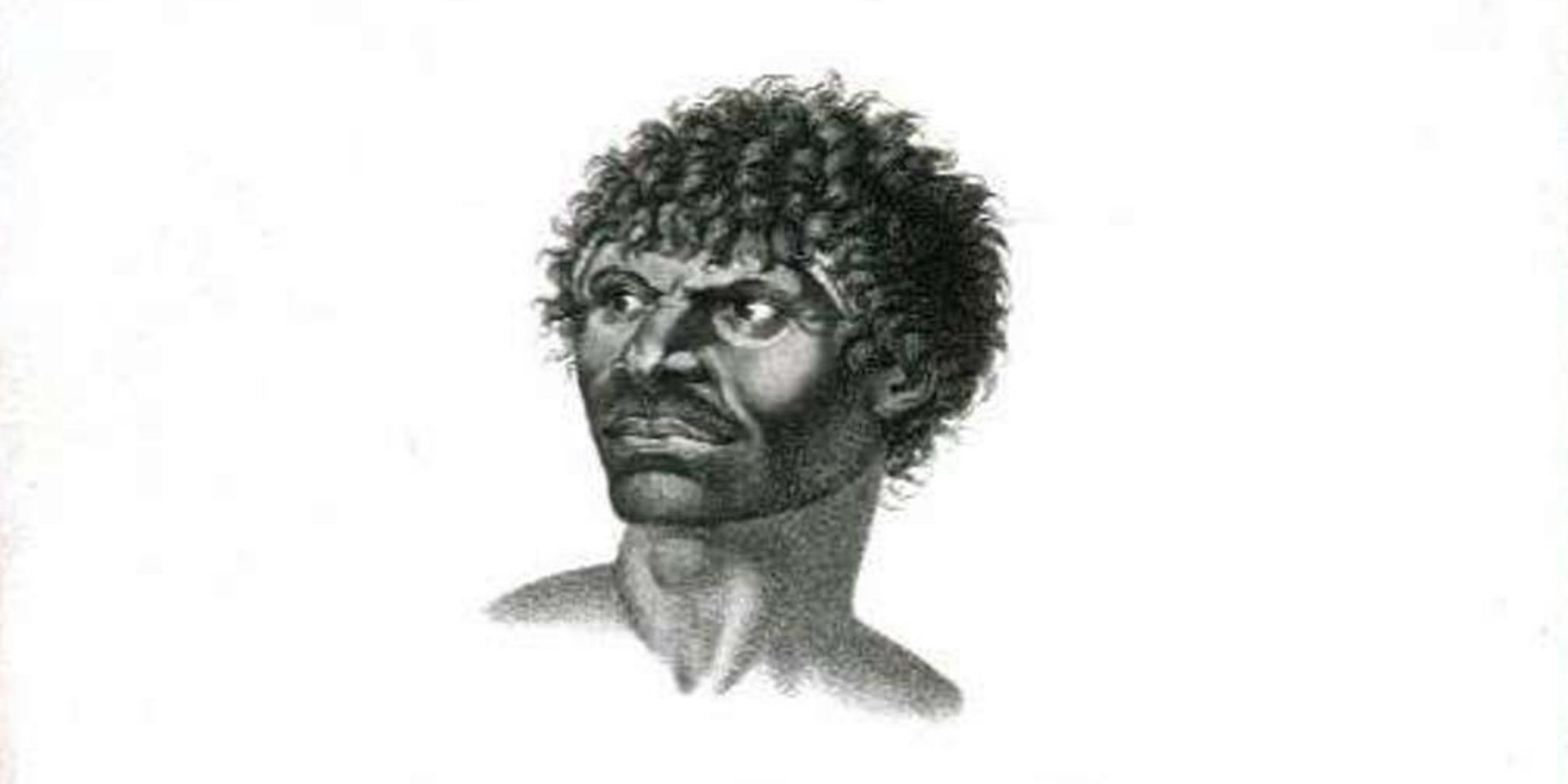

Engraving of Gnung-a Gnung-a by Nicolas-Martin Petit in 1807

You may have heard of Bennelong, the famous Aboriginal man who befriended Governor Arthur Phillip and accompanied him to England in 1792. Fewer people, however, have heard of Gnung-a Gnung-a Mur-re-mur-gan, who became the first Aboriginal Australian in written history to visit America in 1793. His story has been reconstructed from written records from Judge-Advocate David Collins whose work, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, provides snippets of information about the voyage of HMS Daedalus across the North Pacific to America.

