Investigations continue into the 18th-century shipwreck that lies on the muddy sea-floor of Newport Harbor, Rhode Island. Is it HMB Endeavour? Dr James Hunter, Kieran Hosty and Irini Malliaros provide key insights from the latest fieldwork.

In August and September, maritime archaeologists from the museum and its long-term research partner Silentworld Foundation, joined members of the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project (RIMAP) to continue investigations of an 18th-century shipwreck in Newport Harbor, Rhode Island. This wreck site is a strong contender for Lord Sandwich, a merchant vessel contracted by the government of Great Britain to transport British troops and Hessians (German mercenaries) to North America during the American War of Independence (1775–83).

Lord Sandwich was one of 13 vessels intentionally scuttled by the British in Newport Harbor ahead of a combined land and naval assault on Rhode Island by Continental American and French forces in August 1778, but its significance to Australia is related to its prior identity as HMB Endeavour. Originally called Earl of Pembroke, the former Whitby collier was commanded by Lieutenant James Cook during his first voyage of exploration to the South Pacific between 1768 and 1771.

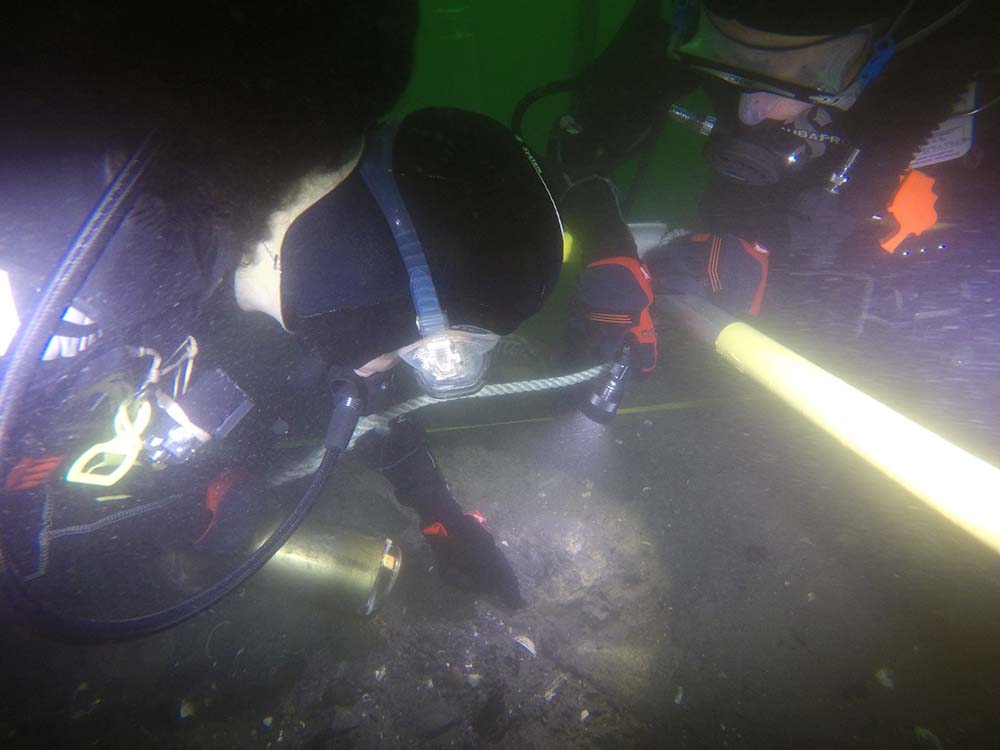

James Hunter illuminates part of RI 2394's excavated hull structure during the 2019 P3DR survey. Image Irini Malliaros/Silentworld Foundation, © RIMAP 2019, used with permission

Promising results … with caveats

In September 2018, the same team conducted archaeological investigations of the visible portions of the shipwreck, collecting scantling measurements from a variety of surviving hull components, sampling selected timbers for species identification, and carrying out a preliminary Photogrammetric 3D Reconstruction (P3DR) survey of the exposed site (see Signals 125). Officially known as RI 2394, the wreck site is largely buried beneath the seabed, but its visible features include stone ballast, four small 18th-century cannons, a lead scupper, and a variety of partially-exposed wooden hull components. Among the hull remains are a line of frames (the floor and first futtock timbers that formed the ‘ribs’ of the ship), as well as sections of hull (external) and ceiling (internal) planking.

Findings from the 2018 investigations suggested RI 2394 could be the remnants of Lord Sandwich/Endeavour. The scantling measurements of most frames matched (or at the very least closely approximated) those listed for Earl of Pembroke, in a survey conducted by the Royal Navy in 1768 before the vessel was accepted into naval service and renamed Endeavour. Timber samples collected from a variety of architectural components throughout the hull were all generally identified as oak (Quercus sp.).

