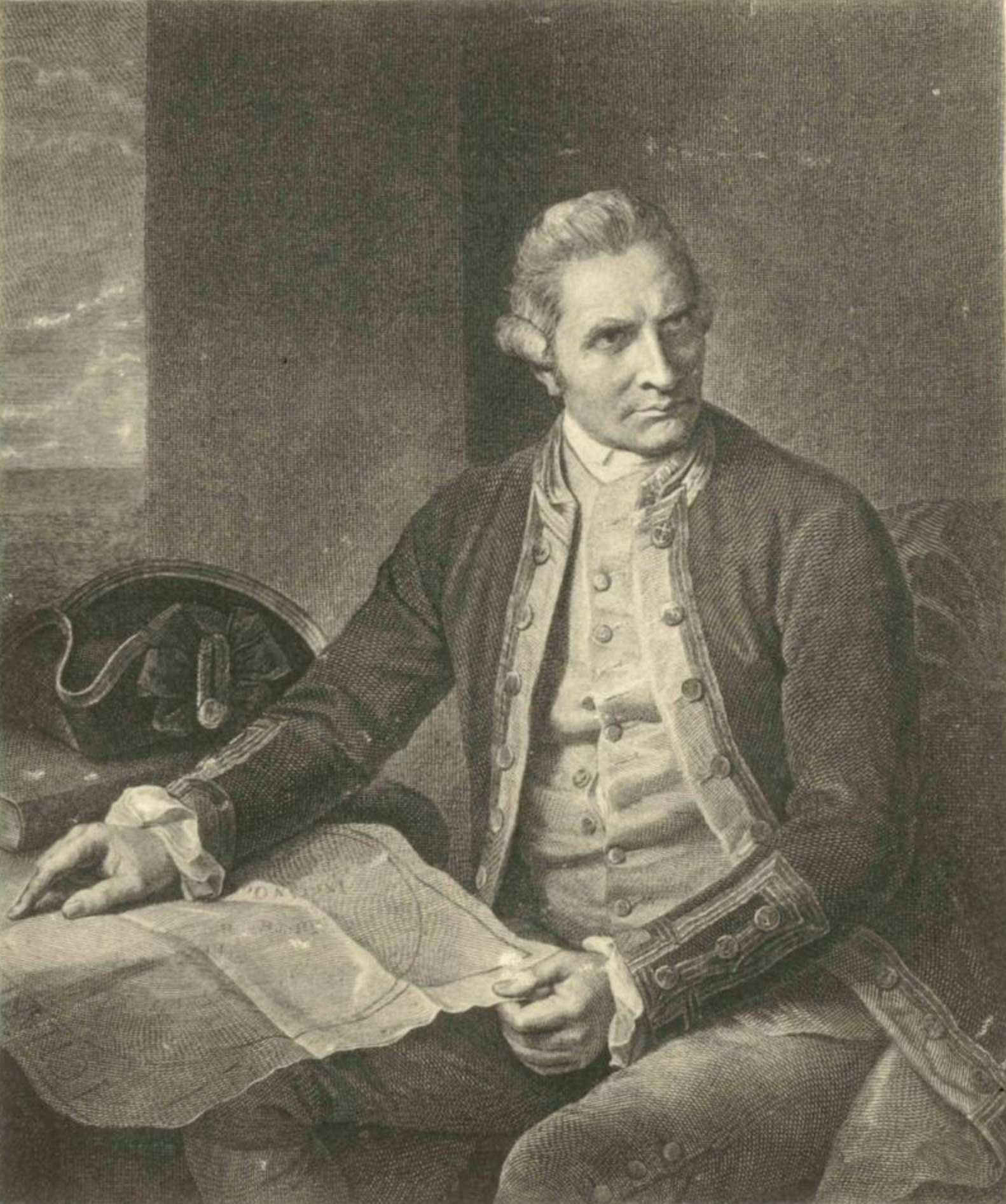

In the late 1700s, the small seaside village of Whitby was known as a 'nursery' for mariners, where expert shipbuilders and the most competent seafarers completed their apprenticeships. This centre for commercial trade bred colliers—sturdy ships capable of carrying heavy loads, including coal, across the Baltic Sea and beyond. They were steady workhorses that could be relied upon. Their solid, flat-floored hulls were adept in navigating shallow harbours and estuaries. Earl of Pembroke was one such vessel, built by Thomas Fishburn for Thomas Milner in 1764. One of its rare and distinguishing features was a 'deadwood' or 'rider' keelson that ran along the inside bottom of the hull. This reinforcing centreline timber prevented the vessel from breaking its back when loading or unloading cargo in shallow tidal waters. The son of a Yorkshire farmer learned how to sail on ships such as these. His name was James Cook.

A typical collier moored in Whitby Harbor, identified as Earl of Pembroke by painter Thomas Luny. Image credit: The National Library of Australia.

Letter dated 27 March 1768

From: The Yard Officers, Deptford

To: The Royal Navy Board

“We have surveyed and measured the undermentioned ships recommended to your Honours to proceed on Foreign Service and send you an account of their quantities, condition, age and dimensions … The Earl of Pembroke, Mr Thos. Milner, ownes [sic] was built at Whitby, her age three years nine months, square stern bark, single bottom, full built and comes nearest to the tonnage mentioned in your warrant and not so old by fourteen months, is a promising ship for sailing of this kind and fit to stow provisions and stores as may be put on board her.”

Letter dated 29 March 1768

From: The Royal Navy Board

To: The Secretary of the Admiralty

“We desire that you will inform their Lordships that we have purchased a catbuilt bark, in burthen 368 tons, and of the age of three years and nine months, for conveying such persons as shall be thought proper to the southward for making observations of the passage of the planet Venus over the disc of the sun, and pray to be favoured with their Lordships’ directions for fitting her for this service accordingly … and that we may also receive Their commands by what name she shall be registered on the list of the Navy.”

Letter dated 5 April 1768

From: The Lords of the Admiralty

To: The Royal Navy Board