According to the records, Gnung-a Gnung-a was sent by Lieutenant-Governor Major Francis Grose to sail on the expedition, ‘for the purpose of acquiring our language.’ Lieutenant Hanson was instructed to ‘by no means’ ‘leave him at Nookta, but, if he survived the voyage, to bring him back safe to his friends and countrymen.’ Collins described his own insights regarding Gnung-a Gnung-a’s character, claiming that, ‘he was a man of a more gentle disposition than most of his associates’ and willingly accepted the voyage. On the 1 July 1793, Gnung-a Gnung-a boarded HMS Daedalus, leaving behind his young pregnant wife Warreeweer, sister of Bennelong, ‘of whom he always appeared extremely fond’.

Although not much is reported about Gnung-a Gnung-a’s time on the voyage, there are some intriguing accounts of his visit to Hawaii. Collins describes the high esteem Gnung-a Gnung-a held amongst his sailing companions as he ‘conducted himself with the greatest propriety…readily complying with whatever was required of him.’ During Gnung-a Gnung-a’s stay, the Hawaiian King Kamehameha offered to purchase him, ‘making splendid offers to Mr. Hanson, of canoes, warlike instruments, and other curiosities….’ Gnung-a Gnung-a refused the offer as he was anxious to return to New South Wales.

A few months later, on 3 April 1794, HMS Daedalus returned to Port Jackson. Gnung-a Gnung-a disembarked, appearing in ‘English dress, and very clean’, to find a large reception of his people waiting to greet him. Amongst the crowd was his wife, who was ‘in the possession of another native, a very fine young fellow, who since his coming among us had gone by the name of Wyatt.’ Collins dramatically captures the moments after their encounter:

‘The husband and the gallant eyed each other with indignant sullenness, while the poor wife (who had recently been delivered of a female child) appeared terrified, and as if she knew not which to cling to as her protector, but expecting that she should be the sufferer, whether ascertained to belong to her former or present master.’

Gnung-a Gnung-a performed ritual revenge by throwing a spear and wounding his rival. He emerged the victor with Warreeweer claimed as the ‘prize’, despite later reports of Gnung-a Gnung-a being ‘seen traversing the country in search of another wife.’

In December 1795, another ritual revenge battle is recorded to have taken place in Sydney between Gnung-a Gnung-a and the great warrior and leader of the Bidjigal people, Pemulwuy. According to Collins, Gnung-a Gnung-a received a barbed spear in ‘his loins close by the vertebrae of the back’. English surgeons later declared that they could not dislodge the spear and so Gnung-a Gnung-a, ‘determined to trust to nature’, left the hospital and was seen for ‘several weeks’ after ‘walking about with the spear unmoved’. Further to these accounts, Collins claims that Warreeweer ‘had fixed her teeth in the wound and drawn it out’. Although Gnung-a Gnung-a recovered, ‘which gave general satisfaction, as he was much esteemed by every white man who knew him…for his personal bravery’, the incident left him with an injury which plagued him for the rest of his life.

View of Sydney from Bennelong Point, as it would have appeared in Gnung-a Gnung-a's time

On 12 January 1809, Gnung-a Gnung-a was found dead behind the Dry Store (present day Sirius Park in Bridge Street, Sydney). The exact cause of his death is unknown, however, the Sydney Gazette described Gnung-a Gnung-a, referring to the injuries inflicted by Pemulwuy years earlier and his general character:

‘The deceased was to us well known, for his lameness…He was not less remarkable however for the docility of his temper, and the high estimation in which he was universally held among the native tribes:- he had extended to many an orphan a fostering hand, and, as his own children, provided for their infant wants….’

Apart from a small number of written accounts, all that survives of Gnung-a Gnung-a is a coloured drawing attributed to convict artist Thomas Watling and the engraving featured here, which was created by French artist Nicolas-Martin Petit in Sydney in 1802. From the little information we can gain from these accounts, what emerges is a fascinating story of dramatic encounters and adventure. Gnung-a Gnung-a’s story and Collins’ observations shed light on relations between Aboriginal Australians and Europeans at such a crucial moment in Australia’s colonial history. These stories bring Petit’s portrait to life in a way that demonstrates how prominent Gnung-a Gnung-a was during the period of early settlement – a figure held in high regard by both Aboriginal Australians and Europeans alike.

NC