The COVID-19 crisis reminded Australians of both the effectiveness and the frailties of quarantine. Sometimes the system slips up, as our Head of Knowledge Dr Peter Hobbins reveals in a historical precedent to the Ruby Princess episode of 2020.

Picture this. A huge ship sails into Sydney Harbour with potential cases of a highly infectious disease aboard. Despite official precautions, the passengers are not quarantined and patients incubating the illness disembark. Many journey on to their home states, mingling with the local community until tell-tale symptoms emerge. Amid frantic attempts to trace the travellers across the country, Australia’s quarantine credentials are challenged and the public demands an explanation.

The story certainly sounds familiar to anyone who followed the Ruby Princess fiasco of March 2020. A Special Commission of Inquiry concluded that health officials responsible for managing the cruise ship’s arrival ‘were diligent, and properly organised’, but ‘despite the best efforts of all, some serious mistakes were made’.1

The same assertions were certainly true for a strikingly similar incident in 1929. Embroiling the Union Steam Ship Company’s RMMS Aorangi, it involved medical misdiagnosis, slipshod paperwork, conflicting jurisdictions and a clash of powerful personalities. Although no lives were lost, one unwitting celebrity was condemned to lifelong quarantine far from home. Luckily, this victim was an Arizona-born donkey named ‘Hot Beans’, and he didn’t seem to mind spending the remainder of his life in Perth Zoo.

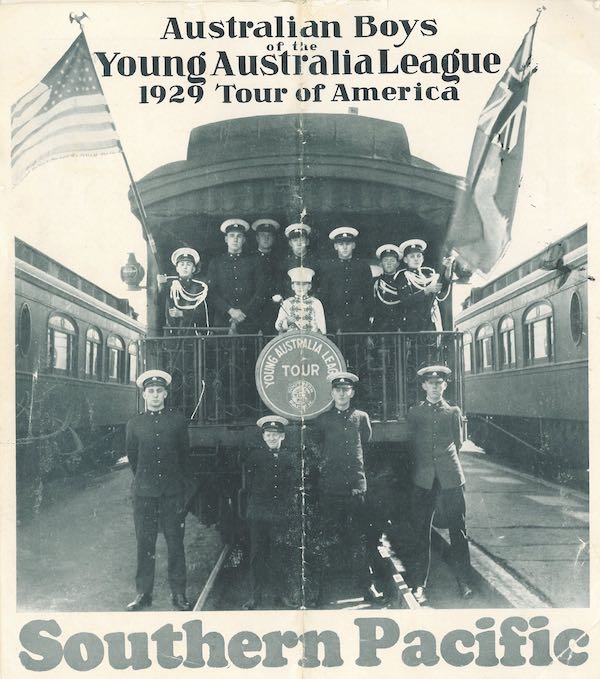

One of the many souvenirs of the YAL's North American tour. Image courtesy Young Australian League Archives 329-035

Education by travel

Central to the Aorangi incident was the Young Australia League (YAL). Founded in Perth in 1905 to foster Australian Rules football, its mission soon changed to encourage sports, music and travel as a means of developing ‘an all-round type of Australian citizen’. Embracing the motto ‘education by travel’, the YAL instigated many interstate and international trips.2

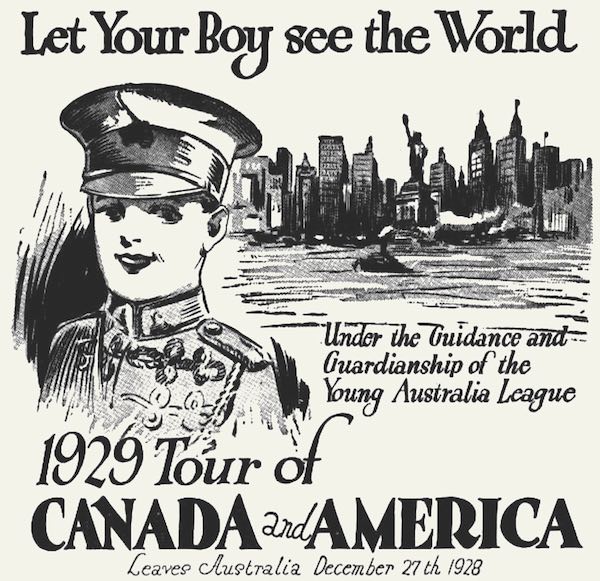

By 1928 a North American tour was planned. Encompassing 43 cities over a six-month period, it would be an unforgettable experience for young men from across Australia. But the privilege did not come cheap – at £195 per head, it cost more than half the annual wage of a manager. Gathering at the Sydney Showgrounds just before Christmas 1928, the party comprised 13 YAL officers, 142 Australian boys and four New Zealand lads. Dressed in military-style uniforms and marching behind ceremonial flags, they paraded through Sydney before boarding the Union Royal Mail Line’s RMS Makura on 27 December.3

Young Australia League tour advertisement, Sydney Sun, 10 September 1928

Frijoles Calientes

On 18 January 1929 the YAL boys looked skyward to the sound of aeroplanes. The aircraft dropped a floral key to the city of San Francisco. It was an auspicious omen: across America and Canada, host families opened their homes to the young men, tours were arranged at local businesses and attractions, and dignitaries greeted the group via an exhausting series of official receptions. The YAL was also given a motley array of souvenirs, including a swathe of flags and three mounted moose heads.