“We do hereby desire and direct you to cause the said vessel to be sheathed, filled, and fitted in all respects proper for that service, and to report to us when she will be ready to receive men. And you are to cause the said vessel to be registered on the list of the Royal Navy as a bark by the name of the Endeavour”

And with that, the humble Earl of Pembroke became H.M Bark Endeavour, now employed in the service of George III, King of Great Britain, and King of Ireland. Once fitted with a large provision of goods to see out a three-year voyage in uncharted waters, the lives of nearly a hundred men aboard depended on this ‘bark’ and the skills of her commander, Lieutenant James Cook, in navigating the unknown.

The Endeavour voyage was, on the surface, a scientific mission. Lieutenant Cook’s first orders were to set sail for Tahiti, a tiny island in the South Pacific that he skilfully steered a course to by the moon and the stars. The crew arrived right on time to observe the Transit of Venus—a once in a lifetime celestial event that would allow astronomers to calculate the distance from the earth to the sun and the size of the solar system for the first time. It was there that Cook opened a sealed packet, containing secret orders to find Terra Australis Incognita, or the ‘unknown southern land' that was thought to exist but yet to be confirmed.

"You are therefore in Pursuance of His Majesty’s Pleasure hereby requir’d [sic] and directed to put to Sea with the Bark you Command so soon as the Observation of the Transit of the Planet Venus shall be finished and observe the following instructions.

You are to proceed to the Southward in order to make discovery of the Continent above-mentioned until you arrive in the latitude of 40° unless you sooner fall in with it."

It was this latter mission that led to Cook’s mapping of the eastern coast of Australia, a land long occupied by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with their own distinct languages, cultures, and knowledge—passed on through songlines embedded in Country and waters. But Cook had his instructions from the Admiralty, which referred to Australia’s Indigenous peoples in the language of the day:

You are [...] to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the

Natives, if there be any, and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate Friendship and Alliance with them…

You are also with the Consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain. Or, if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors.

