The museum had planned 2020 as a year to explore the impact of James Cook’s first Pacific voyage through a sailing program by the Endeavour replica and a suite of exhibitions. Despite COVID cancellations, one of the museum’s current exhibitions seeks to probe the scientific and cultural legacy of the original voyage of 1768–71.

On board Cook's Endeavour 250 years ago was Swedish naturalist Daniel Solander who, with his patron Joseph Banks, became famous as a result of this expedition. Paradise Lost: Daniel Solander’s legacy features artworks that explore his life and achievements and the effects of European contact on the Indigenous peoples encountered on the voyage.

The core of this intimate exhibition, which sees Solander in New Zealand through the eyes of 10 contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand artists, was developed as a response to the 250th anniversary of Endeavour’s historic circumnavigation of New Zealand. Also on display are works from the museum’s collection of 337 copperplate engravings of Australian specimens collected from April to August 1770, published as Banks’ Florilegium and given to the National Maritime Collection by Dr Eric and Mrs Margaret Schiller.

Daniel Solander (1733–82) was a student of the noted naturalist Carl Linnaeus at Uppsala University in the 1750s. He travelled to London in 1760, became engaged in cataloguing natural history collections in the Linnaean system and worked as assistant librarian at the British Museum from 1763. The following year he was appointed a fellow of the Royal Society, where he met the wealthy young amateur naturalist Joseph Banks, with whom he was to form a lifelong friendship and patronage relationship.

In the exhibition, the text for each of the Florilegium engravings notes the various names given to each specimen. Plate 23, shown here, was collected at Bwgcolman, Palm Island, Australia, on 7 June 1770 and carries the Aboriginal name Ya-bu. Solander called it Hibiscus scabrosus, while its modern botanical name, H meraukensis, was attributed by Hochreutiner in 1908. Its common name today is bush hibiscus. It was, unknown to Solander, a vital bush food for the local people. National Maritime Collection 00032545. Reproduced courtesy of Natural History Museum, London and licensed for use by the museum

New lands, new species

Solander subsequently joined Banks’ well-equipped scientific party on James Cook’s Endeavour voyage to the Pacific from 1768 to 1771, along with artists Sydney Parkinson and Alexander Buchan. Their mission was to observe, collect and record plants and animals at sea and on shore, and to observe the customs of local peoples.

On board the ship, Banks and Solander each had a cabin on either side of the commander’s great cabin, which became their shared workspace, as Banks described in 1874:1

… we sat together until it got dark at the great table with our draughtsman directly across from us and showed him the manner in which the drawings should be done and also hastily made descriptions of all the natural history objects while they were fresh. When a long absence from land had exhausted fresh subjects we finished the former description and added synonyms from the books that we had carried along with us.

After Cook’s circumnavigation of New Zealand from October 1769 to March 1770, Endeavour sought the mysterious southern continent then known to Europeans as New Holland. On 29 April 1770 Cook landed at Kamay, a place that he renamed first Stingray Bay and later Botany Bay due to the huge number of plants collected.

By 3 May Banks wrote:2

Our collection of Plants was now grown so immensely large that it was necessary that some extraordinary care should be taken of them least they should spoil in the books. I therefore devoted this day to that business and carried all the drying paper, near 200 Quires of which the larger part was full, ashore and spreading them upon a sail in the sun kept them in this manner exposd (sic) the whole day, often turning them and sometimes turning the Quires in which were plants inside out. By this means they came on board at night in very good condition.

Overall Banks and Solander collected some 17,000 plant specimens, including 350 new species from New Zealand and 900 from Australia.

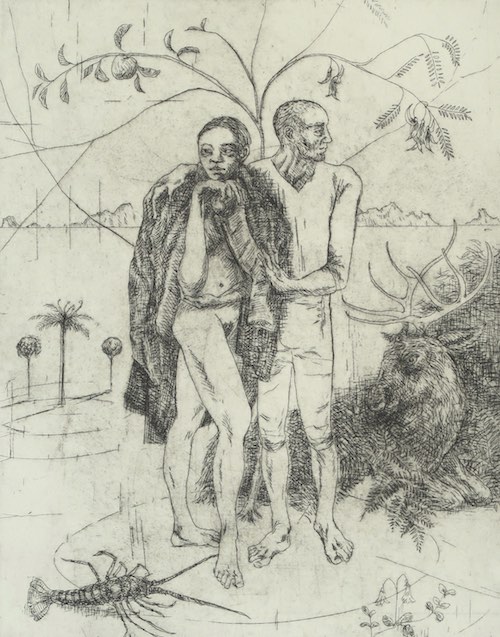

Paradise Lost by Jenna Packer

A mammoth project

When Endeavour returned to England in 1771 both naturalists were widely celebrated. Solander became private secretary to Banks and resumed his post at the British Museum, becoming keeper of the natural history collections in 1773. Famously, Banks was elected president of the Royal Society in 1778, a post he held until his death.