The liveliest memento, however, was bestowed in the desert town of Tucson, Arizona. Arriving on 8 February, the party was treated to ‘enchiladas, tamales, and all manner of Mexican delicacies, the like of which have probably never been seen in Australia’. Local boys Jim and Harry Eager then appeared in cowboy outfits, accompanied by their pet donkey foal, which they presented to the antipodean visitors. ‘The burro now takes its place in all official parades’, noted the tour bulletin, ‘following the band as if trained for the purpose’.4

Christened ‘Frijoles Calientes’ or ‘Hot Beans’, the burro soon became a travelling celebrity. He garnered national exposure in Washington DC, where the YAL joined the inauguration ceremony for Republican President Herbert Hoover. Since his party’s mascot was an elephant, while that of the opposing Democrats was a donkey, ‘nearly a million people rocked with merriment at the sight of the first donkey ever seen at a Republican demonstration’.5 Hoover – who had worked on the Western Australian goldfields in the 1890s – personally greeted each YAL boy and gave the group his inauguration wreath. The only such garland ever to leave the United States, it remains a prized keepsake at the YAL’s Perth headquarters today.

Hot Beans the burro. Image courtesy City of Vancouver Archives

Boss and loss

Managing such a complex operation required an exemplary leader, namely the YAL’s founder, John ‘Jack’ Simons. A nationalist, sportsman, publisher and politician, Simons had irrepressible energy and an imposing force of will. Little wonder he was universally known as ‘Boss’.6

Unfortunately, two tragedies marred the YAL’s American trip. Soon after meeting William Mackenzie King, the Canadian Prime Minister, young Will Strachan of Brisbane suddenly fell ill at Niagara Falls. He died on 19 April from streptococcal pneumonia, aged 17. ‘The young people in our home were very visibly affected upon hearing of this sad occurrence’, commiserated Bert Comins, whose family had recently hosted Will in Boston.7

A second loss occurred on 31 May, just a day after departing Vancouver aboard Aorangi. Suffering a kidney infection, 17-year-old Frank Gilmour from Melbourne died during a series of seizures. His body was committed to the deep, with Captain Robert Crawford reading the burial service.8

Hot Beans had embarked in Vancouver, although his importation into Australia required clearance by the Stock Department. Joining the YAL party on deck as Aorangi slid into Sydney Harbour on 22 June, the celebrated burro was sent to a temporary quarantine paddock beside Taronga Zoo.9

Chickenpox or smallpox?

Welcomed home by 10,000 Sydneysiders, the YAL contingent marched behind 35 souvenir flags to an official reception at Government House. ‘Everywhere you went you were a credit to your country’, proclaimed Dudley de Chair, Governor of New South Wales. ‘Australia is proud of you’.10

But just as the young travellers dispersed, troubling news reached the new Commonwealth Department of Health in Canberra. One YAL boy, Athol Thomas of Perth, had been sent to the Coast Hospital, Sydney’s dedicated infectious diseases hospital. There he was diagnosed with smallpox, a highly infectious disease which, in its severe form, killed up to 30 per cent of patients. The next day William Krimmer from Toowoomba was also found to be suffering from smallpox. Both lads were urgently sent to Sydney’s North Head Quarantine Station.

While abroad, up to 10 YAL boys had been diagnosed with chickenpox, which resembled smallpox but was much milder. Onboard Aorangi, Krimmer also presented with possible chickenpox symptoms, then Thomas fell ill with a similar complaint. Despite being cleared by port doctors in Suva and Auckland, when Aorangi berthed in Sydney the ship’s surgeon, Robert Hatherell, reported both cases as required under maritime law.

After two quarantine doctors inspected the boys, Krimmer was allowed to go home but Thomas was ordered to the Coast Hospital for observation. Only when his case was re-diagnosed as smallpox was it realised that all 491 disembarked passengers – plus several hundred crew – had been circulating in Sydney for days. Since smallpox remained infectious for up to 18 days, the prospect of a snowballing outbreak was palpable.