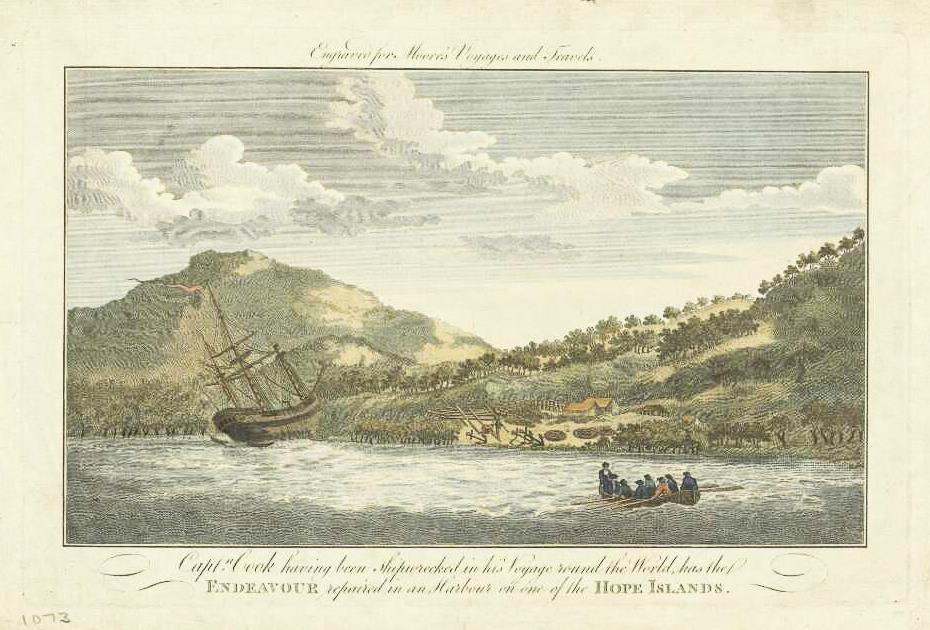

Consent to enter Aboriginal lands or to claim possession was never given. As they travelled along the east coast, Cook and his men saw evidence of the peoples of many Aboriginal nations. His journals noted many sightings of smoke and signal fires. While transiting north off the present-day coast of Queensland, Endeavour struck upon the Great Barrier Reef. There is no way Cook could have known the extent of this vast network of coral reefs and shallow shoals and it nearly spelled the end of the voyage. The crew strived frantically for a day and a night to avoid sinking while the ship took on water. Among the first items thrown overboard were heavy cannons, followed by iron ballast and nonessential provisions. The arduous work paid off. Cook and his crew spent several weeks living on the lands of the Guugu Yimithirr people while the damage to Endeavour was assessed. The Whitby collier was built strong enough to withstand such unpredictable occurrences and conditions. But perhaps if Endeavour were another type of vessel, the fate of Cook and his crew, and the history of Australia, would be much different.

Endeavour being repaired after striking the Great Barrier Reef. Image credit: Australian National Maritime Museum.

With the hardy Endeavour temporarily patched up, it was repaired in Batavia (modern day Jakarta), Indonesia, before sailing back to England––victorious. Cook went on to lead two more world-spanning voyages in newly fitted-out ships, like HMS Resolution. But Endeavour was redirected, ferrying troops and military supplies to British Army regiments stationed in the Falkland Islands. By 7 March 1775, the worn-out bark was sold for a sum of £645 and returned to the routine trade routes of a merchant collier operating in the North Sea. As to its fate? For many years, the popular consensus was that Endeavour had been purchased by French merchants for use as a whaling vessel and given yet another name—La Liberté.

“She arrived in Newport and lay alongside one of the wharves for some months, and then, having at last received a cargo, she ran aground in trying to leave the harbour, and proving on survey to be in a very bad condition, she was allowed to remain where she was and drop to pieces."

It was far from a dignified ending, but there the story settled. The timbers that could be salvaged were used to build a new whaler—Wareham. Artefacts such as the carved crown were taken from the stern for souvenirs, and pieces of the vessel remain in the hands of collectors around the world today. A parking lot was built on reclaimed land, where the wreck was likely located, and that seemed to close the chapter on this extraordinary ship’s history.

