Science of the sea, at sea

Australia is surrounded by deep, mysterious oceans.The RV Investigator is Australia's dedicated bluewater research vessel, and it is tasked with exploring these depths. Managed by the Marine National Facility Investigator is equipped to monitor our fisheries, learn more about weather patterns and large ocean processes, undertake deep sea oceanography as well as map the geography of Australia's marine estate. It can deliver 300 research days a year, for up 60 days at a time and can carry a team of 40 scientists on board.

RV Investigator. Image: CSIRO/Marine National Facility.

But who is conducting this groundbreaking science on board? Enter Dr Joanne (Jo) Whittaker, marine geophysicist, and Dr Rebecca Carey, volcanologist. Together they are gathering data to unlock the ancient history of Zealandia and gathering information about the seabed between Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica.

Underwater volcanoes

You probably didn’t know that submarine volcanism accounts for around 75% of the world’s volcanic activity – and most of it is so deep it doesn’t have any physical manifestation on the ocean’s surface. This plays an important role in ocean temperature and the circulation or convection of water in ocean basins, which also provide essential energy and food for ocean biodiversity.

In Australia, our submarine volcanoes are largely extinct but contain lots of mineral deposits such as lead, copper, gold and silver.

Submarine volcanism accounts for around 75% of the world’s volcanic activity – and most of it is so deep it doesn’t have any physical manifestation on the ocean’s surface.

“In the past, most research on volcanic activity was conducted with volcanoes on land. These were the easiest to study! Field studies were conducted to get observations, measurements and data, which in turn we used to create accurate models to simulate volcanic activity,” explains Jo. “But there is so much we don’t know about underwater volcanoes and the role they play in climate regulation. We need data to create the models of how these volcanoes operate on Earth.”

Her work with Rebecca is essentially trying to piece together a 200-million-year jigsaw puzzle to understand the fundamental processes which drive plate tectonics. She’s asking questions to determine where plates were, why and how they moved, and what is happening now.

To this end, last December they boarded Investigator and journeyed to the Tasman Sea to study the role of the Balleny mantle plume, a hotspot of underwater volcanic activity. The Balleny plume is an upwelling of magma from the Earth's interior through the mantle. It is believed to have been responsible for the formation of many volcanic seamounts off the east coast of Tasmania.

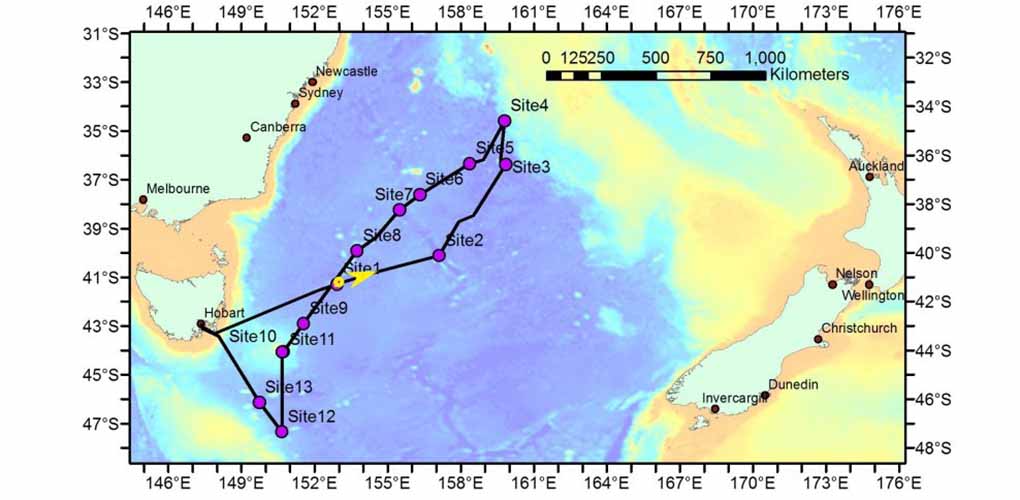

Joanne and Rebecca's research is seeking to better understand this chain of seamounts that stretches across the Tasman Sea. Image: MNF/CSIRO.

