This week marks 30 years since an aspirational nation woke up to news that Australia had licked the Americans in a blue-blood yachting event, finally wresting the coveted America’s Cup from the nation which had held it for 132 years and fought off all challengers including long-standing Trans-Atlantic rivals England, Scotland, Ireland, Canada to its northern border and across the Pacific to Australia.

Australia II and Liberty racing in 1983. Photographer: Sally Samins. Reproduced courtesy the photographer. ANMM Collection Gift from Sally Samins

With the series tied at three races each, many Australians had stayed up all night to watch the cliff-hanger on television. The last race saw skipper John Bertrand lead his crew in Australia II in a tacking duel, crossing the line 41 seconds ahead of veteran skipper Dennis Conner in Liberty.

A sporting triumph, Australia II’s success was amplified in lounge rooms across the country in the early morning of 26 September 1983 when our sports-mad Western Australia–born, former trade unionist, consensus politician Prime Minister Bob Hawke celebrated with the crowd at the Royal Perth Yacht Club. Clad in a jacket emblazoned with maps of Australia, splashed in champagne from revellers, the ebullient, tee-totalling Prime Minister unofficially declared the day a national holiday exclaiming that;

“any boss who sacks someone for not turning up is a bum”.

Australia, the victors, celebrated to the jingoistic yet catchy vocals of Australian band Men at Work’s anthem We come from a Land Down under, embracing their green and gold boxing Kangaroo battle flag. And the syndicate’s secret weapon, the winged keel, was dramatically unveiled in the chaos dockside after that final race.

Australia II’s keel shrouded at Newport during the 1983 cup challenge. Photographer: Sally Samins. Reproduced courtesy the photographer. ANMM Collection Gift from Sally Samins

The New York Yacht Club was bruised from the arduous campaign of its own rule challenges, protests, claims, counter claims, and extreme frustration at the secrecy and theatre surrounding Australia II’s ‘upside-down’ keel. Shrouded dockside with its security guard, hasty design adaptations included the addition of endplates on the keel of one of its boats. It licked its wounds, and unbolted the extravagant silver Cup from its high security case.

|

Newspaper front pages from the 1983 America’s Cup. ANMM Collection. Gift from Bruce Stannard |

Newspaper front pages from the 1983 America’s Cup. ANMM Collection. Gift from Bruce Stannard |

Known as the Mount Everest of yachting, the America’s Cup was perceived as unwinnable. America’s stranglehold on the race was widely believed to be the result of the host’s privilege to define, protect or control rules and regulations. No challenge had succeeded since the race, held every three years, was first contested in 1851.

The battle flag, anthem and drama of the Australian campaign were overt symbols of the brash character of the Australian challenge and its participants.

Celebratory press conference with Australia’s protagonists (left to right) unknown, unknown, John Bertrand, Alan Bond, and Warren Jones. Photographer: Sally Samins. Reproduced courtesy the photographer. ANMM Collection Gift from Sally Samins

It was a Western Australian campaign bankrolled by entrepreneur, ‘ten pound pom’ Alan Bond and orchestrated with great finesse by syndicate brain Warren Jones, in a 12-metre class yacht designed by the brilliant, self-taught former sailmaker Ben Lexcen, with its crew skippered by exciting sailor John Bertrand. All proved equal and eventually superior in their respective fields to the experience, athleticism and guile of the American syndicate.

The brashness of the Australian challengers was looked upon with distaste by the New York Yacht Club. Australians had been challenging for the Cup for a generation, and had thought about it back in the 1880s when naval architect Walter Reeks visited the States. Australia had won the right to challenge every three years bar one since 1962 when Sydney media baron and sailor Sir Frank Packer bankrolled the Alan Payne designed Gretel to scare the Americans a little with its efficient winch system, deck layout and speed to windward. With six further challenges moving from the east to the west coast of Australia the two countries had enjoyed a twenty year rivalry. Yet the sheer theatre of this new Western Australian challenge trumped American respect for that long-standing sailing rivalry.

The rivalry continued – souvenirs from 1987. ANMM Collection

When looking back to the origins of the race in 1851 Australia II’s win resonates. Losing to the young upstarts in Australia, although a disaster for the New York Yacht Club establishment, was possibly a fitting way for the longest winning streak in competitive sport to end for America.

In 1851 in the midst of the industrial revolution, on the cusp of London’s International Exhibition, a syndicate of industrialists marshalled behind that very first race, answering an invitation from its former colonial master and yachting powerhouse to send one of the famously competitive New York pilot boats to challenge the British yachts.