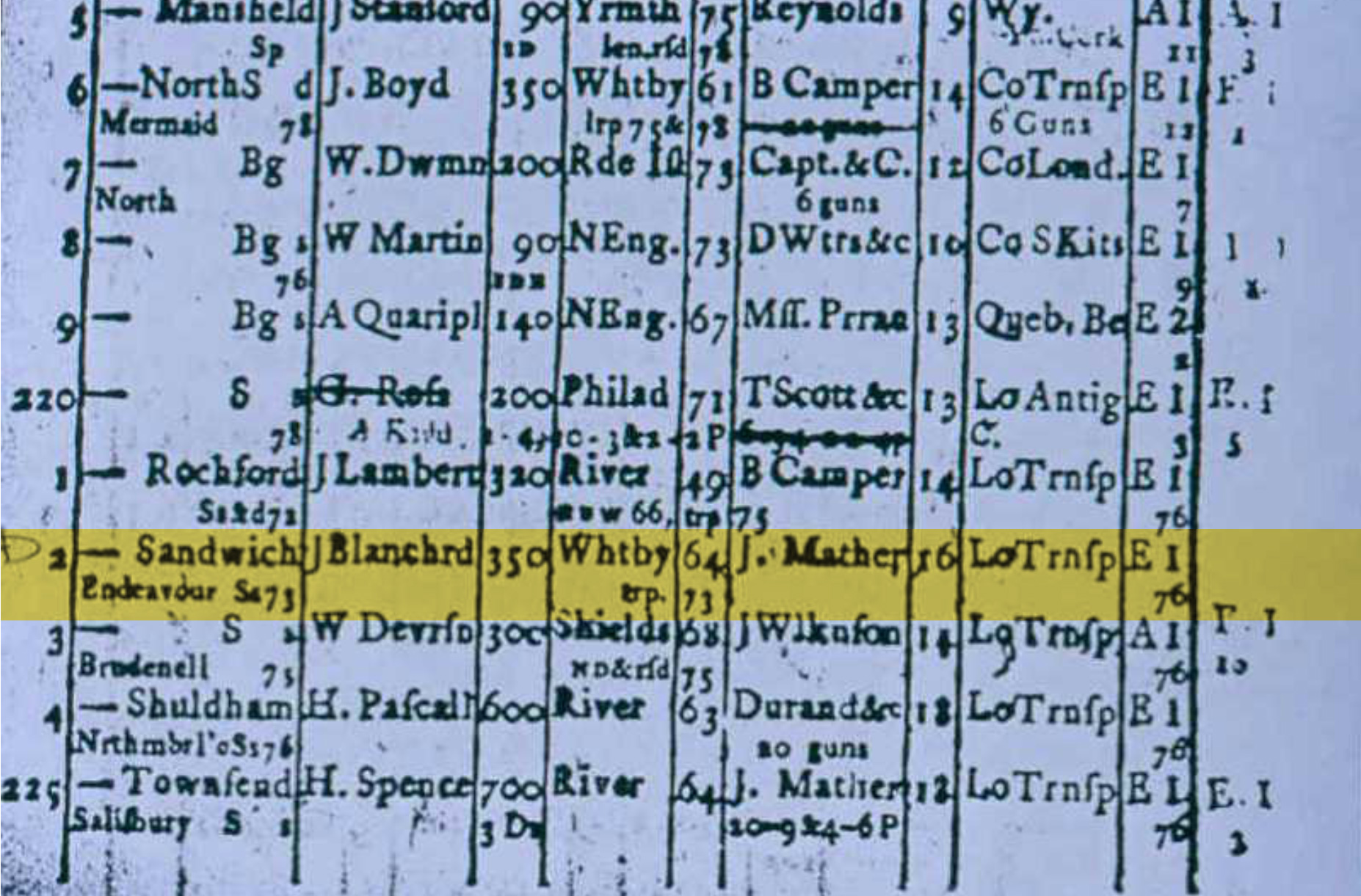

That is, until 1997, when two Australian historians, Mike Connell and Des Liddy, uncovered clues in the 1776 edition of Lloyds Register of Shipping that Endeavour was, in fact, renamed Lord Sandwich and that La Liberté was Cook’s other ship, Resolution. Hot on the trail was Dr Kathy Abbass from RIMAP, who recalls:

When the Connell-Liddy article arrived at the RIMAP office in early 1998, it did not take much imagination to speculate that the Lord Sandwich transport, used as a prison ship and possibly sunk in Newport in 1778, was the same vessel. This meant that the local lore about the loss of Endeavour in Newport was correct, but that the story had confused two vessels lost fifteen years apart and in different parts of the harbour.