Zealandia, seamounts and how Antarctica may have gotten its climate...

So what caused that extensive oceanic continental crust which extends north and south of New Zealand? A lost continent, one Rebecca and Joanne call ‘Zealandia’. This voyage gathered data to test the hypothesis that the Balleny plume is linked to the continental breakup between Tasmania (Australia) and Cape Adare (Antarctica) 30-50 million years ago.

Seamounts are formed by plumes of super-heated material spilling up from the earth’s mantle and crust. The Australian tectonic plate then moves over the top of these plumes, causing a progressive string of volcanoes.

“Lord Howe Island is an example of a what these seamounts could have looked like millions of years ago. It’s an eroded volcano that’s about 7 million years old. We knew the seamounts were there but had never known their age, what they were made of, never had any samples,” continues Jo. “We’re investigating what role these processes might have played in the breakup between Australia and Antarctica.”

“We theorize that this process is part of the reason why Antarctica became so cold. The opening of this tectonic gateway, the movement of these continents and the creation of these seamounts affected the circumpolar current. The water got separated, deeper and colder. It developed its own strong current, leading to Antarctica developed it’s unique climate,” says Rebecca.

But this work also has out-of-this-world applications: “We’re also working on models to simulate what volcanic activity might look like on Mars or Io, which involves tweaking the maths in the models to correspond with what we know about the climate, geography and atmosphere of these places. This means we need more data about volcanoes here on earth, especially all those volcanoes hidden under the waves. This requires us to spend a lot of time in the field. Up to nine months a year.”

Collecting the data

Scientists collect, study and analyse rocks from the seamount chain stretching across the Tasman Sea, and gather geophysical data about the seafloor. This is used to examine the geology, history and origin of the seamounts. Geological samples are collected using rock dredges and Smith Mac Grab (a rock scoop). Seafloor and subseafloor geophysical data will be collected using the ship’s multibeam sonar, sub-bottom profiler and gravity meter.

Rebecca explained the slow process of collecting rock samples: “You speak with the Captain about potential targets to dredge for samples. You need cooperative weather and hope that the net doesn’t get snagged (it can take hours to unsnag). Each dredge takes around four to five hours. The wire of the bucket can be deployed up at a rate of up of 60 metres a minute, and you are dredging locations often kilometres below the surface, for up to an hour each pass.”

“When you first empty the dredging bucket, it is often hard to tell if any of the rocks are what you need. You often can’t tell what the rocks are. So you have to break them apart to do a spot check. We found an unusual sample last time: a whale ear bone!”

"We found an unusual sample last time: a whale ear bone!"

Then it’s off to the lab on board, where the team clean, catalogue, describe, photograph and label the samples. Around 12 scientists in the lab, six people per shift. Sometimes school teachers on board under the CSIRO Educator on Board program have a go too.

Doctor Joanne Whittaker inspects samples from a dredge, January 2019. Image: MNF/CSIRO.

Life on board the Investigator is regimented. You work in 12 hour shifts, from 2am-2pm or 2pm-2am. The Galley is always open with cereal and bread, tea and coffee. But there aren’t hot meals if you have a 2am start.

“Investigator a fantastic ship. It’s so well equipped. But it is surprisingly hard to wash your hair, due to the movement of the ship and the size of the showers. The best tip: wedge yourself into the corner of shower to get stable enough to finish washing the shampoo out,” chuckles Jo.

"But it is surprisingly hard to wash your hair, due to the movement of the ship and the size of the showers. The best tip: wedge yourself into the corner of shower to get stable..."

Future research

On 7 January, while still out in the middle of the Tasman Sea, Jo and Rebecca gave the museum a call. This ‘live link’ from Investigator to the museum connected scientists to visitors and enabled them to ask questions of the scientists and staff on board. We got a chat with the Chief Scientists, a tour of the vessel and even got to see rock samples split on deck.

Now the team are preparing for another voyage this August to the Coral Sea. This time they will explore the Louisade Plateau and study hotspots dynamics. Who knows what they might dig up...

If you want to see the science first-hand and follow the voyages of Investigator, visit the 24/7 ship livestream.

This research was supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.