The 1768 Royal Navy survey notes that Earl of Pembroke was constructed with frames and planking hewn from ‘English’ or ‘European’ oak (Quercus robur), a common attribute among British-built ships during the 18th century. Several different species of oak exist however, including some native to North America – such as Southern live oak (Quercus virginiana) – that were also commonly used in shipbuilding during the same period. At least one (and possibly two) of the four vessels scuttled in Newport Harbor alongside Lord Sandwich were American-built, and almost certainly constructed from North American timber species.

Irini Malliaros (left) uses a water-induction dredge to excavate the site, while Kieran Hosty illuminates the work area. Image James Hunter/ANMM, © RIMAP 2019, used with permission

Positive identification of the exact oak species used to construct RI 2394 is absolutely critical to determine whether it was constructed in Great Britain or North America. The prevalence of English oak in the surviving architecture, combined with the right scantlings, would make the wreck a strong contender for Lord Sandwich/Endeavour.

Unfortunately the wood samples collected during last year’s fieldwork were in relatively poor condition, originating from portions of hull timbers that were exposed above the seabed and had suffered damage from marine organisms and other natural processes (such as sediment scouring). Degradation of the cellular structure in each timber sample meant that only very general conclusions could be made regarding their collective identities (for example, each sample was classified as ‘oak’ instead of ‘English oak’). Natural processes also damaged the original surfaces of the exposed timber sections, calling into question the accuracy of their respective scantling measurements.

2019 archaeological investigations of RI 2394

Faced with these issues, the team decided to excavate a small portion of the shipwreck site, aiming to expose deeply-buried and better-preserved sections of hull structure for detailed documentation and timber sampling. We also wanted to determine whether it was outfitted with a ‘rider’ or ‘deadwood’ keelson, which formed part of the vessel’s backbone. The keel is the primary structural component of a wooden sailing ship and extends longitudinally along the bottom-centreline of the hull, while the keelson is a corresponding architectural component that lies atop the floor timbers and locks them against the keel – reinforcing the overall lower-hull structure.

Whitby shipbuilder Thomas Fishburn (who built Earl of Pembroke) was known for constructing sturdy, solid-floored colliers designed to ‘take the ground’ (be run ashore) in shallow tidal estuaries and harbours. To prevent the vessel from breaking its back when taking the ground, Fishburn incorporated a second rider or deadwood keelson into the hull design. This was installed atop the vessel’s regular keelson, substantially increasing its overall height. Unusual and very rare in 18th-century ships, it is known to have been fitted to Earl of Pembroke. As there is no evidence Earl of Pembroke’s additional keelson was altered or removed during its subsequent service as Endeavour and Lord Sandwich, it was one of the hull features we sought during our investigations.

An area encompassing three consecutive frames was chosen for excavation, as these timbers were the most exposed elements of hull structure observed and documented during the 2018 fieldwork. They were relocated at the beginning of 2019, and a steel excavation grid measuring 3 feet (0.91 metres) wide by 9 feet (2.74 metres) long was installed over them and oriented athwartships (across the breadth of the hull). The grid was sub-divided into three separate 3-foot-square sections (nicknamed ‘cells’) that were excavated individually. Alternating 1-foot long yellow and black intervals were marked along the grid’s periphery and provided a visual reference during site mapping and other documentation tasks. Permission to excavate the site was granted by the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission, the state agency responsible for the preservation and protection of Rhode Island’s archaeological sites.

Medium-resolution photogrammetric 3D model of part of RI 2394's excavated hull as it appeared near the conclusion of the 2019 field season. Image James Hunter/ANMM, © RIMAP 2019, used with permission

Using a water-induction dredge, we essentially vacuumed sediment away from the wreck site to expose its hull remains, artefacts and other archaeological features. A mesh bag was attached to the discharge end of the dredge to catch small artefacts (such as miniscule ceramic or glass fragments) that may have been missed by those carrying out the excavation – a very real risk considering Newport Harbor’s poor water clarity during the summer months. A variety of artefacts were recovered during the 2019 field season, including glass bottle fragments, undecorated copper-alloy buttons, animal bones, wooden sheaves (pulleys for running rigging), and part of an articulated wooden barrel. The artefacts are currently undergoing detailed analysis and stabilisation at RIMAP’s conservation facility in Bristol, Rhode Island – work which is partially funded by a museum grant.

A variety of techniques were used to document the site, including P3DR, hand-mapping, and digital still photography and videography. P3DR was used during the 2018 fieldwork, but had its limitations. While it worked well for clearly-defined hull remains and other site components with unique visual attributes, it was insufficient for portions of the wreck that were buried beneath sediment or relatively featureless.