During a visit to the United Kingdom, Dr Abbass found evidence at the Public Records Office in Kew that the Lord Sandwich sunk in Newport Harbor in 1778 was formerly HMB Endeavour.

An extract from Lloyd's Register of Shipping, 1777, showing HMB Endeavour renamed as Lord Sandwich.

Deptford Yard Copy Book

23 December 1775

Lord Sandwich 2d: unfit for Service She was Sold out of service Called Endeavour Bark refused before.

February 4, 1776

In Obedience to your directions of the 21st past, we have Surveyed and examined the Bottom of the Ship undermentioned, and find her fit for the Transport Service, and she having been formerly measured, we send you an Account thereof ... built at Whitby, and rep[aire]d lately in the River, Bottom Sheathed, has riser to her Quarter Deck and Forecastle, is roomly and has good accommodations, her Lower Deck laid.

The report gives measurements that exactly match those of Earl of Pembroke when it was first surveyed in detail by the Royal Navy. With a bit of refurbishment, Lord Sandwich was deemed fit enough to support the war effort.

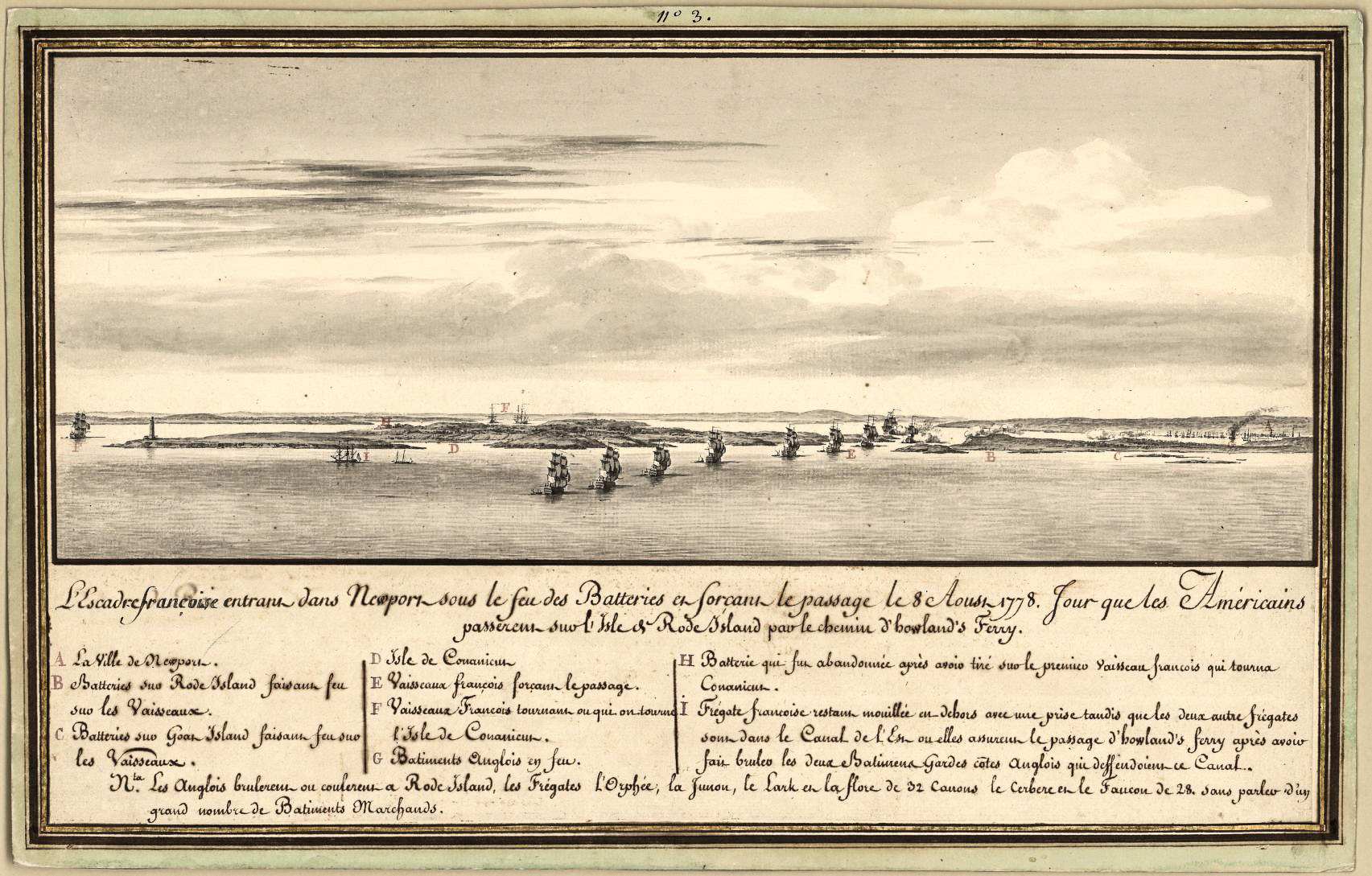

Lord Sandwich aided the British in the American War of Independence by transporting German mercenary troops from Europe to North America, and for a time served as a prison ship in Newport Harbor, holding American patriots captured during the conflict. Once the British learned a superior fleet sent by the French (who had recently joined the conflict on the side of the Americans) was approaching Rhode Island, they blocked access to Newport by intentionally sinking ships on the north, south and west sides of Goat Island. Among them was Lord Sandwich. A technique, known as ‘scuttling’, was used to carefully sink a ship so that it wouldn’t capsize, but rather land on the seabed upright, with its masts still standing vertically in order to block the passage of enemy ships. One of the museum's maritime archaeologists, Dr James Hunter, describes the complicated process:

“I just imagine some poor soul having to go down there in the hold of the ship. It would be pitch-black, he’d be given a hammer and a chisel and be told, ‘go and knock a couple of holes in this vessel, and by the way, you’d better run really quick because the water's going to flood in’. I can just imagine it. Three, three and a half inches, about a hundred millimetres of planking, they had to chop through quickly, not an easy task. And it would have been a group of them doing it. They would have been yelling back and forth – ‘how far are you in?’ And you have to remember in the hold of the ship, there's only one or two ways out and they have to scramble over the ballast, negotiate the timbers of the ship. I just imagine trying to get out on the ladder—four or five guys, all scrambling as the water was coming in, and doing everything by candle or lamp light.”

Ships were scuttled this way with the intention of later recovering them for reuse; however, after the French retreated the British decided to leave many of the scuttled ships behind, including Lord Sandwich, as it was considered no longer fit for service, or worth the effort to re-float.