Aorangi was immediately quarantined and contact tracing urgently commenced. All travellers were urged to report to local quarantine authorities for surveillance. Vaccination against smallpox was recommended but not compulsory, much to the chagrin of the nation’s autocratic Director-General of Health, John Cumpston.11

The Young Australia League delegates return to Perth, 4 July 1929. Image courtesy State Library of Western Australia, 10028B_1320,1462

Acute embarrassment

While the YAL party was at the core of this drama, ‘Boss’ Simons doggedly challenged the health authorities. Escorted by police to North Head, he initially refused to share the addresses of the boys or their hosts. ‘Boss’ also insisted on their right to refuse vaccination, citing a recent tragedy in Bundaberg where contaminated diphtheria immunisation had led to the deaths of 12 children.12

Cumpston complained to the YAL that ‘it is regretted that the provisions of the Quarantine Act do not permit of legal action against Major Simons for his attitude’.13 Equally headstrong, ‘Boss’ urged that Health Department staff ‘refrain from threatening respectable citizens with imprisonment on empty presumptions of resistance’.14

Meanwhile, Commonwealth Health Department staff worked frantically to trace the liner’s passengers and crew. Some proved impossible to locate as they had only given the tour company’s details or supplied false addresses. Others who claimed to have sailed aboard Aorangi could not be found on its manifest.15

To their embarrassment, Commonwealth officials had to admit these failings to state health departments, plus authorities in New Zealand, Canada, the USA and the League of Nations Eastern Bureau in Singapore. It was therefore cheeky, to say the least, when Cumpston proposed that the Commonwealth was responsible only for smallpox cases from Aorangi. The states, he suggested, should foot the bill for infections acquired through contact with the returned travellers.

Hot water and Hot Beans

By early August the crisis had passed. Rob Binney from Perth may have been infected, and two more YAL boys were definitely diagnosed with mild smallpox. In Sydney, John Wright and his family were quarantined at North Head. Rex Halbert, meanwhile, travelled home to Perth before symptoms appeared. His whole family was rapidly transferred to Woodman’s Point Quarantine Station in Fremantle, where his sister Madge developed a mild case. Happily, all the patients soon recovered.

Despite the hot water that ‘Boss’ found himself in, the drama barely dented the positive publicity garnered by the YAL’s North American tour. Cumpston, however, smarted with humiliation. When smallpox was again identified aboard Aorangi in 1930, he ordered that the full quarantine ritual be applied ‘in all details’.16

And what of Hot Beans? Despite a clean bill of health, the burro was landed into zoo custody in Sydney. Under the law he could only be transferred to other zoos, creating a perpetual ‘quarantine’. Despite vigorous campaigning by ‘Boss’, the YAL’s beloved mascot was never released, living out his life at Perth Zoo. For decades afterwards, however, an eternally popular song at YAL concerts was ‘The Donkey Serenade’.

This article appears with thanks to the National Archives of Australia and the Young Australia League.

Header image: RMMS Aorangi off North Head, Sydney, 1939. Samuel J Hood Studio, National Maritime Collection, 00020213

References

1 Bret Walker, Special Commission of Inquiry into the Ruby Princess (Sydney: State of New South Wales, 2020), p 197.

2 ‘The YAL – Tell Me About It’ (Perth: Young Australia League, 1932), pp 1–2.

3 Tour of the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada 1929 (Perth: Young Australia League, 1929), p 3.

4 Ibid, pp 15–16.

5 ‘Mascot’s ill-fortune’, West Australian, 6 February 1930, p 6.

6 Lyall Hunt, ‘Simons, John Joseph (Jack) (1882–1948)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, accessed 1 January 2021.

7 Albert K Comins to Major Simons, 25 April 1929, Young Australia League Archives, folder 586.

8 Aorangi – Official Log Book 10/1/1929 – 22/6/1929 [Box 46], National Archives of Australia (hereafter NAA), Series SP2/1 Control AORANGI 10/1/1929, p 47.

9 ‘YAL boys back from America’, Herald, 22 June 1929, p 3.

10 ‘YAL Boys. Sydney’s welcome. London gift of £1000’, Sydney Morning Herald, 24 June 1929, p 10.

11 J H L Cumpston to Quarantine, Hobart, 25 June 1929, Diseases on Vessels – ‘Aorangi’ Smallpox June 1929, NAA A1928 260/36.

12 Peter Hobbins, ‘“Immunisation is as popular as a death adder”: the Bundaberg tragedy and the politics of medical science in interwar Australia’, Social History of Medicine 24, no 2 (2011): 426–44.

13 J H L Cumpston to Secretary, Young Australia League, 4 July 1929, NAA A1928 260/36.

14 J J Simons to Director-General of Health, 14 September 1929, NAA A1928 260/36.

15 Incoming Passenger List for Aorangi Arriving Sydney 22 June 1929, NAA A907 1929/6/45.

16 Peter Hobbins, Ursula Frederick and Anne Clarke, Stories from the Sandstone: Quarantine Inscriptions from Australia’s Immigrant Past (Crows Nest: Arbon Publishing, 2016), p 235.