Broadsheet newsprint telling the tale of the shipwreck of the transport FLORA

This broadsheet newsprint tells the tragic tale of a convict’s wife who was sent to the Bedlam asylum in London after murdering a crew member of the shipwrecked vessel Flora. The ship was wrecked in 1832 en route from Australia, however the truth at the heart of this tale of murder and madness is a little harder to find…

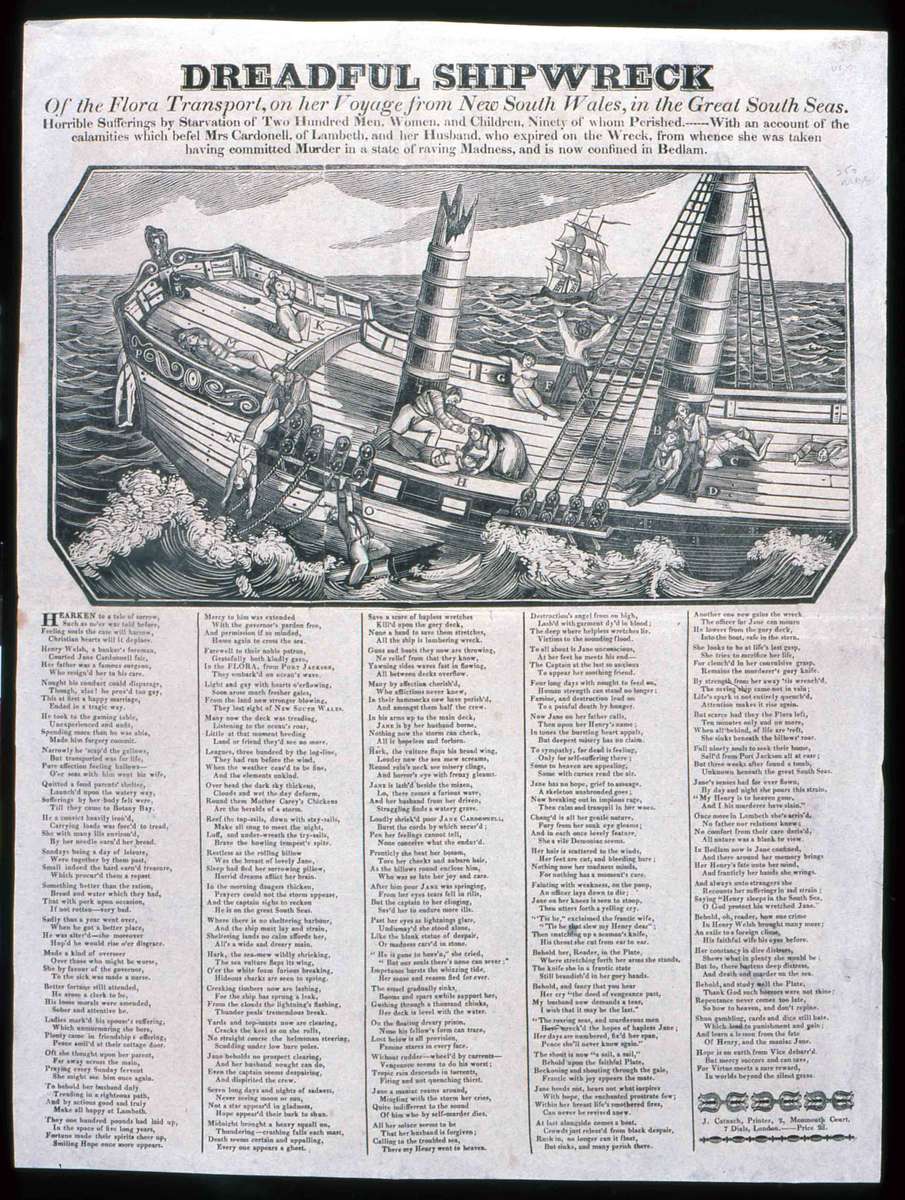

This item is a rare record of the sinking of Flora, one of many ships to fall victim to the reefs of north-east Queensland, but in itself a little known event. The poem and its accompanying image of despairing survivors and a woman slashing the throat of a man on the deck of a wrecked ship, paints a horrific scene. The narrative revolves around the tale of Jane Cardonell, her romance with Henry Welsh, and their fateful passage on Flora.