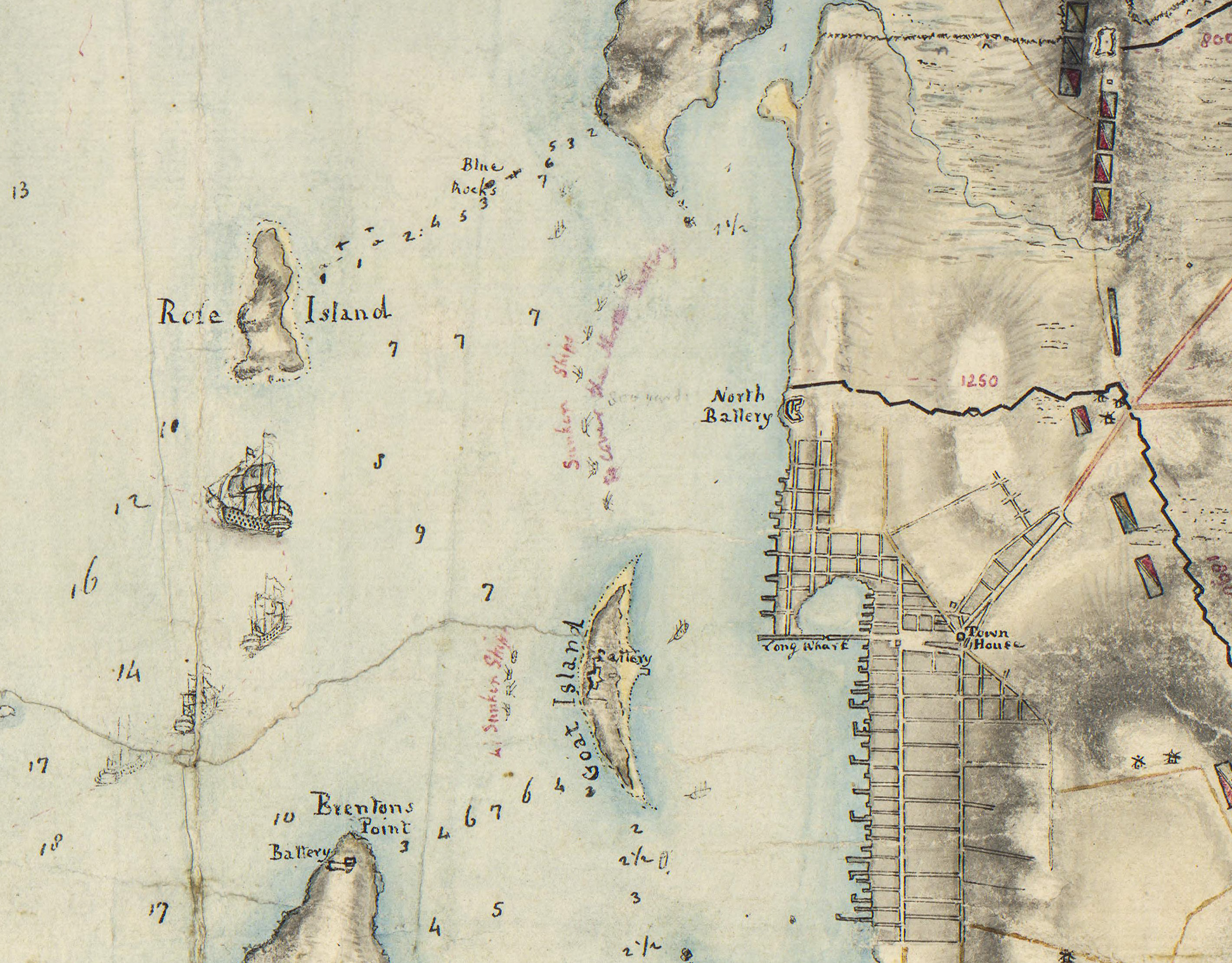

This chart of Newport Harbor is inscribed with notes in red ink that indicate the location of scuttled transports surrounding Goat Island. Image credit: William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

The Earl of Pembroke launched in Whitby, England

Plied the northern trade routes as a collier

Documented, purchased and refitted by the Royal Navy

Renamed the HMB Endeavour

Lieutenant James Cook's first Pacific voyage to witness the Transit of Venus

The first European vessel to document the eastern coast of Australia

A return to navy transport ferrying soldiers and goods to the Falkland Islands

The worn-out Endeavour was sold by the Royal Navy

The refurbished Endeavour was once again purchased by the Royal Navy

Renamed Lord Sandwich in preparation for The American Revolutionary War

Carried British and Hessian soldiers into battle

Used as a prison ship to confine captured American patriots in Newport

Scuttled and sunk as a defensive block ship in Newport Harbour, Rhode Island

Considering The Evidence

2021 (Sydney, Australia)

I love the ability to be able to touch the past, to be the first person, to see something that has been buried for 100, 200, 2,000, 3,000 years. By looking at the way the objects interrelate to each other, I can learn a lot more about how people lived in the past.

— Keiran Hosty