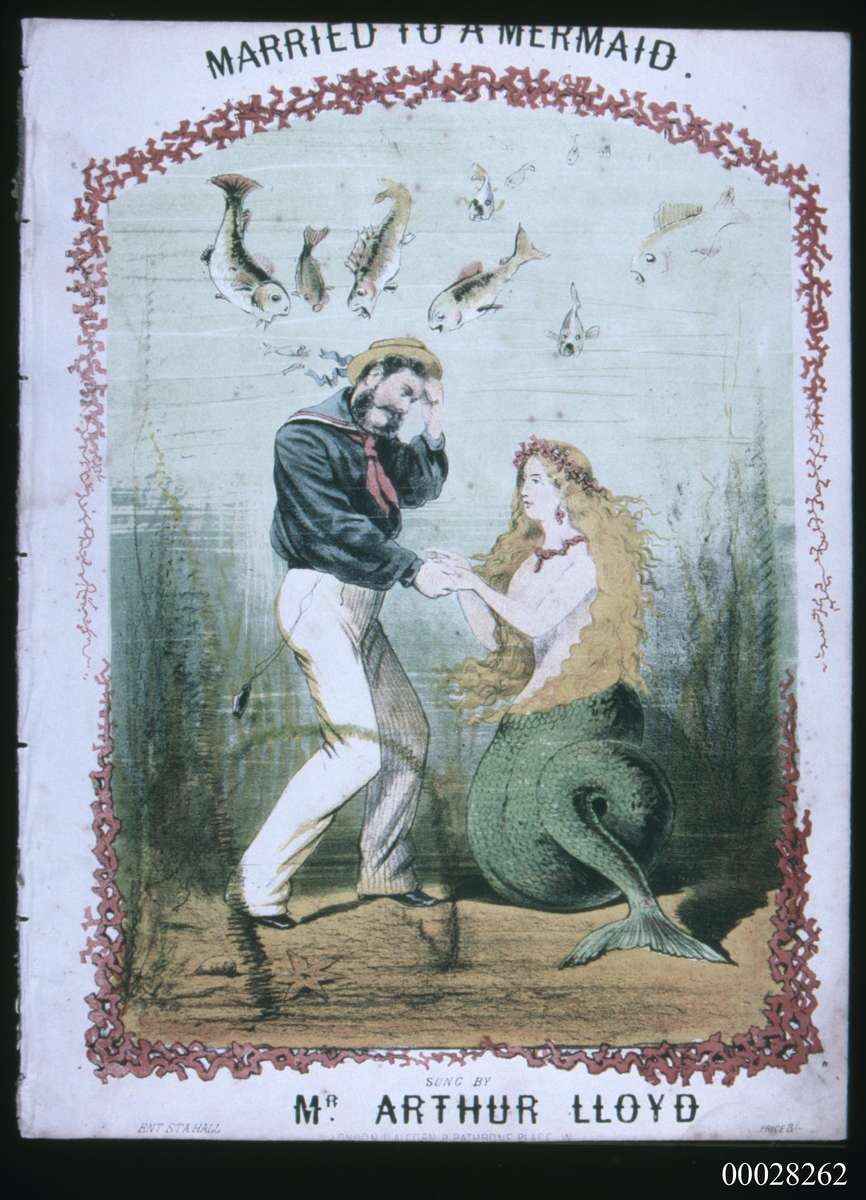

Married to a Mermaid, about 1866

I was trawling through the museum’s collection of sheet music when Married to a Mermaid (about 1866) caught my eye. Initially, I was struck by the peculiarity of the image; a sailor is depicted holding hands with a mermaid on the seabed with what appears to be animated fish hovering above. A closer look at this item and other examples in the collection, however, reveals that these lyrical verses and colourful images also communicate cautionary tales and heroic deeds. Musical stories struck a chord with 18th and 19th century listeners, and added to commonly held romantic notions surrounding life at sea.

The publication of music reached its peak in the 19th century as recital halls, theatre shows and parlour music became an integral part of social life in Britain, Australia and America. Sheet music publishers flourished and their product was sold cheaply and widely distributed. In this sense, sheet music represented an easily accessible form of entertainment and social interaction.

Considering the cultural and social significance of sheet music, Married to a Mermaid ventures beyond a tale of unlikely romance. Contained within its pages appear the lyrics to the British patriotic song, Rule Britannia! Sung by Arthur Lloyd, a famous music hall performer and comedian, audiences would have instantly recognised this song. This particular version of it gained popularity in 1755 when it featured in Masque of Britannia, at a theatre in Drury Lane, London.

Amidst this patriotic fervour and the unusual marriage situation, however, exists a much gloomier reality, and one that would have resonated with seafarers. The song seems to disguise the fact that the sailor essentially fell overboard to his watery grave. It acts as a light-hearted but evocative tale of what was considered a real threat to those at sea. The upbeat nature of the song was designed to lessen the fear associated with this dark reality, as he is described as being finally ‘free’ in the ‘deep blue sea’. This concept, combined with that pivotal sense of sailor camaraderie, is especially evident in the following lyrics, spoken from the sailor’s point of view:

‘My comrades and my messmates,

Oh, do not weep for me,

For I’m married to a mermaid,

At the bottom of the deep blue sea.’

Another rather colourful tale of woe can be seen in The sailor’s complaint (about 1735), in which a woman is depicted holding a basket and greeting a sailor disembarking from a naval frigate. Like Married to a Mermaid, it functions as a cautionary but light-hearted story. A sailor, ‘who was once so stout and bold’ is jilted by ‘scornful Sue’. The song is littered with nautical metaphors, perhaps intended to connect with its seafaring listeners. The sailor describes how he was ‘cast away’ by this ‘Goddess bright’ and ‘could not compass her’ ‘to steer the marriage course.’

