Every small bit of sea has a name

– Djambawa Marawili

During National Reconciliation Week (27 May to 3 June), after extensive negotiations between Traditional Owners and the Federal and Northern Territory governments, it was announced that about 4000 square kilometres of ocean was added to the Dhimurru Indigenous Protected Area in North East Arnhem Land.

The Dhimurru Indigenous Protected Area was originally declared in November 2000. It covered an area of coastline and hinterland country on the western edge of the Gulf of Carpentaria – part of the traditional lands of the Yolŋu people. Importantly, a large area of sea country is now included.

While we are all aware of the long campaign for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land rights, the struggle for recognition of Indigenous peoples’ sea rights has had less public attention. Yet for traditional owners such as the Yolŋu people, land and sea are both inextricably ‘country’.

This was recognised as far back as 1973 by the Woodward Royal Commission into Land Rights. The commission led to the enactment of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act in 1976. It also recommended that the definition of Aboriginal land should include both off-shore islands and coastal waters.

Despite Aboriginal people asserting that their traditional rights extended well out to sea (as discussed at the 2012 Nawi conference about the sea-going abilities of Indigenous watercraft), the recognition of sea rights in the Act was watered down, and rights were only extended to the low water mark.

Ever since, there has been a struggle for the recognition of Indigenous sea rights. The Dhimurru Indigenous Protected Area marks another milestone in this struggle.

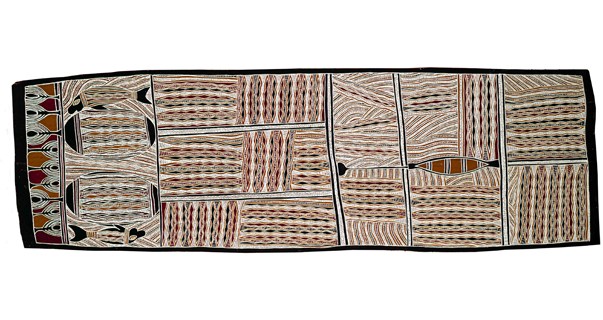

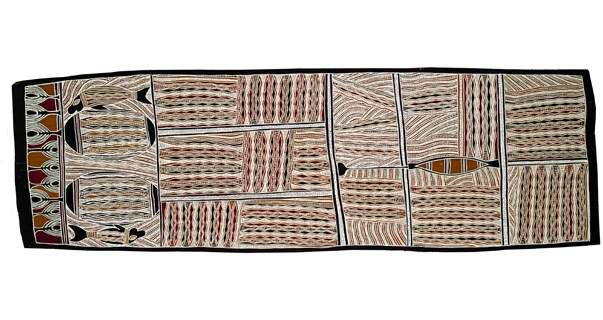

Yathikpa II artist Bakulanay Marawili 1998 ANMM Collection Purchased with the assistance of Stephen Grant of the GrantPirrie Gallery.

In this painting Bakulanay has shown the sacred saltwater of Yathikpa, where the Yolŋu people of north-east Arnhem Land first received fire from Bäru the Crocodile Ancestor.

A significant part of this has been about how to inform non-Indigenous people of the importance and role of the ocean in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

In 1996 in East Arnhem Land an illegal fishing camp was discovered hidden in the mangroves at Garraŋali, a sacred area in Blue Mud Bay. At the camp, a severed head of a crocodile was found. For Yolŋu people, this was a desecration of Bäru – the ancestor of the Madarrpa clan. Djambawa Marawili and 46 fellow Yolŋu artists began painting a series of barks that was designed to demonstrate to outsiders the rules, philosophies and stories of their region that related to the coast, rivers and waters.

This series of paintings was part a long line of political and legal battles where Yolŋu people have used their art, which spells out their law, to articulate their connection to the land and to the sea. When the Blue Mud Bay exclusive fishing rights case was being decided in the Federal High Court in 2008, senior Yolŋu artists knew that the evidence of their title to saltwater country did not have to be presented to the court in written documents on paper – it already existed in Yolŋu art.

The paintings describing Yolŋu sea country are now called the Saltwater Collection and form an important part of the National Maritime Museum’s collection. A selection of the barks – including those presented as evidence in the Blue Mud Bay case – currently form the centrepiece of a display at the museum called Saltwater Visions.

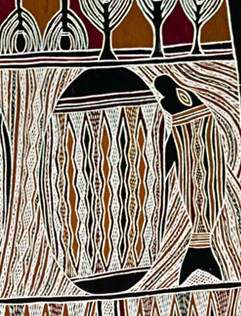

Detail from Yathikpa II artist Bakulanay Marawili 1998 ANMM Collection. Purchased with the assistance of Stephen Grant of the GrantPirrie Gallery. Here we see a dugong and the sacred rock Marrtjala.

The Saltwater Collection barks are part of a broader tradition of Indigenous art as a point of understanding for non-Indigenous people. In 1963, Yolŋu people from Yirrkala in northeast Arnhem Land sent two bark petitions to Federal Parliament. The petitions protested the government’s granting of mining rights on land that had been previously reserved for Aboriginal people, and sought the recognition by the Australian Parliament of the Yolŋu peoples’ traditional rights and ownership of their lands.

The bark petitions helped shape a national acknowledgment of the rights of Aboriginal people and were a catalyst for the 1967 referendum and ultimately, the overturning of the concept of terra nullius in the Mabo High Court Case of 1992.

NAIDOC Week is the annual celebration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and achievements. The focus for NAIDOC Week in 2013 is on remembering the vision, fifty years ago, of the artists of the famous Yirrkala Bark Petitions.

National Reconciliation Week is 27 May to 3 June 2013

NAIDOC Week 2013 – We value the vision: Yirrkala Bark Petitions 1963 is 7 to 14 July

Saltwater Visions is on display 23 May to 6 October