Sheet music composed for Commodore John C. Stevens, featuring the schooner America after its victory in 1851. ANMM Collection

Seizing the commercial opportunity the Yankee Syndicate commissioned a radical pilot-boat-style schooner with sharp bow and raked masts, patriotically named it America and spared no expense on its fitout. They travelled to challenge yachts from the Royal Yacht Squadron under the auspices of the fledgling New York Yacht Club, founded in 1844. The rest of the story is history.

After an unsuccessful protest about the challenger’s course at Cowes, America trounced its rivals and won that Hundred Guinea Cup. Its win and England’s loss created a sensation, sparking rumours of cheating, yet it prevailed. The schooner America became one of the most famous yachts to date.

Back in New York and after the upheaval of the American civil war, the elaborate silver cup was drafted as the symbol of a challenge race between nations and named the America’s Cup. It became more potent and more redolent of American dominance as successive challengers came and went over more than a century.

Australia II’s win after 132 years was similarly startling, although the winning streak was less enduring. It created shock waves in yachting circles in design innovation and in nationality rules stipulating that the design, construction and crews had to come from campaigning countries.

|

1987 America’s Cup challenger Stars and Stripes’ test tank model arriving at the museum. Stars and Stripes won the cup back from America. ANMM Collection. Gift from San Diego Yacht Club |

1987 America’s Cup challenger Stars and Stripes’ test tank model arriving at the museum. Stars and Stripes won the cup back from America. ANMM Collection. Gift from San Diego Yacht Club |

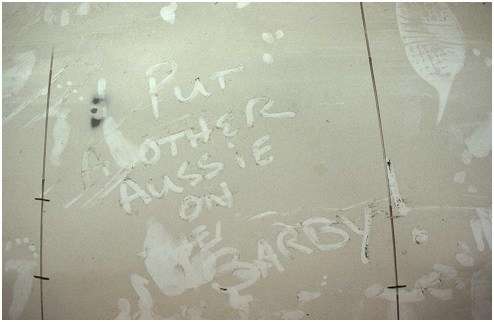

Inscribed in dust “Put another Aussie on the barby”. Stars and Stripes won the cup back from America. ANMM Collection. Gift from San Diego Yacht Club

The Cup travelled to the Perth suburb of Dalkeith on the Swan River at the Royal Perth Yacht Club, as a prelude to time in subsequent winning countries New Zealand, Switzerland and the Golden Gate Yacht Club in San Francisco which it will soon leave after last week’s win by Team New Zealand.

Today the racing craft are unrecognisable from the conventional graceful displacement monohulls, the result of a spiral of design innovation after Lexcen’s winged keel. Finely-tuned machines, they are super-fast, febrile, 22 metre (72 foot) long catamarans which skim above the water, touching it only at three points, by small fins. With helmet-clad crews rushing across the trampoline like spiders, these incredible craft are powered by solid winged sails. They are also highly expensive and dangerous.

Country–of-origin rules too have been relaxed and now the race, always characterised by the pirate’s treasure chest directed to the boats, appears solely governed by money. All necessary expertise to attain the fastest craft, the slickest campaign and the best crew is bought in from around the world.

When the all-Australian crew steered their Fremantle-built yacht Australia II to victory in 1983, the syndicate had to defend accusations that the design was not all Australian, all Ben Lexcen.

From 1981 Lexcen had trialled his hull and keel design at a tank testing facility at Wageninin in the Netherlands with five 1/3 scale models. The American syndicate charged that it was therefore not an Australian design. At the time the Netherlands ship model basin naval architect Peter van Oosanen countered that it was Lexcen’s design and the case was settled.

More than 25 years later though, Oosanen asserted that he was involved in the design innovation. Yet if you look back to Ben Lexcen’s early skiff designs, especially his radical 18-footer Taipan built in 1959, you can see that the creative spark was certainly Lexcen’s. Taipan features endplates on its rudder and centreboard revealing his experimentation to reduce drag.

Today, crews are drawn from sailing nations around the world. Oracle, the recent unsuccessful American defender was skippered by an Australian with only one American in the crew.

The high-speed catamaran racing of today’s America’s Cup too is seduced by its new-found popularity. With 20 minute races, extravagant boats and gymnastic crews, the event is more a spectator sport than ever before. More than 50,000 people are reported to have lined the docks on San Francisco Bay the past few weeks. Although discussions are being held about making the catamarans less-expensive when the America’s Cup moves to New Zealand, organisers are reluctant to relinquish the fame the new America’s Cup boats have brought to the event. We’ll wait and see.