Solander continued cataloguing and describing the Endeavour voyage specimens in preparation for publication. At great expense, Banks engaged five natural history artists and 18 engravers to work from Parkinson’s botanical sketches and the specimens. In 1782 Solander died suddenly, but by that time he had made substantial progress in classifying and describing the Endeavour voyage specimens and the engraved plates were nearly ready. Banks noted:3

The botanical work, with which I am now occupied, is drawing near to its end. Solander’s name will appear on the title page beside mine, since everything was written through our combined labour. While he was alive, hardly a single sentence was written while we were not together.

Between 1771 and 1784 the artists and engravers produced 743 copperplate engravings, but the project was not completed in Banks’s lifetime. After his death in 1820, the plates were bequeathed to the natural history collections at the British Museum, which also held Solander’s manuscript volumes. Today these collections are held in the Natural History Museum.

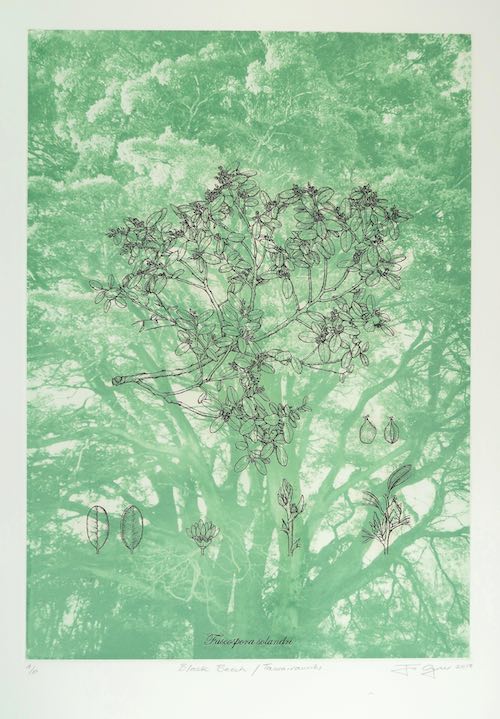

Black beech, Tawairauriki (Fuscospora solandri) by Jo Ogier

Contemporary interpretations

Contemporary artists in this exhibition are Sharnae Beardsley, Dagmar Dyck, Tabatha Forbes, John McLean, Alexis Neal, Jo Ogier, Jenna Packer, John Pusateri, Lynn Taylor and Michel Tuffery MNZM. Each explores different aspects of Solander’s voyage.

Jo Ogier’s etching looks at the legacy of Solander’s collecting and cataloguing in her print Black beech, Tawairauriki (Fuscospora solandri) (2018), one of six New Zealand species named after the botanist.

Dagmar Dyck’s work celebrates her ancestors. Pandanus (Pandanaceae) Fā (2018) represents a cross section of the Fā fibre, a specimen first collected in Tahiti and named Pandanus tectorius by Banks and Solander. Dyck explains:

There is no escaping the way in which pattern is woven throughout the stories of the great Te Moana-nui-a Kiwa [Pacific Ocean]; they are an essential thread in each of our Moana nations’ societal structures … almost every part of the plant is used and within a Tongan context it is known as Fā. Pandanus trees provide materials for all manner of daily uses and are an integral component in the manufacture of Tongan koloa [fibre and textiles].

Jenna Packer has used the exhibition title as a key to explore knowledge systems in her etching Paradise Lost (2018), pointing out that Daniel Solander was striking in his thirst for knowledge. She develops German artist Lucas Cranach’s 16th-century portrayals of Adam and Eve, placing them beneath a Tree of Knowledge that is:

… a hybrid of a European apple tree and Ngutikaka, or kaka beak, which offers the possibility of more than one type of fruit. This tree, however, is also the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, a taxonomic difference which speaks of the cultural values we attach to knowledge.

On the voyage Banks and Solander spent their days botanising, collecting and trying to understand these new plants by comparison with others. And many eluded them. As Dr Edward Duyker has carefully noted, Solander struggled with the unfamiliar eucalypts and the now famous banksia.4

On the other hand, the First Peoples watching the ship had a deep, multi-dimensional knowledge of all plants in their environment. As custodians of the lands, seas and skies, they understood a cosmology to sustain their resources. Their knowledge of seasonal cycles marked hunting, fishing, harvesting and flood or fire seasons. Plants carried different names depending on place, people, language, season and use.

Altogether, the artworks in Paradise Lost shift viewing frames between First Peoples and settler cultures, across knowledge systems, historical time periods, and lines of scientific and cultural inquiry.

Paradise Lost: Daniel Solander’s Legacy is a touring exhibition from the Embassy of Sweden, Canberra, and the Solander Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand. It is showing at the museum until 14 February.

References

[1] Joseph Banks to Johan Alströmer, 16 November 1784, in Edward Duyker, Nature’s Argonaut – Daniel Solander 1733–1782, The Miegunyah Press, MUP, 1998, p 110.

[2] The Endeavour journal of Sir Joseph Banks

[3] Joseph Banks to Johan Alströmer, 16 November 1784, quoted in Duyker, op cit, p 267.

[4] Duyker, op cit, p 181.

[5] Mark Carine, ‘Banks abroad: the botany of the voyages of Joseph Banks'.

This article was originally published in Signals 133.