A twist of fate

Jim Stone’s journey to Australia as a British child migrant was determined by a twist of fate during the Second World War. Shortly before the outbreak of conflict in 1939, the three-year-old and his five-year-old sister Marjory were taken into the care of Dr Barnardo’s Homes in Liverpool, England. Their single mother, Johanna Riding, did not have the means to support two growing children from her meagre income as a hostel worker in the seaside town of Hoylake in Merseyside. When she met and married a widower 20 years her senior, she did not dare to reveal to him that she had two illegitimate children. In the days before the modern welfare state, Johanna had little choice but to hand them over to Barnardo’s, a charity that had been providing residential care to vulnerable children since the late 1860s. Jim and Marjory never saw their mother again.

In 1943 Jim and his sister, like many children from Britain’s war-ravaged cities, were evacuated to the safety of the countryside, where they were placed on separate farms in Tamworth, Staffordshire. It was here, in 1945, that Jim received a severe beating from his foster parent. Fatefully, the very next day, he was visited by the district nurse for a routine medical inspection. When the nurse found the welts on his back, Jim was immediately removed from Tamworth, and consequently from his sister. He was sent to the Barnardo’s home at Stepney Causeway in London’s East End, and then the Dalziel of Wooler Memorial Home at Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, setting in motion a series of events that would culminate in his migration to Australia with Barnardo’s after World War II.

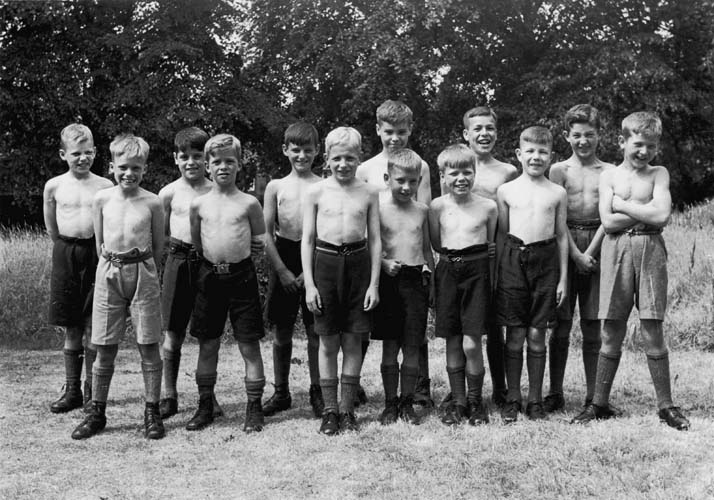

Jim Stone (third from left) with Barnardo boys at Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, UK, c 1945–1947. Reproduced courtesy Jim Stone.

Jim’s lasting memory of Kingston was the cold weather, and the rough wool shirts the boys had to wear during the long, miserable winter. It chanced one winter’s day that they were visited by a group of officials looking for boys to emigrate to Canada or Australia. Although Jim had little knowledge of either country, he was aware that Canada was as cold as England, while Australia was significantly warmer. He promptly made his decision and raised his hand for Australia.

From the late 19th century, the mass migration of unaccompanied children from overcrowded orphanages, institutions and children’s homes became part of a broader strategy to consolidate the growing British Empire with "good British stock".

From the late 19th century, the mass migration of unaccompanied children from overcrowded orphanages, institutions and children’s homes became part of a broader strategy to consolidate the growing British Empire with ‘good British stock’. The Australian Government actively pursued these child migration schemes throughout the 20th century as part of its ‘White Australia’ policy and later its postwar mandate to ‘populate or perish’, accepting more than 7,000 children through various philanthropic and religious organisations (including approximately 2,800 from Barnardo’s).

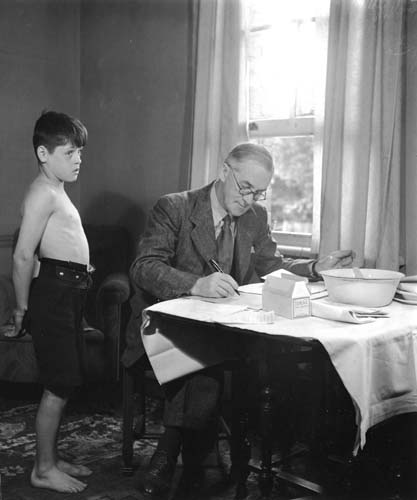

Jim Stone undergoing a medical examination in the UK prior to his selection for Australia, c 1946. Reproduced courtesy Jim Stone.

Children were required to be physically and mentally fit to be approved for emigration. Jim remembers undergoing several medical examinations over a period of 12 months, before becoming one of five boys selected from the Kingston home. In October 1947 they joined a group of child migrants at Thurlby House in Woodford Bridge, Essex, to prepare for departure. While there Jim was visited by his ‘auntie’ Connie, a corporal in the Auxiliary Territorial Service (the women’s branch of the British Army) who had befriended him and taken him on outings to Nottingham Castle, Sherwood Forest and the Kent coast. Connie tried to persuade Jim to change his mind about Australia but, at the age of 11, he was adamant about his decision. Many years later Jim discovered that she had wanted to adopt him, but was unable to because she was not married.

Jim Stone and his ‘auntie’ Connie at Thurlby House in Woodford Bridge, Essex, UK, 1947. Reproduced courtesy Jim Stone.

On 10 October Jim and the other boys, dressed in suits, shirts and ties, travelled by bus to London’s Tilbury Docks, where they embarked on SS Ormonde for their six-week voyage to the other side of the world. The ship was farewelled by a brass band and many publicity photographs were taken of the group, as they were the first Barnardo’s child migrants to depart after the war, and thus of great political and media interest in Britain and Australia.