To combat this problem in 2018, we placed photogrammetric ‘targets’ throughout areas of sterile seabed. Each target comprised a small (about 10-centimetre square) sheet of white Mylar, which was printed with a unique geometric pattern to assist the P3DR processing software with combining multiple images into a single digital model. This had mixed results – specific regions within the site were modelled effectively, but the software was unable to generate a composite, high-resolution 3D model of the entire shipwreck.

In 2019 we decided to use more powerful lights capable of cutting through the gloom of Newport Harbor, illuminating an even greater area compared to 2018. Similar to last year, team members pre-programmed their cameras to capture one 12-megapixel image every two seconds, systematically photographing visible elements of the wreck site from multiple perspectives, and ensuring no less than a 60 per cent overlap among captured images. The larger lighting array meant a greater area could be captured within a single photograph, but poor visibility still limited the area of coverage.

Excavation findings

Excavation revealed extensive articulated hull structure, including well-preserved floors and first futtocks, ceiling planking, both of the vessel’s garboard strakes (large exterior hull planks positioned to either side of the keel), and the upper surface of the keel. A large, oval-shaped hole passes through the garboard strake that abuts one side of the keel, and appears to have been created with the intention of scuttling the vessel. It bears hallmarks of having been executed in haste with a heavy striking or cutting implement (such as a crowbar, axe or adze). These include its crude overall form and the presence of impact marks around its periphery – not only to the interior face of the garboard, but also the upper-sided surface of the adjacent keel. Heavy blows to the garboard appear to have worked the wood grain apart and opened a long fissure that is located a short distance outboard of the scuttling hole.

This feature confirms RI 2394 is one of the British transports scuttled during the Battle of Rhode Island, and supports the contention that it could be Lord Sandwich/Endeavour.

Unfortunately, the much sought-after keelson and rider keelson assembly was completely absent, although its outline could still be seen in the form of iron concretion staining on the upper surfaces of the exposed floors. It appears to have fallen victim to biological action and/or other natural processes. Although missing within the excavation footprint, this critical element of the hull’s architecture may be preserved elsewhere on the site.

The surfaces of the buried timbers are pristine, and provided the team with excellent scantling data that is now being compared to archival information related to the design, construction and refit/repair of Earl of Pembroke, Endeavour and Lord Sandwich. Extensive articulated hull structure with significant relief also enabled the team to generate good-quality 3D models of the excavated areas. Medium-resolution models have already been produced, and high-resolution versions are currently in development.

Timber samples were collected from a variety of hull timbers, including floors and futtocks, ceiling planking, one of the garboard strakes, treenails (wooden fasteners used to affix planking to the vessel’s frames), and the keel. Given the issues encountered with the samples collected in 2018, the team made sure to acquire the new batch from timbers that were deeply buried and very well preserved. These have been sent to Australian and American specialists in wood species identification, and results are forthcoming.

In the meantime, members of the team are analysing data retrieved during the 2019 field season, and comparing the information we’ve recovered so far with our historical knowledge of Earl of Pembroke/Endeavour/Lord Sandwich. We’re also scouring archival sources for additional details about the vessel, and are currently planning our next round of fieldwork in January 2020 when the near-freezing but much clearer waters of Newport Harbor are more conducive for underwater photography. Stay tuned!

Further Reading

Abbass, D K, 2001, ‘Newport and Captain Cook’s ships’, The Great Circle, Vol 23 No 1, pp 3-20.

Connell, Mike and Liddy, Des, 1997, ‘Cook’s Endeavour bark: Did this vessel end its days in Newport, Rhode Island?’, The Great Circle, Vol 19 No 1, pp 40-49.

Erskine, Nigel, 2017, ‘The Endeavour after James Cook: The forgotten years, 1771-1778’, The Great Circle, Vol 39 No 1, pp 55-88.

Hunter, James, Hosty, Kieran and Malliaros, Irini, 2018, ‘Piecing together a puzzle: Photogrammetric recording in the search for Cook’s Endeavour’, Signals 125, pp 14-19.

Knight, C., 1933, ‘H.M. Bark Endeavour’. The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol 19 No 3, pp 292-302.

Marquardt K H, 1995, Captain Cook’s Endeavour: Anatomy of the Ship, Conway Maritime Press, London.

McGowan, A P, 1979, ‘Captain Cook’s ships’, The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol 65 No 2, pp 109-118.

This article originally appeared in Signals magazine (issue 129)

Header image: A well-preserved wooden sheave (pulley) uncovered during the 2019 excavation. Image John Cassese/RIMAP 2019, used with permission