It begins with the courtship of Henry, a banker’s foreman, and Jane, a surgeon’s daughter whose happy marriage preceded Henry’s descent into gambling and forgery:

Narrowly he ‘scap’d the gallows,

But transported was for life,

Pure affection feeling hallows-

O’er seas with him went his wife.

The story goes on to tell of Henry and Jane’s misfortune as they are transported from England to Botany Bay, he in chains and she as a convict’s wife. However the couple work hard during their time in the colony and a sober Henry and his devoted wife soon improve their position. Within five years Henry is granted a pardon, their passage home to England is assured and they embark on the Flora from Sydney to return to Jane’s family. However soon after leaving Port Jackson the ship is struck by terrible weather and many ominous signs surround the vessel and its hapless passengers:

Hark, the sea-mew wildly shrieking,

The sea vulture flaps its wing,

O’er the white foam furious breaking,

Hideous sharks are seen to spring.

As the ship begins to break apart and lose its battle with the elements, Jane begins to lose her sanity:

Restless as the rolling billow,

Was the breast of lovely Jane,

Sleep had fled her sorrowing pillow,

Horrid dreams afflict her brain.

After seven days at sea on the wrecked ship, Jane is carried to the main deck in the arms of her husband when a furious wave sweeps over the ship and takes Henry to his death. As the ship continues to sink and her husband is enveloped by the sea, Jane attempts to jump in after him but is stopped in her rush by the captain, who saves her to ‘endure more ills’. In the days that follow, the survivors are lead to death by famine, storms and maddening thirst. Jane finds solace only in the fact that her husband had been pardoned, and has found his way to heaven – however she is becoming increasingly mad with grief.

Chang’d is all her gentle nature,

Fury from her sunk eye gleams,

And in each once lovely feature,

She is a vile Demoniac seems.

As her madness reaches its peak, Jane leaps upon a dying crew member and snatching up a seaman’s knife she declares ‘Tis he that slew my Henry!’ – slashing his throat from ear to ear. Before she can take her own life too, a boat comes alongside to rescue the survivors and Jane, with the still-bloodied knife in her hands, is taken on board. As the lifeboat steers away from the wreck of the Flora, the ship succumbs to the sea and sinks beneath the waves, taking with it 90 lives. The tragic tale ends with Jane’s arrival in England, and her internment in the Bedlam asylum. The final lines address the reader directly to learn from the fate of Henry and the maniac Jane – warning of the ills of crime, and advising repentance:

Behold, and study well the Plate,

Thank God such horrors were not thine:

Repentance never comes too late,

So bow to heaven, and don’t repine.

The story told by this broadsheet verse is tragic, graphic and moralising and would have been intended for a wide audience. These types of prints were a cheap and popular form of entertainment that tended to take inspiration for their tales from contemporary events or stories. There are not many sources available for the sinking of the Flora, making this broadsheet an interesting and valuable item, however there are, of course, issues with the story’s authenticity.

The Sydney Herald and The Sydney Gazette both printed stories about Flora’s fate after it left Sydney in April 1832, bound for Batavia (Jakarta). The stories in these publications record that Flora was wrecked on the Barrier Reef on 1 May 1832 stating:

The first trial of the crew and passenger, for there was only one, an elderly European female, was to pass the night in this situation with the momentary prospect of the vessel going to pieces.

According to the newspaper reports, the next day the vessel was discovered to be completely wrecked and the group took the longboat – the only one not to be irretrievably damaged – and a small amount of rations before abandoning Flora. The reports state that there were a total of 37 survivors and no loss of life during the incident. After spending two nights on an island, the exhausted company arrived at Dili, Timor, where twenty members of the crew stayed. The remainder sailed onto Kupang and here many of the crew moved on to other ships, while Captain Sheriff and the female passenger were taken to Madras by the Norfolk. The newspaper articles both appear in early 1833, the year after the fateful voyage, and both credit sources in Madras for the story.

Whether the elderly female passenger bears any other resemblance to Jane Cardonell other than her sex remains to be seen. There is no mention of madness or youthful marriage for this passenger and she fails to slash any throats whatsoever during her ordeal. Similarly, the 90 watery graves of the poem are absent from the contemporary reports, rather all on board survived to reach land.

Most broadsheets don’t have a date, however we can perhaps assume that this item was printed soon after the sinking of Flora, an event that may well have been fresh in the mind of the public. The writer perhaps allowed some license in the storytelling to capitalise on the public’s interest in tales of shipwrecks and atrocity – during a time when most people would have experienced travel by sea themselves and felt the threat of a shipwrecked fate.

PH