Jim Stone (sixth from right, holding parcel of cakes) on departure from Thurlby House in Woodford Bridge, Essex, UK, 1947. Reproduced courtesy Jim Stone.

Ormonde passed through Port Said, the Suez Canal and Aden, but the children were not allowed ashore because of a cholera epidemic. In Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), they were received by dignitaries and treated to lunch and musical entertainment at a grand hotel. While the heat was unbearable for some, Jim relished it and looked forward to their arrival in Fremantle, waking before dawn to wait on deck for his first glimpse of Australia. The children were feted at each Australian port of call, with a reception from the Lord Mayor of Perth and a picnic on the banks of the Swan River, another mayoral reception and picnic on Mount Lofty in Adelaide, and a visit to a large department store in Melbourne.

On 18 November the group disembarked in Sydney and attended a wharf side reception with numerous speeches, before finally boarding a bus for the Dr Barnardo’s Farm School, Mowbray Park, at rural Picton, south of Sydney. This marked the beginning of what Jim describes as a period of incarceration. The smart clothes with which he and the other boys arrived were removed and sent back to Britain for use by the next party of child migrants. They were issued with khaki shirts and shorts and would go barefoot, even in the winter, wearing shoes only on Sundays for church.

Opened in 1929, Mowbray Park was a farm training school for children aged six to 15, who lived in small cottages under the care of a cottage mother. Discipline was strictly enforced and the day began early. Jim recalls that the boys would assemble at 5.45am for exercises, before returning to their cottages to make their beds, eat breakfast and prepare for school.

The farm school was self-sufficient, with 200 chickens, 70 dairy cows and half a dozen Clydesdale draught horses for land clearing, ploughing and transporting milk. The children grew their own fruits and vegetables and also supplied them to the Dr Barnardo’s Girls’ Home in the Sydney suburb of Burwood, where girls were trained in domestic skills such as cooking and cleaning. The farm had no refrigeration, and during the summer months, ice was obtained from an ice works some five kilometres away. Jim remembers loading a horse and cart with blocks of ice about one metre in length, which would be diminished to half their size by the time they reached the farm several hours later. This problem was overcome once the school acquired a small Massey Ferguson tractor, reducing the trip to a third of its previous duration.

When they turned 16, children would spend six months as farm trainees, before being sent to remote agricultural regions to become farm labourers. Jim and another student were permitted to remain at school until the age of 17 as they had shown an aptitude for learning and were encouraged to complete the Leaving Certificate. Jim left Mowbray Park in 1953 and spent two weeks on a sheep station in the Wagga Wagga district, where he assisted the grazier with crutching of the ewes (shearing wool from around the tail and between the hind legs) prior to lambing. This experience spurred his interest in grading and classifying wool and led to his first job as a wool classer at Grazcos in Alexandria, Sydney. In 1957 he became a roustabout (shearing shed hand) for a contractor near Nyngan in central western New South Wales, to learn wool classing in the sheds.

In 1960, with the economy moving into recession, Jim decided it was time for a career change and studied at night to become a chartered accountant. He and his partner Josie relocated to New Zealand, where they later married and lived for 32 years, with Jim operating an accounting practice in the small town of Taumarunui on the North Island. He then worked as a senior investigating accountant and senior technical officer with the Inland Revenue Department in Auckland, while also farming green-lipped mussels in partnership with two friends. After his wife passed away in 1998, Jim returned to the country he loved, retiring to Yamba at the mouth of the Clarence River in northern NSW. He was attracted by the warm climate of the region, and the enduring memory of a childhood visit to the Bellingen dairy farm once owned by the son of the superintendent at Barnardo’s Mowbray Park.

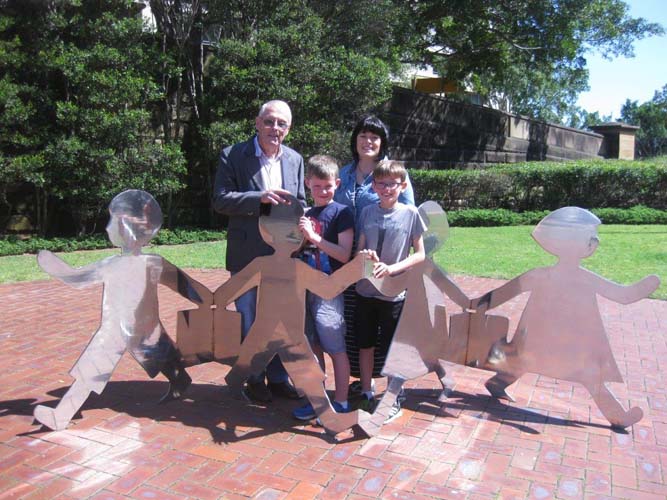

Jim has often contemplated how his life might have turned out had he not become a ward of Barnardo’s in wartime Britain, and believes that his chances of success or even survival would have been poor. He says, ‘When I reflect on my past, I cannot help but hold the view that I have been blessed by chance, good fortune and a certain amount of luck. There is not much in my life that I regret having done. If I had to go over my life again, then I imagine I would be happy to repeat it.’ Jim’s daughter Penelope registered his name on the Welcome Wall as a proud and tangible reminder of the Barnardo boy from Liverpool for his two grandsons, Ryan and Liam, and future great-grandchildren.

Jim Stone, his daughter Penelope and grandsons Liam and Ryan at the Sydney memorial to British child migrants, Coming and Going, at the ANMM, 2015. Photographer Kim Tao/ANMM.

This article originally appeared in Signals Magazine (Issue #113).