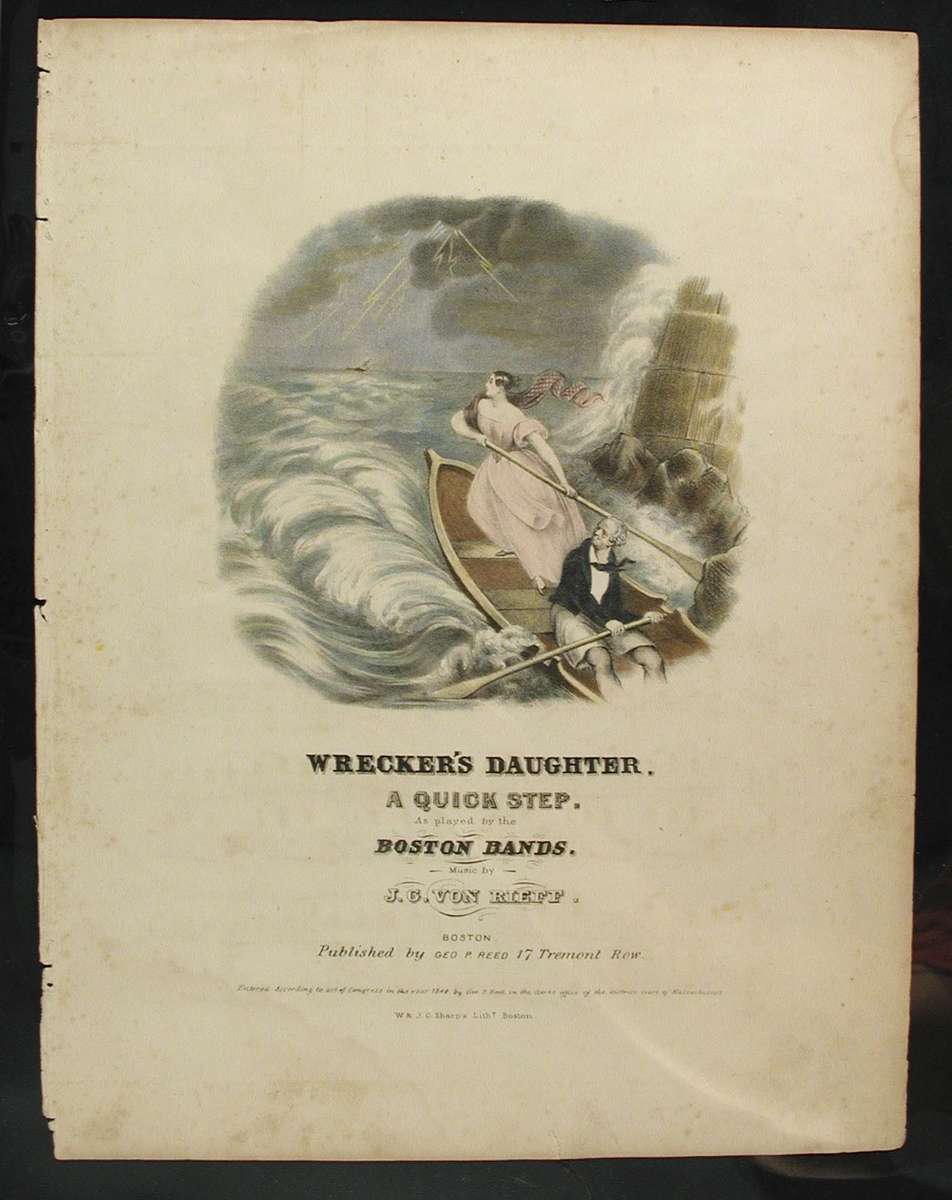

Wrecker's Daughter, 1840

Amusing metaphors and unrequited love aside, another piece in the collection demonstrates how sheet music provided a popular cultural outlet for maritime experiences and events. Wreckers Daughter (1840), a quick step dance, recounts the story of Grace Horsley Darling. At just 23 years of age, she rescued nine people from the wreck of SS Forfarshire, which sank near the Farne Islands off the coast of Northumberland in 1838. Within days of the tragedy, Grace’s story of survival during what was considered a suicidal mission spread to neighbouring towns and eventually across the Atlantic to America, which is where this item originated. Accounts of Grace and her actions exhibit a romanticised view of the rough-and-ready nature of seaside dwellers. In 1841, Charles Ellms detailed her ‘noble heroism’ despite her solitary existence in Longstone lighthouse, a ‘lonely spot in the middle of the ocean’. Grace died of tuberculosis in 1842, four years after the sinking of SS Forfarshire. In light of the numerous cultural tributes to Grace following her death, Ellms’ earlier predictions seem particularly poignant:

‘Eminent poets, dramatists, and painters, have vied with each other in extending her renown. And the name of Grace Darling is destined to live in story, long after the ponderous blocks of granite, which compose the Longstone lighthouse, have crumbled from their foundation, and been ground into sand by the attrition of the surrounding ocean.’

At the heart of each piece, sheet music displays prevalent social and cultural motifs. With each stanza, life’s questions are parodied or sentimentalised in a compelling way. These tales form part of a range of maritime themed songs; a vibrant collection of narratives designed to illustrate messages of love, friendships, identity and heroism.

See a ballad from the collection, regarding Grace’s noble actions here.

For other examples of sheet music in the museum’s collection click here.

Nicole Cama

Curatorial assistant