On Valentine’s Day in 1779 Captain James Cook was killed in the Hawaiian Islands. Ironically perhaps, his death was the beginning of a long love affair with Cook by generations of people in the Western world who revered the great navigator. It was also the beginning of 56 long years for his wife Elizabeth Cook, without the love of her life.

When news of Cook’s death reached Britain the nation was deeply shocked. We can only imagine what his wife Elizabeth felt at the death of her husband of 17 years. Was the fact he died on Valentine’s Day a recurring wound for her?

Comparatively little is known of Elizabeth. She was born in 1741, the only child of Samuel and Mary Batts, who ran the Bell Alehouse at Execution Dock in Wapping. She was from a family of curriers (leatherworkers) and while not poor, like many women from the lower middle classes of the time, a naval officer with career prospects would have been a reasonable catch. In 1762 she married James Cook at St Margaret’s Church, Barking in 1762. Elizabeth was 21 and James 34 years old. As the eminent biographer of Cook J C Beaglehole put it, ‘it was a respectable rather than socially distinguished union.’

James’ cartographic and navigational skills saw his services in the Royal Navy in increasing demand. This of course meant many long periods at sea. Of their 17 years of marriage, James spent a total of only four years living with his wife.

While James’ career went from strength to strength, Elizabeth’s story is tinged with sadness. When James was away on his ill-fated third voyage, Elizabeth had been busy embroidering a new waistcoat for him made from Tahitian tapa cloth he had brought back from his second voyage. She, and no doubt others, expected him on his return to be required to attend the Royal Court. The waistcoat remained unfinished.

Cook died at the age of 50, but Elizabeth reached the age of 94, surviving the death of her husband by some 56 years. She also outlived all of her six children. Three of them died in infancy, one from scarlet fever in his teens and two while serving in the Royal Navy. Nor were there any grandchildren to comfort her.

Elizabeth never remarried. She dressed in mourning black well after the accepted period of the time. Like many navy widows of the time, she cherished mementos of her husband. She carefully preserved items from her husband’s uniform, including his dress sword and shoe buckles. She continued to wear a cameo-style memorial ring and was wearing this in a portrait painted of her aged in her eighties.

She also kept a small, coffin-shaped, wooden ‘ditty box’ which held a tiny painting of Cook’s death and a lock of his hair. This little relic was carved by sailors on Cook’s last ship, HMS Resolution, as a keepsake for Mrs Cook.

While she lived in financial comfort with a pension provided by King George III and income received from the sale of books detailing Cook’s voyages, hers would have been a lonely family life until she died on 13 May 1835. Many of Elizabeth’s mementos of James were kept by her relatives and are now held in the State Library of NSW collection.

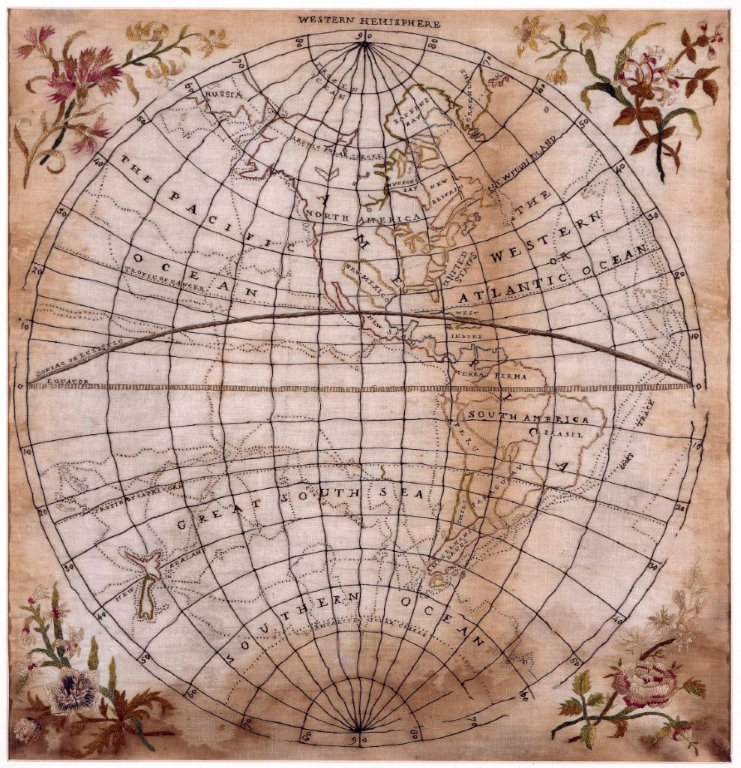

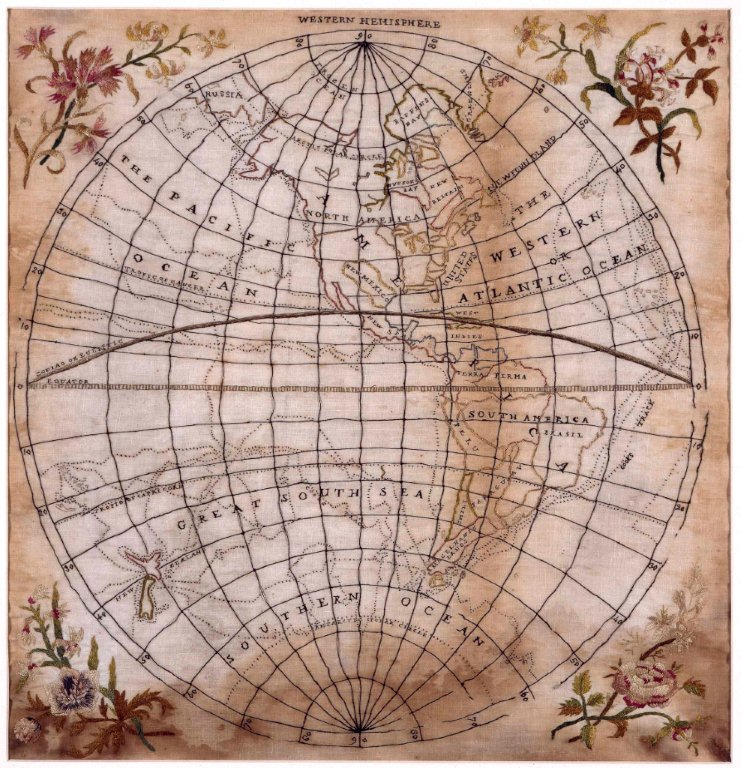

This embroidered map in the Australian National Maritime Museum collection is attributed to Elizabeth Cook. It depicts her husband’s three voyages to the Pacific and is decorated with floral sprigs. This intriguing mixture of navigational science and domestic arts seems to suture the schism between a love of service to empire and a love between two people.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of the love between Elizabeth and James was that in later life she burned all the letters she had received from him. Considering his time spent at sea, there must have been many. As time passed after James’s death Elizabeth would have known that with the great reverence of James around the world there would be strong public interest in the contents of their letters.

Should we call them love letters? Although occasionally prone to outbursts of ‘cold rage’ (usually directed at ‘troublesome Natives’ rather than his crew) Cook was generally circumspect and not prone to outbursts of emotion. Were there love letters among them? We shall never know. But the effect of this incineration was that any opportunity for historians to know more about ‘the man’ James Cook and the dutiful yet perhaps forlorn Elizabeth, were lost to years of hagiographical historiography attempting to flesh out the character of the great navigator James Cook.