story (such as in the article above) however the lies came apart with the exposure, by his wife, of the would-be-adventurer as Henri Grin. De Rougemont continued to tour, now as ‘The Greatest Liar on Earth’, but by his death in 1921 he was working as a handyman under the name of Louis Redman.

As the controversy over de Rougemont’s adventures faded, turtle riding remained popular in Australia through to the 1920s and 30s where it was one of the few ways in which people observed and actively engaged with marine life. The odd pastime had all but disappeared, however, by the 1950s with changing attitudes in conservation and declining turtle numbers. Additionally, developments in scuba diving, snorkelling, glass-bottom boats and waterproof cameras all opened up other ways in which to expose marine creatures to eager eyes.

Did the sport of turtle riding vindicate any of de Rougemont’s astonishing claims? An English journalist perhaps answered this best when he wrote of ‘the Greatest Liar on Earth’:

Truth is stranger than fiction, but de Rougemont is stranger than both.

Penny Hyde

Curatorial assistant

![Turtle Riding in the Great Barrier Reef. ANMM Collection ANMS0850[143]](https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/anmm-data/blog/2013/08/10/turtle-riding.jpg)

Turtle Riding in the Great Barrier Reef. ANMM Collection ANMS0850[143]

‘Turtle riding into a blue lagoon – sport on the Great Barrier Reef’. Jigsaw puzzle, c1930s. ANMM Collection 00015492

![Tourists on a sandy beach in Queensland, two seated on sea turtles. ANMS0850[085]](https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/anmm-data/blog/2013/08/10/anms0850085.jpg)